Earthquake shook L.A. skyscrapers so hard some got vertigo

- Share via

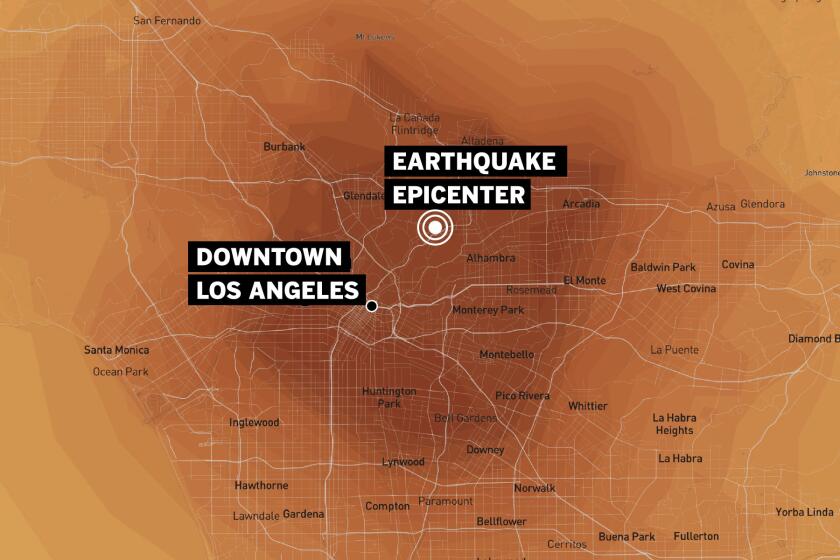

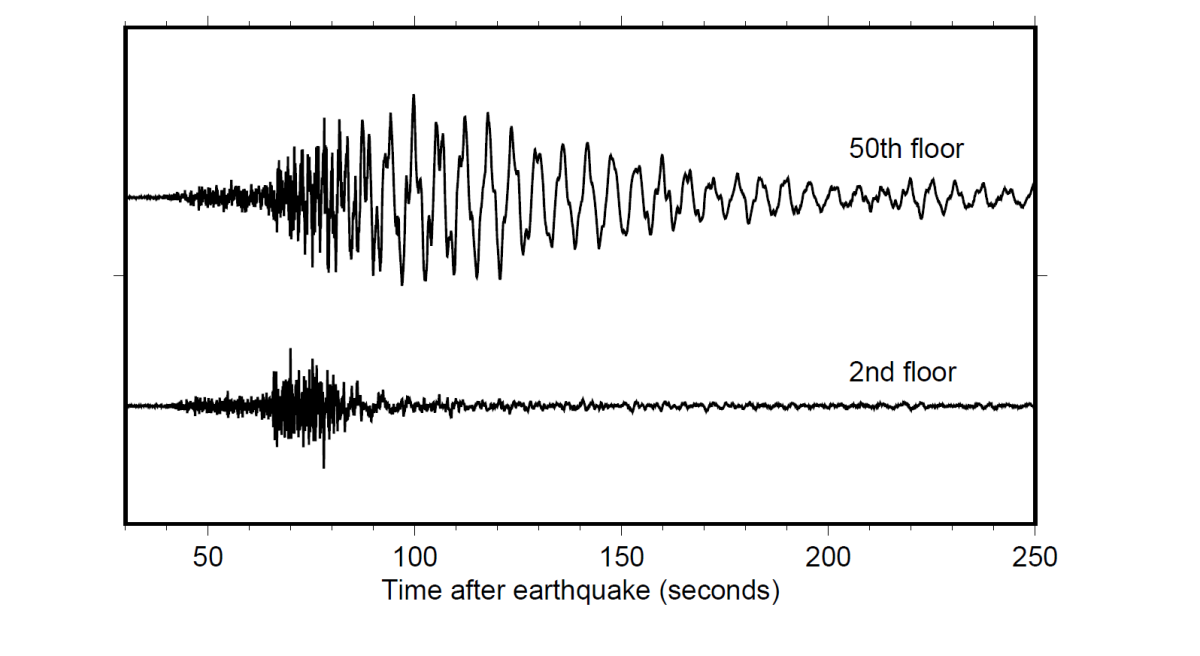

If you were sitting in the lobby of one particular downtown Los Angeles skyscraper when energy from the magnitude 7.1 Ridgecrest earthquake arrived, you might have felt a few seconds of light shaking.

But up on the 50th floor, the experience was terrifying. The building — equipped on each floor with seismic sensors — swayed back and forth for perhaps two to three minutes and as much as one foot in each direction, said Caltech research professor of civil engineering Monica Kohler.

On the 48th floor of another building in downtown Los Angeles, Beth M. Foley said she felt vertigo, and her husband motion sickness, after what seemed like minutes of swaying. Eventually, the building creaked and came to a stop. The couple said they plan to pack anti-nausea medications in their earthquake kit. “These things swayed like loblolly pines in a storm,” Foley said.

“That’s going to do a number on your brain,” Kohler said. “Seasickness is something you get when you’re in these high-rises.”

The observations speak to the way the July 5 Ridgecrest earthquake — the strongest with a Southern California epicenter in the age of the internet and smartphones — is providing scientists a trove of remarkable data.

