Ghost Ship verdict: Jury acquits one defendant, deadlocks on second in warehouse fire that killed 36

- Share via

The two men accused of turning an Oakland warehouse into an arts collective that became the site of one of the deadliest blazes in California history avoided criminal punishment Thursday, marking a stinging defeat for prosecutors and the victims’ families after a years-long battle over who was truly responsible for the 2016 Ghost Ship fire.

A Bay Area jury acquitted Max Harris, the warehouse’s 29-year-old self-described “creative director,” of 36 counts of involuntary manslaughter in connection with the roaring blaze. The same jury could not reach a verdict on charges against Derick Almena, 49, the warehouse’s property manager who had become the public face of the tragedy.

Ten jurors voted to convict Almena, but two others called for an acquittal. If convicted, both men would have faced 36 years in state prison. It was not immediately clear if prosecutors would attempt to retry Almena.

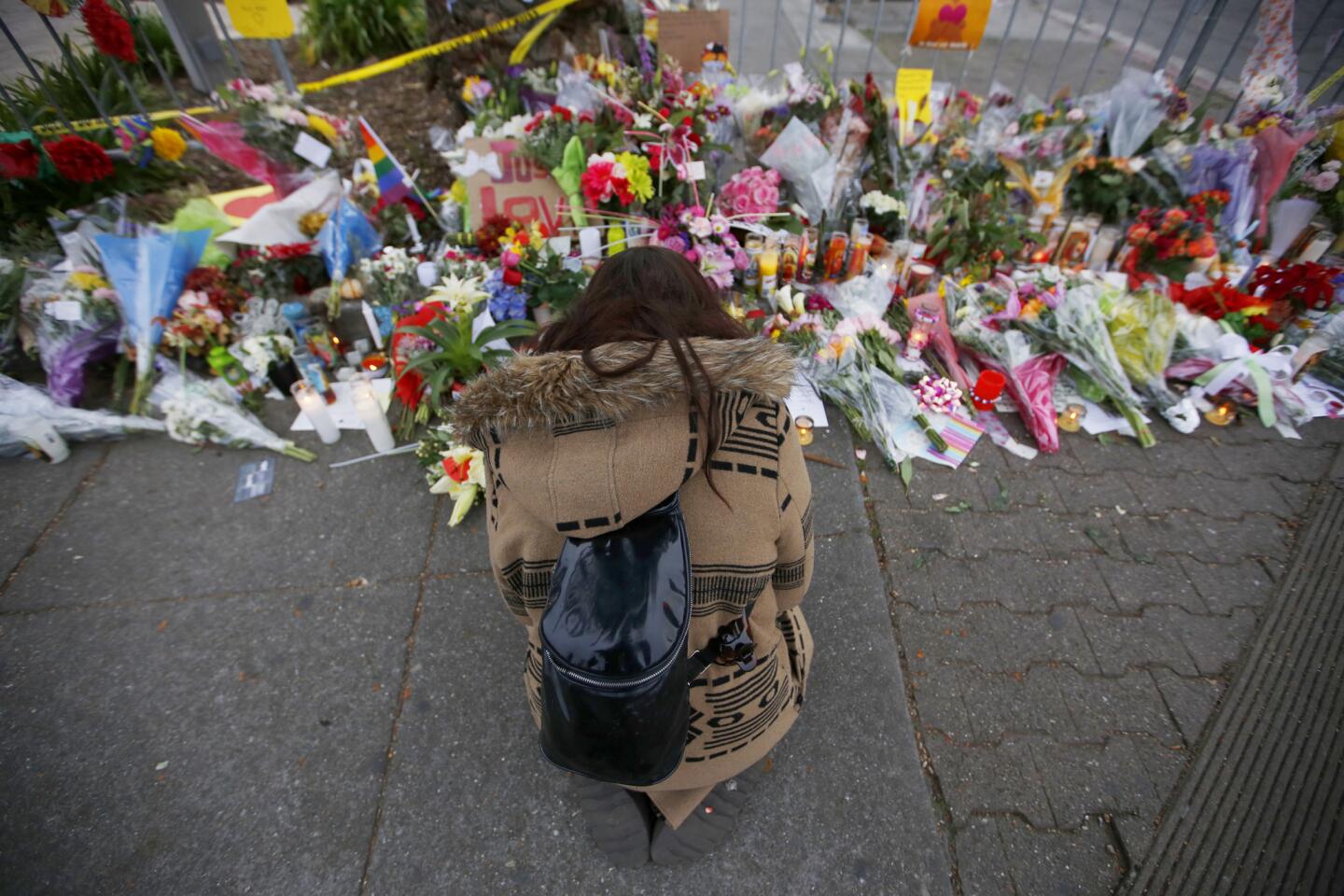

For the victims’ loved ones, many of whom had either sat in court and listened to heart-rending testimony about their relatives’ final moments during the four-month trial or flown back and forth from other parts of the country to attend key hearings, Thursday’s result was the latest round of pain and frustration.

