California ignores the science as it OKs more homes in wildfire zones, researchers say

Researchers say continued home building in high-risk wildfire areas threatens lives and makes big blazes more likely.

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — California’s top firefighting authorities want to use chainsaws and flames to thin out forests and mow down brush on at least half a million acres a year from Redding to San Diego.

The plan — which aims to roughly double the current pace of so-called vegetation management within five years — comes at the behest of Gov. Gavin Newsom and is the state’s primary response to the massive blazes that have ravaged communities across the state.

However, an emerging body of scientific research on patterns of homes destroyed by fire suggests the state’s approach may be ignoring one of the most crucial elements for keeping people safe and limiting wildfire ignition sources.

Scientists have increasingly found that loss of property and life from fire is overwhelmingly the result of precariously placed housing in and bordering wildland areas — residential developments that are, themselves, a major driver sparking conflagrations.

More than 90% of fires in California are started by humans, often along roads and buildings lined with flammable invasive grasses.

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, known as Cal Fire, has largely sidestepped any discussion of whether fire-prone landscapes should be off limits to new home construction.

Cal Fire has acknowledged that housing construction continues in and around the state’s wildlands, where about 11 million people now live in 4.5 million homes.

Beyond cutting and burning down natural landscapes, the state’s response to the threat of wildfire has been to require that new home construction use the latest in fire-resistant materials, encourage retrofits of older structures and improve roads used as evacuation routes.

“The physical location of being out in the WUI [wildland-urban interface] doesn’t mean that the communities will be entirely burned down like we saw in Paradise if they’re built to the latest standards,” said Steve Hawks, Cal Fire deputy chief overseeing the Wildland Fire Prevention Engineering Program.

Hawks also downplayed the idea that building new homes in and around fire-prone areas would create more ignition sources, leading to more backcountry blazes.

“The state’s growing,” he said. “You’re going to find that people travel, they vacation out in the WUI areas. There’s a certain amount of fires that are going to happen no matter what anyone tries to do to prevent them.”

In response to questions, the governor’s office pointed to an often-quoted article from April by the Associated Press in which Newsom said that restricting building in high-fire areas would run counter to the state’s “pioneering spirit.”

That position has fueled a growing frustration among wildfire researchers who have been calling for an open debate about whether and to what extent new housing should be limited in fire-prone areas, similar to restrictions in flood plains.

Char Miller, a professor of environmental analysis at Pomona College and widely recognized wildfire policy expert, said the state’s focus on cutting down trees and scrubland is an “obfuscation” to take pressure off elected leaders.

“There’s no conversation other than the vegetation management conversation about what to do about wildfires,” Miller said. “I think that’s pretty deliberate.

“We can’t proclaim ignorance or innocence,” he added. “We have all of the information we need. What we don’t have is political leadership at any level.”

State officials have countered that the focus needs to be on protecting existing communities in high-fire areas, such as by paving new evacuation routes and helping residents pay for upgrades to their homes.

“The notion that this is all about how we will plan our future developments ignores the 800-pound gorilla of the built environment as it exists on the landscape today,” said Keith Gilless, professor of forest economics at UC Berkeley and chairman of the state’s Board of Forestry and Fire Protection.

The approval process

Without California-wide standards, local elected officials have broad discretion when it comes to approving the location of new developments. When faced with public resistance, county lawmakers overseeing wildland areas often call on regional firefighting authorities to testify to the safety of specific projects.

The San Diego County Board of Supervisors, for example, has approved thousands of units of new housing in high-fire-severity zones over the last 18 months with the support of Cal Fire. Such projects must meet a wide array of state and local requirements, such as building materials, road lengths and ensuring firefighters have access to water.

In June, the board narrowly approved the 1,119-home Adara at Otay Ranch, planned along a two-lane road in an area routinely scorched by wildfire, including the devastating 2007 Harris Fire.

Scores of people gave testimony in opposition, including fire-dynamics expert and building consultant Chris Lautenberger.

Lautenberger, co-founder of Reax Engineering, told the board that the project not only puts residents of the new development at risk, it could exacerbate fire danger for nearby communities.

“Building 1,100 homes … greatly increases the chances of fires igniting there simply due to the presence of people, vehicles, roads and homes in what is a currently largely undeveloped area,” he said, adding: “Under strong Santa Ana wind conditions, it would spread rapidly toward Chula Vista where several hundred structures would be destroyed within a few hours.”