An effort by Caltech that began eight years ago, called the Community Seismic Network, has resulted in the installation of 1,000 sensors across the region, on buildings owned by the Los Angeles Unified School District, USC and Caltech as well as other privately owned buildings. Having the devices — which were funded by the National Science Foundation, the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation and Computers & Structures Inc., among others — placed on every floor of a building provided especially illuminating information.

For one, the duration of the shaking and the distance that the top of the L.A. skyscraper swayed back and forth, while well within the normal range, were still surprisingly long and far, Kohler said.

“We saw the upper third of the high-rise sway back and forth a lot,” Kohler said.

Sensors at two nine-story buildings at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge recorded unexpected results: strong shaking that came in not one, but two pulses. One of the bursts may have resulted from energy that was reflected off something underground — perhaps the bottom of the sediments that have eroded off the nearby San Gabriel Mountains, a layer below those sediments or one on the edge of the basin — and back to the surface, Kohler said.

“The double pulse did surprise us, the amplitude of both of those pulses was equally strong,” Kohler said. The observation shows how hard it can be to know if the worst of the shaking is really over.

U.S. Geological Survey seismologist Rob Graves said he felt something similar in Pasadena, about 100 miles from the epicenter — one wave of shaking comes through, then dies down, only to be followed by another.

Instruments across California recorded varying durations of the strongest shaking emanating from Ridgecrest.

A device at the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, about a mile away from the ruptured fault, showed it lasted for a relatively short period, Graves said — perhaps 15 to 20 seconds.

But that was on bedrock, said USGS seismologist Susan Hough. Shaking energy that feeds into softer sediments can increase the intensity felt at the surface and last dramatically longer.

A 6.4 magnitude earthquake struck Southern California on the morning of July 4 near Ridgecrest, about 100 miles from Los Angeles.

The city of Ridgecrest, on softer sediments that have eroded off of mountains, probably felt about 35 seconds to 45 seconds of strong shaking, Hough said; there was also a longer period of sloshing that continued for some time as shaking waves reverberated across the Indian Wells Valley, along with shaking from aftershocks.

U.S. Geological Survey geophysicist Ken Hudnut said he felt a rapid back and forth in Ridgecrest.

“If I had been on my feet, I probably would’ve been knocked down,” Hudnut said. Eventually, the sharp and violent motion gave way to a more rolling movement. And even after the strongest shaking subsided, he said, the ground continued to vibrate and feel unsettled.

Many California cities lie atop soft sediments that can act like quicksand when shaken — a process called liquefaction.

In fact, much of the flat land known as the Los Angeles Basin sits atop an area of soft sediment so enormous that it has filled up a valley underlain by old, dense crystalline rock.

Scientist knew almost immediately that the Ridgecrest quakes were not on the San Andreas fault. But understanding how those temblors might impact the 730-mile monster capable of producing “The Big One” has been a vital.

The basin is deepest at the intersection of the 710 and 105 freeways, according to USC earth sciences professor James Dolan, where you’d have to dig 30,000 feet through soft sediment to reach the crystalline rock — a valley as deep into the Earth as Mt. Everest is tall.

The basin reaches to the northwest toward Beverly Hills before the Santa Monica Mountains ends it, and to the southeast into northern Orange County.

How thick the sediment is in a particular spot, and the shape of the boundary between the sediment and the harder rock below, is key when it coming to shaking intensity.

For instance, in the L.A. region, the shaking energy you feel first may be waves that have hit the bottom of the underground valley and reflected back up to the surface. Then a second wave of shaking energy may come from the horizontal direction, where shaking waves travel slower, Graves said.

The direction of a quake also matters. If you happen to be right in the path where the fault rupture was going through — such as along the same northwest-southeast orientation as the July 5 quake — it would feel “like a freight train was coming at you,” Hough said.

Ridgecrest got a glancing blow, as it was southwest of the ruptured fault.

ShakeAlertLA, the early warning app, will now issue alerts for weaker shaking after the Ridgecrest quakes in July didn’t register in L.A.

In the magnitude 6.7 Northridge earthquake of 1994, the worst shaking hit north of the San Fernando Valley, targeting Santa Clarita, Valencia and Newhall. The fault rupture began 12 miles underneath Northridge — along a mostly horizontal, sloping fault — and then continued northward and got shallower as it ended about four miles underneath the Interstate 5/Highway 14 interchange, which collapsed, causing the death of a Los Angeles Police Department officer who drove off the end of a broken overpass.

There have been other surprising observations scientists are still figuring out.

Given that Los Angeles is about 125 miles from the Ridgecrest epicenter, and the city’s orientation to the ruptured fault, researchers expected that the strongest shaking in high-rise buildings would’ve been evenly distributed in north-south and west-east directions. Surprisingly, some of the strongest shaking detected in high-rise downtown buildings was in the east-west direction, Kohler said.

One possible explanation is that shaking waves didn’t come in the same direction as a crow flies; as the shaking hit mountain ranges, the energy waves may have taken a circuitous path around them. Another explanation might be that the east-west shaking waves that made it to L.A. were more resonant with the natural frequency of the downtown L.A. high-rises, and thus were more obvious, Kohler said.

For the record, 5 p.m., Aug. 19, 2019: An earlier version of this story had incorrect details regarding the death of a law enforcement officer during the 1994 Northridge earthquake. The officer was with the Los Angeles Police Department, not the California Highway Patrol.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.