Only half of California students meet English standards and fewer meet math standards, test scores show

- Share via

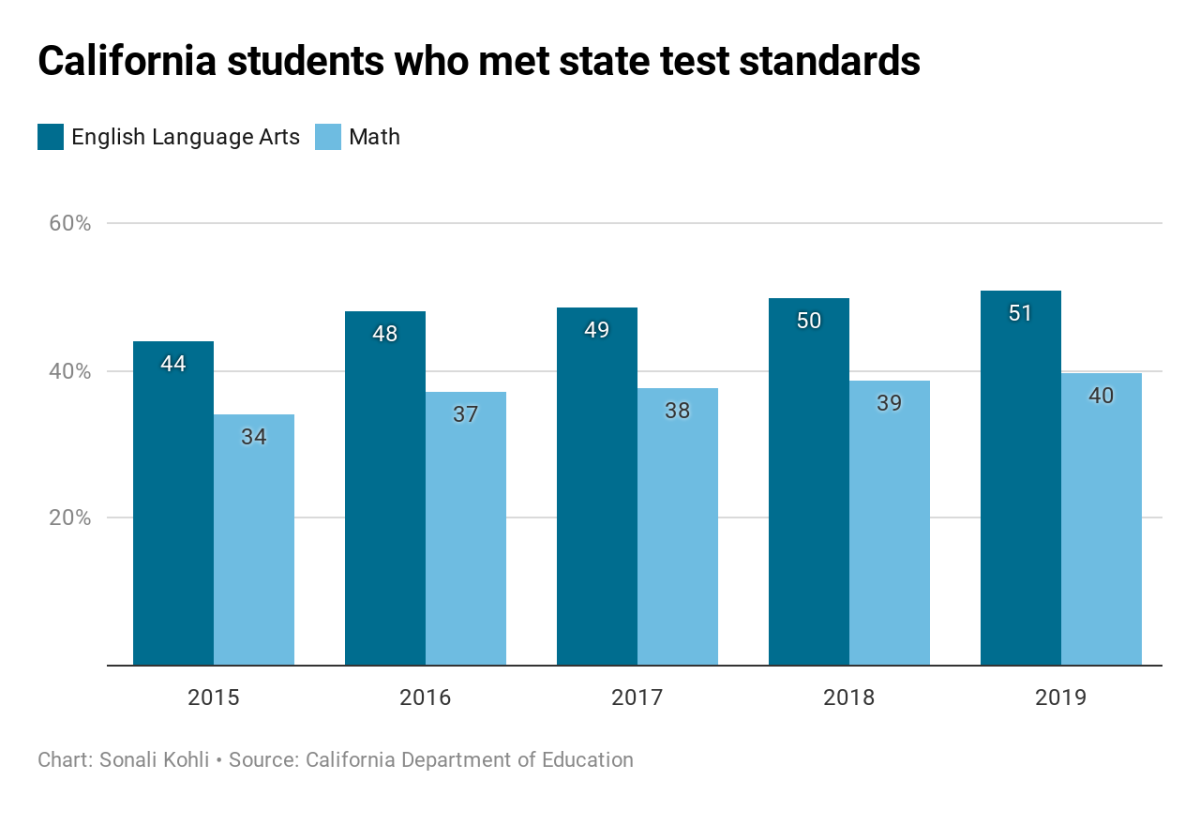

Just over half of public school students who took the state’s standardized English language arts test performed at grade level, while only 4 in 10 are proficient in math, scores that represent a slow upward trend over the past four years, according to data released Wednesday by the state Department of Education.

Proficiency rates rose about 1 percentage point each in both English and math between 2018 and 2019, with 50.9% of students meeting English standards and 39.7% of students meeting math standards on the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress, designed to test Common Core concepts. However, scores among African American students are markedly lower, prompting calls from educators to address the achievement gap.

Although the overall incremental progress is a good sign, education experts said it’s troubling that the majority of public school students test below grade level in math, and nearly half in English. Students in grades three through eight and 11th-grade high school juniors take the test. The low scores reflect a lack of investment in early childhood education and in the public school system, the experts said.