“You have 36 people who died and there’s no one taking responsibility for this,” said Grace Kim, whose cousin Ara Jo died in the fire.

The announcement marked the end of a saga that involved two trials, an aborted plea deal and a near-mistrial.

Almena and Harris reached an agreement with prosecutors last year during the first criminal trial, but the deal was tossed by a judge after several of the victims’ relatives protested that the sentence was too light.

The second trial spanned from April to August of this year, and nearly ended in a mistrial after 10 days of jury deliberations.

On Aug. 19, Alameda County Superior Court Judge Trina Thompson called several jurors in for one-on-one questioning before seating three alternates, admonishing the panel to refrain from discussing the case with anyone and ordering deliberations to restart.

J. Tony Serra, Almena’s lead defense attorney, said Thursday he was not satisfied with the mistrial and vowed to win an acquittal for Almena should prosecutors seek to try him again. He also expressed sympathy for the victims’ families.

“They should be less interested in a retrial,” he said. “Maybe they will be, maybe they won’t. Some of them forgive and forget, others will want revenge.”

Prosecutors did not take questions during a brief news conference Thursday afternoon. In a statement, Alameda County Dist. Atty. Nancy E. O’Malley said she was “disappointed” with the verdict but respected “the thoroughness and thoughtfulness of each juror in this matter.”

The final jury had received several days off in late August, and had only been deliberating for about six days before Thursday’s verdict. Almena is due back in court on Oct. 4, prosecutors said.

