Column: Mass shooters seek notoriety, and we, the media, provide it. Is there another way?

- Share via

Tom Teves has told the story of losing his son Alex in an Aurora, Colo., movie theater so many times over the last seven years that the details come automatically.

His son Alex was in the third-to-last row. Techno music blasted in the shooter’s headphones to hide the screams of the injured. It was July 20, 2012, and Alex was sitting next to the woman he had already told his parents that he planned to marry.

Teves wishes he could stop talking about it. It’s a story about grandchildren he never got to hold and memories he never got to make, with no happy ending or healing or lessons to share.

And at the end of the retelling, what he’s left with is another year to pass without Alex, who was 24 when he died, studying to be a counselor. He says it’s like a 100-pound weight he carries everywhere he goes. He can get better at lifting it, but the load never gets lighter.

“People want to hear puppies and kittens and silver linings,” Teves said. “But there’s no silver lining to our story. Alex is dead. For the rest of his life, and for the rest of our life.”

But every time a mass shooting is in the news — as in recent weeks when shooters attacked the Gilroy Garlic Festival, a Walmart in El Paso and a nightlife area in Dayton, Ohio, and left more than 30 dead — he tells the story as many times as he can stand.

“It’s too late for my son,” he said. “The goal now is to save someone else’s.”

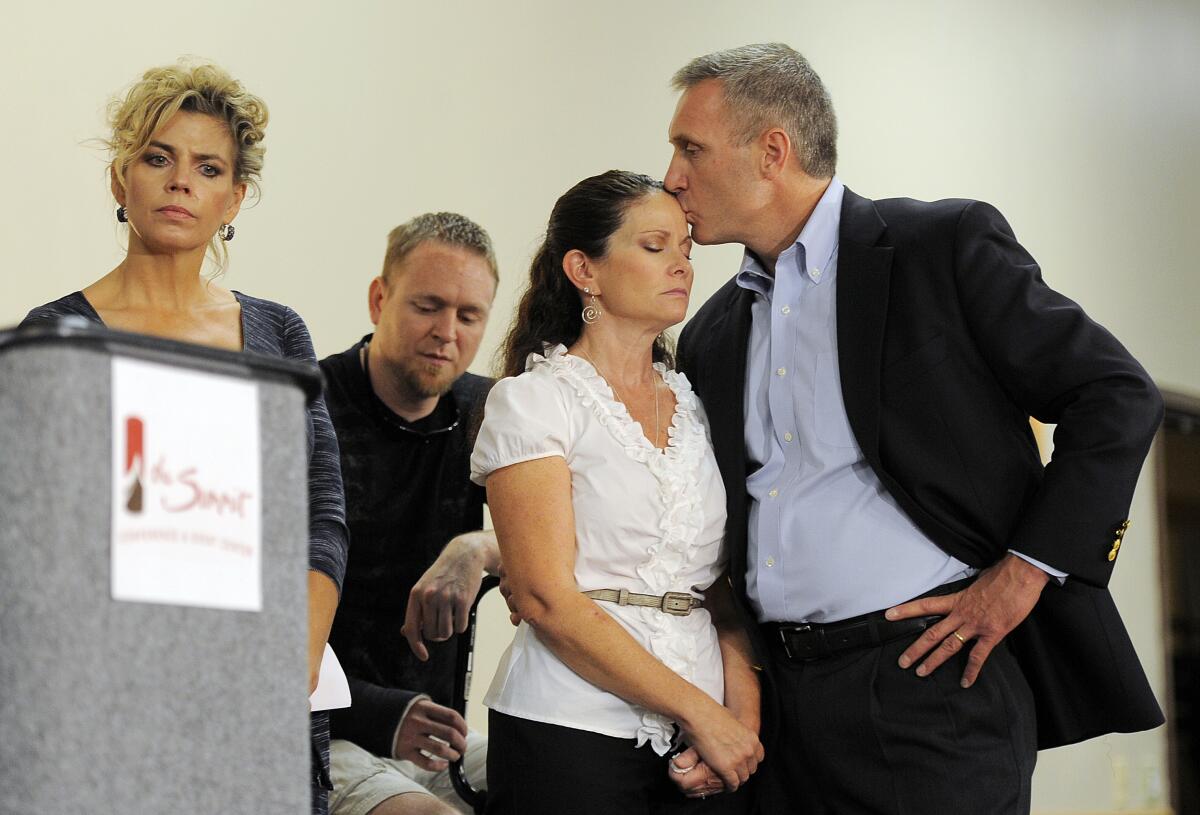

After their son’s death, Teves and his wife, Caren, launched an organization called No Notoriety with the goal of denying mass shooters the fame they often seek. They try to persuade media organizations not to publish the names of the shooters or photos that would make them look impressive or intimidating.

These recommendations, which have been adopted in some form by the FBI and many other law enforcement agencies, are based on a growing body of research that says shooters are influenced and inspired by media coverage of other shooters — and that media attention is one of their main goals.

It’s too late for my son. The goal now is to save someone else’s.

— Tom Teves

“These perpetrators are specifically seeking a legacy,” said Adam Lankford, a professor of criminology at the University of Alabama.

One study of the deadliest 31 mass shootings since 1966 found that 87% of mass shooters expressed an explicit or circumstantial desire for fame and attention. Another study found that many mass shooters used previous mass shooters as inspiration, role models and idols, fueled by reporting on their backgrounds.

In 2015, researchers documented a contagion effect for mass shootings, offering mathematical proof that mass shootings incited subsequent mass shootings. They calculated that there’s a heightened chance of mass shootings for a 13-day period after one occurs, and that one school shooting incites an average of .22 new incidents. Intensive media coverage played a role, the study says.