Elaborate sprinkler systems could be a waste of money in protecting your home from wildfire. A better strategy, experts say, is to team up with neighbors to fireproof your entire community.

Three of the board’s five members voted to approve the project, pointing to the testimony of San Diego Cal Fire Unit Chief Tony Mecham, who after numerous questions by Supervisor Greg Cox agreed that the project represented a “fire-safe community.”

Specifically, Mecham said he felt comfortable supporting the housing development because it would use the latest in fire-resistant building materials, clear away large amounts of vegetation and include the construction of a new fire station.

About a month later, Cal Fire Fighters Local 2881, which represents about 650 Cal Fire employees in San Diego County, came out publicly in support of another controversial project, Newland Sierra, which is also located in an area designated by Cal Fire as a fire-hazard zone.

Approval of such projects up and down the state — often years in the making with hundreds of millions of dollars in profit at stake for developers — has shocked and angered some environmental groups.

“It’s this disaster industrial complex,” said Dan Silver, chief executive of the Endangered Habitats League. “I thought the fire people would have been the best friends of not doing more remote building.”

Research on wildfire destruction

Elected officials in Southern California have long maintained that identifying areas too risky to build is not realistic because even urban areas are at high risk for fire damage.

However, that’s not what the science has found.

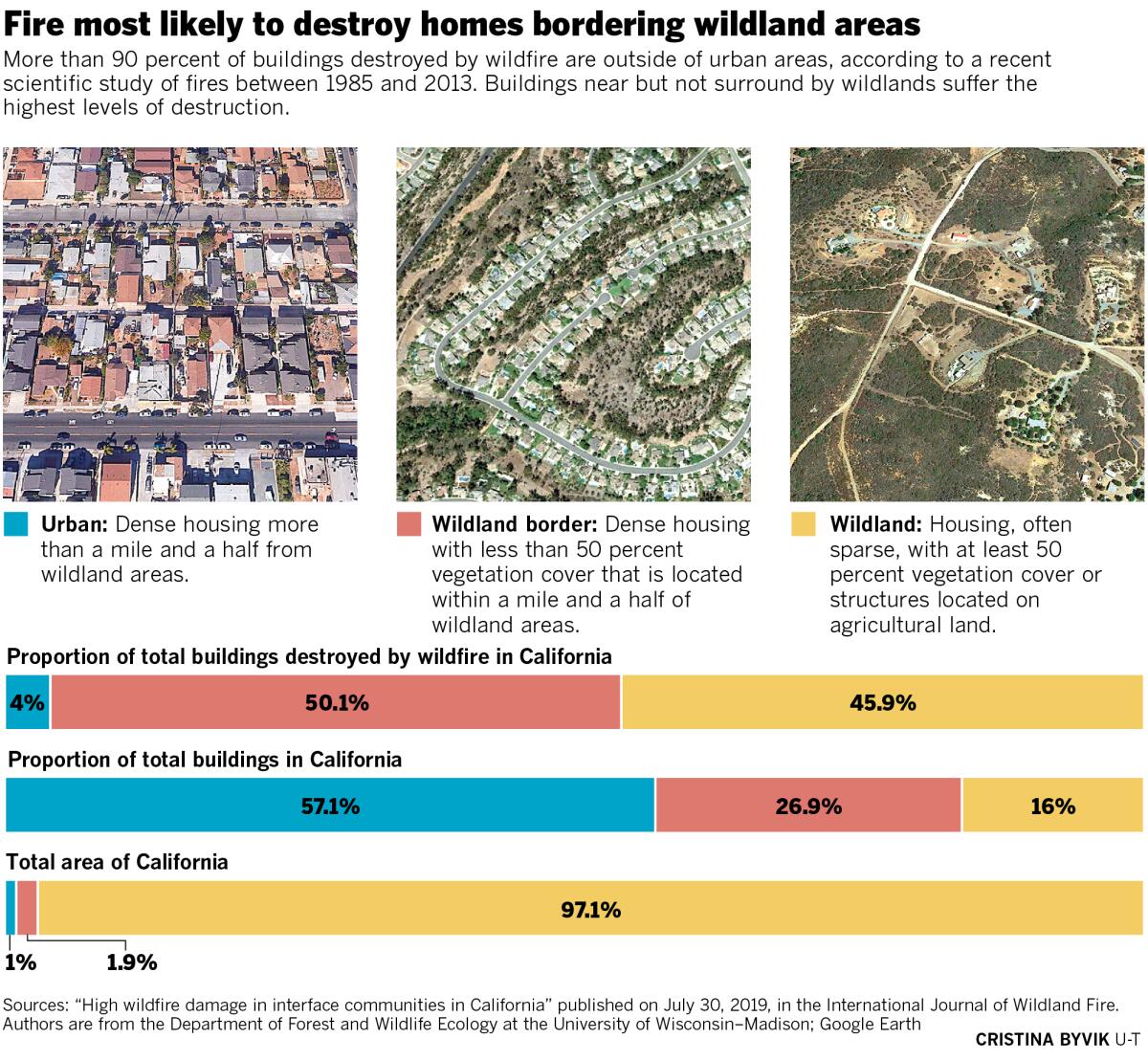

A recent study out of the University of Wisconsin—Madison’s Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology and the U.S. Forest Service found that more than 90% of homes destroyed by fire in California are outside of urban areas.

Perhaps surprisingly, housing developments bordering wildland areas saw the most destruction, even compared with those more remotely located, according to the paper published July 30 in the International Journal of Wildland Fire.

The findings underscore a pattern of devastation that researchers and firefighting authorities have increasingly come to recognize. Wildland fires that threaten people and homes in California are not the result of large forest fires. They are wind-driven blazes that pepper nearby communities with blazing embers.

Those firebrands get inside vents, lodge in unprotected eaves and ignite homes from the inside out. Then that fire travels house to house, often carried by nonnative vegetation planted by residents.

In fact, post-fire analysis has suggested that larger trees often play a limited role in spreading fire among wildland communities.

“Certainly, there were areas where just everything got torched,” said Anu Kramer, coauthor of the report and a researcher at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. “But it was not uncommon to see areas where the trees were still intact and the houses were gone.”