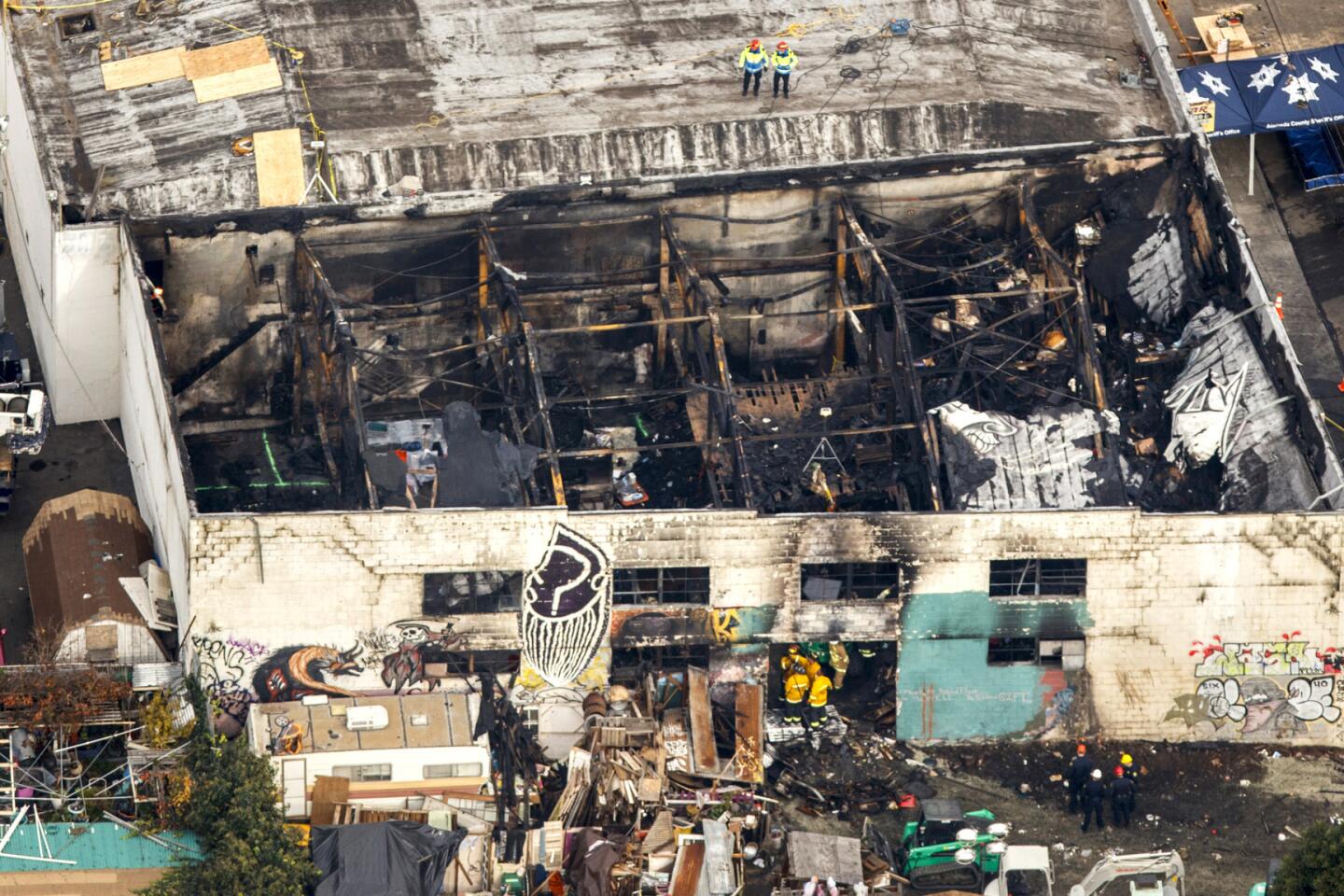

Prosecutors accused Almena and Harris of converting the Ghost Ship building into a death trap through a series of illegal construction projects and shoddy electrical work. The structure was filled with pianos, tapestries, furniture and other items that acted as kindling when the blaze broke out on Dec. 2, 2016. There were nearly 100 people inside during the concert, and prosecutors said Harris had closed off one of only two exit routes, forcing victims fleeing the fire to navigate a rickety staircase made of wooden pallets.

All 36 victims died of smoke inhalation. Almena and Harris were first charged in June 2017, roughly six months after the blaze.

An investigation spearheaded by the U.S. Department of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives could not determine the cause of the fire. Most of the evidence they would have needed to prove its origins was swallowed by the blaze, investigators said.

Serra repeatedly seized on that fact at trial, suggesting the fire was the result of arson after a group of men lobbed Molotov cocktails at the structure. Much of Almena’s defense involved deflecting blame onto other parties, namely the building’s landlords.

Almena testified that he begged Chor Ng and her children, Eva and Kai, to make improvements to the building that would have helped with fire safety and electrical problems, but said he was repeatedly ignored.

“They did absolutely nothing,” he said on the stand in early July. “I did my best.”

Ng was never charged, but she has been named in multiple civil lawsuits brought by the victims’ families.

Prosecutors contended the blame rested solely with Almena and Harris. Alameda County Deputy Dist. Atty. Autrey James focused heavily on Almena during his closing arguments, telling jurors that 35 of the victims died on the upper level of the warehouse because they received no warning about the blaze until the fire was closing in around them.

James said the failure to install smoke alarms or sprinklers lay with Almena, who, he said, ignored repeated requests to obtain proper permits because he wanted to avoid inspections.

The building was not zoned for residential use, yet Almena charged people between $300 and $1,400 a month to rent space, and in some cases, to live out of the Ghost Ship. Almena has said he used that money to cover his $4,500-per-month lease agreement with Ng.

Almena and Harris were set to agree to a plea deal last year that would have seen them serve nine and six years in prison, respectively, but a judge rejected the deal after an impassioned outcry from several of the victims’ families.

When he testified in July, Almena tried to convey the sense of grief he felt over the carnage caused by the fire.

“You can’t put into words how I feel,” Almena said. “You can’t judge my heart.”

Harris’ defense counsel spent most of the trial trying to distance his client from Almena, and minimize his role in the oversight of the warehouse’s day-to-day operations. His lead attorney, Curtis Briggs, said Thursday that while he sympathized with those who lost people in the fire, the jury reached the correct outcome.

“I apologize if anything that we did inflamed [the victims’ families],” he said. “I was always under the belief that Max Harris was innocent and I did what I had to do to get him home.”

The tragedy also highlighted stresses in the Bay Area’s out-of-control rental market, where tenants often complain they are at the mercy of landlords charging astronomical prices while refusing to make basic improvements to their properties. And it pointed up the failings of Oakland city officials to monitor properties like the Ghost Ship.

Public records released after the fire showed the warehouse had been subject to at least 10 code enforcement complaints and that city officials had visited the building numerous times, but failed to go inside or move to shut it down. Almena also testified that Oakland police and fire officials knew people were living inside the warehouse.

Tyler Smith, another attorney who represented Harris, told reporters Thursday that the city’s housing crisis created a situation that was ripe for disaster.

“None of this ever would have happened in the first place if the income inequality, the injustice … and the housing crisis, wasn’t permitted to get as bad as it has gotten in the Bay Area, and in Oakland, in the last few years,” he said. “These artists were living in this warehouse because … they were going to be living on the street otherwise.”

The verdict marked the end of a long journey for many of the victims’ relatives.

David Gregory, whose daughter Michela was among those killed in the fire, has attended nearly every hearing in the case since Almena and Harris were arrested in 2017. Every day, he’d wearily enter the courtroom after working a graveyard shift as a diesel mechanic. He’d go home from court at 5 p.m. each day, start work at 11, then repeat the cycle.

Kim said she didn’t know if she’d be able to face another trial.

“I was only there for a week, and I was exhausted. … I know that some of the other families have had illnesses, psychosomatic symptoms from the stress of going through this and listening to the testimony and hearing the gory details of how our family members have died,” she said. “I don’t know if I have it in me to keep flying out to make statements. I feel like I need to do it for my cousin.”

Times staff writers Colleen Shalby, Hailey Branson-Potts and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.