A review of mass-shooting coverage by the media also revealed disproportionate attention paid to the shooter — 16 times more images of shooters are published than are those of their victims — according to a recent study.

Those images, and the reams of content we produce about these incidents, fuel a long-standing online subculture in places like Tumblr, Facebook, DeviantArt and YouTube. In these forums, devotees of mass murderers (the Sandy Hook shooter was one) discuss strategies, share articles and debate murderers as if they were favorite athletes.

These spaces incubate future shooters. And repeated media exposure to violent acts breaks down the taboo of killing in the mind of a potential mass shooter, said Peter Langman, an expert on the psychology of mass killers.

“We’re seeing a rise because the phenomenon is feeding on itself,” Langman said. “Every time the taboo is broken, it makes it easier for the next person to cross that threshold.”

This research presents a disturbing challenge to journalism’s values. The science tells us to report on shooters without drama and avoid lionizing or humanizing their actions, which can turn them into antiheroes. But our principles say that truth, drama, action and character are the basic building blocks of stories.

We rank the shootings in order of magnitude to give readers a sense of their historical significance and scale. But research says those rankings, by number of dead and wounded, are treated like video game scoreboards by potential shooters, who then kill more so they can rank more highly.

Every time a mass shooting occurs, reporters come together in an incredible display of teamwork, dedication and sacrifice to write a ticktock, an objective, vivid and comprehensive account of everything we know about the shooting. It serves the public to have a verified record of what happened and helps hold officials accountable to the truth.

Then we send our best storytellers to uncover the motivations of the shooter and share the pain of the victims’ families. Because in the days after a horrific event, a nation in mourning wonders why — and it’s journalism’s job to answer.

But research says these stories, which are often gripping and contain descriptions of graphic violence, fuel the fantasies of the next mass shooter. The more compelling and widely read these stories are, the greater the imagined payoff for a mass shooting.

How do you tell a story about a mass shooting when research tells you that storytelling itself is part of the problem?

::

When I’ve reported on mass shootings or tragedies in general, I‘ve told myself that there’s power in bearing witness, and that it’s my job to give people information. I’m trying to express the magnitude of what the shooter took away, not just from the victim’s family, but also from society. I imagine that I have the power to transform the pain of a family’s loss to action and meaningful change.

I tell myself this because I’ve seen it happen at least a few times, in other situations.

But I’ve also created these rationalizations because you have to tell yourself something, when you find yourself in a crowd of cameras and reporters outside the home of a victim, waiting to be the 10th or 12th person to interrupt the fresh, raw grief of the victim’s mother, only to repeat the same lifeless condolences and useless apologies as everyone else who knocked on that door before you.

I still tell myself these things, but I don’t know if I believe them anymore. I’ve lost count of the mass shootings that have occurred since the first one I covered in 2013. I can’t wrap my head around all of the violence and the pain, and I’m exhausted by the circular and rapidly polarized discourse that roars into being moments after the news breaks. I think we all are.

And now I wonder if the simple act of bearing witness still has power in an age when information and images reach audiences in hyper-politicized, often inaccurate form over social media, without context and sourcing.

Have we turned all of the victims’ pain into anything useful? Does it matter if we change readers’ hearts and minds if their congressman never responds when those readers call and ask for change? What good is telling a moving story if no one is ever moved to action?

We journalists love to take credit for the good that journalism can do. But we also have to take responsibility for the harm that we can cause.

This industry has embraced change before, when presented with compelling research that showed that media attention paid to suicides caused more death.

In 2001, the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institute of Mental Health and many other groups banded together for a joint report with recommendations on how to report on suicide.

The surgeon general at the time, David Satcher, announced the recommendations at a nationally televised news conference. Dan Romer, director of research at the Annenberg Public Policy Center, worked on the report and presented its findings at journalism conferences across the country.

He met with editors and deans of journalism schools and mailed thousands of brochures with recommendations to newsrooms. Groups worked together to monitor stories about suicide and send messages to journalists who had failed to follow the guidelines.

It was a huge, coordinated national effort, with slow but significant impacts. Though there are still plenty of mistakes, news organizations now typically avoid reporting on suicide unless in special cases.

But no such concerted effort yet exists for mass shootings, Romer said. It’s harder to study mass shootings because the sample sizes are smaller than for issues like suicide, and federal funding for gun violence research is held hostage by political gridlock.

And shootings are hugely significant, relatively rare news events that can’t be kept off the front page like suicides. Even if journalists decide not to use the photo or the names of shooters, a vast ecosystem of other sites will. It may be impossible to deny mass shooters notoriety completely.

But Lankford says many shooters express — whether in manifestos, interviews or online posts — a craving for the prestige of having their name and face in a major publication. And we can do something about that.

“I’ve never heard anyone offer a cogent argument as to why seeing the face of a mass shooter is somehow helpful information for understanding how to prevent the next one,” Lankford said.

When Teves began his crusade, he thought it was going to take two or three months at most. There have been so many shootings since then, so many media appearances, so many re-treadings of his family’s loss.

It pained me to ask Tom to tell his story once again. I worry that I’ve wasted his grief once again. This is not the first article written about the media’s role in mass shooter contagion.

But it’s not on politicians or policymakers to turn his pain into meaningful action. He’s not waiting for tighter background checks, restrictions on assault weapons, a better mental health safety net and warning system, though all of those things would help.

He’s waiting for us to change the way we report on mass shootings.

“That doesn’t take an act of Congress,” Teves said. “It takes an act of conscience.”

More from Frank Shyong

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.