This was largely the case in the state’s most deadly blaze, the Camp Fire, where a wind-driven fire swept through an area that had been heavily logged, dropping embers on the town of Paradise. When the smoke cleared, many trees were left standing among the rubble.

“It’s really common to see post-fire neighborhoods and there’s a lot of the vegetation left,” said Max Moritz, a wildfire specialist with the University of California Cooperative Extension. “You realize, it was embers that started some of the homes on fire, and then the homes themselves generated a bunch of heat and fire that caught the neighboring homes on fire.”

So why is California preparing to spend millions to cut back trees and shrubs, many of which provide habitat for native species? Cal Fire has acknowledged some of the limitations of vegetation management, but the agency maintains that cleared areas provide key staging grounds from which firefighters can battle oncoming flames.

Experts have debated the merits of creating so-called fire breaks, but they generally agree that such projects require annual maintenance to ensure that ripping out native vegetation doesn’t lead to the proliferation of highly flammable invasive plants.

What is less settled is how to best protect homes from being ignited when firebrands blanket a community.

Much of the state’s focus has centered on maintaining defensible space, aggressive landscaping within a 100-foot radius around a home. Of most concern is dead vegetation and tree limbs that overhang roofs.

A recent Union-Tribune investigation revealed that Cal Fire faces significant challenges enforcing such rules, but the state has pledged to increase its efforts.

Still, a scientific study published Sept. 2 in the journal Fire found that defensible space is one of the least important factors in determining whether a home burns in a wildfire, especially vegetation removal beyond the first 5 to 10 feet around a home.

The report analyzed an extensive Cal Fire database of more than 40,000 wildfire-exposed structures from 2013 to 2018 affected by some of the state’s most destructive blazes, such as the Camp and Woolsey fires.

The research found that by far the most effective measures homeowners can take to protect homes is to install ember-resistant vents and double-pane windows and to box off eaves.

“What people are not aware of is that if you take your nice evergreen shrub and clear it away and put grass in there, you’re actually making it more flammable,” said coauthor Alexandra Syphard, chief scientist at Sage Insurance Holdings and one of the foremost experts on wildfire and housing in the state.

“People are getting the wrong message,” she said. “They’re thinking, ‘OK, I just need to clear away all this brush.’ That’s not the safest way to go about it.”

Emerson Smith writes for the San Diego Union-Tribune.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.