“We don’t have high-quality preschool available; the same supports that you see in the affluent, suburban and private schools, you don’t see in the public schools serving poor kids,” said UCLA education professor Pedro Noguera.

“No one ever says, ‘Wow, we should do for the kids in Compton what we do for the kids in Brentwood,’” where a plethora of expensive private schools with small class sizes serve the wealthy, Noguera said.

Students at California charter schools, which are publicly funded but operate independently, performed about the same in English — 50.51% were proficient — but lagged in math, where 36.65% of charter students met or exceeded standards.

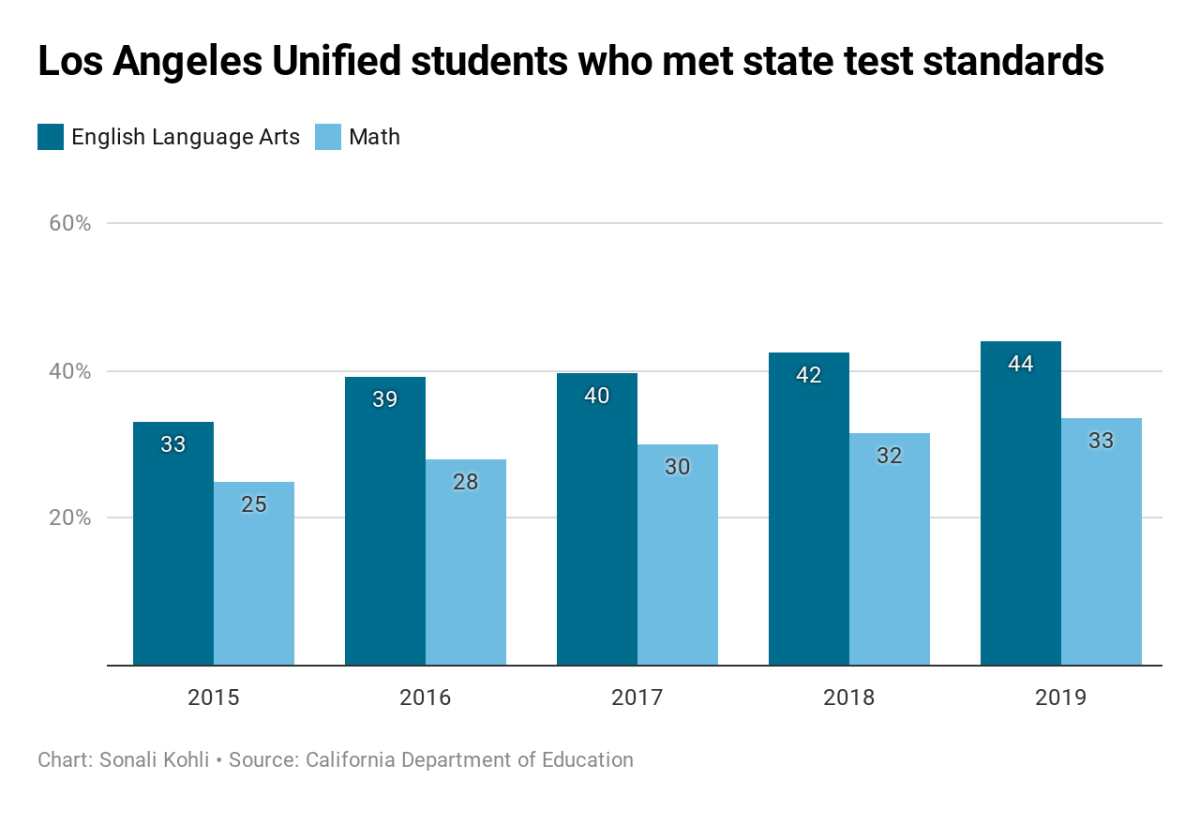

In Los Angeles — where about 80% of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, an indicator of low family income — scores improved at a higher rate, almost 2 percentage points in each category: 43.9% of students met English standards in 2019, and 33.47% met math standards.

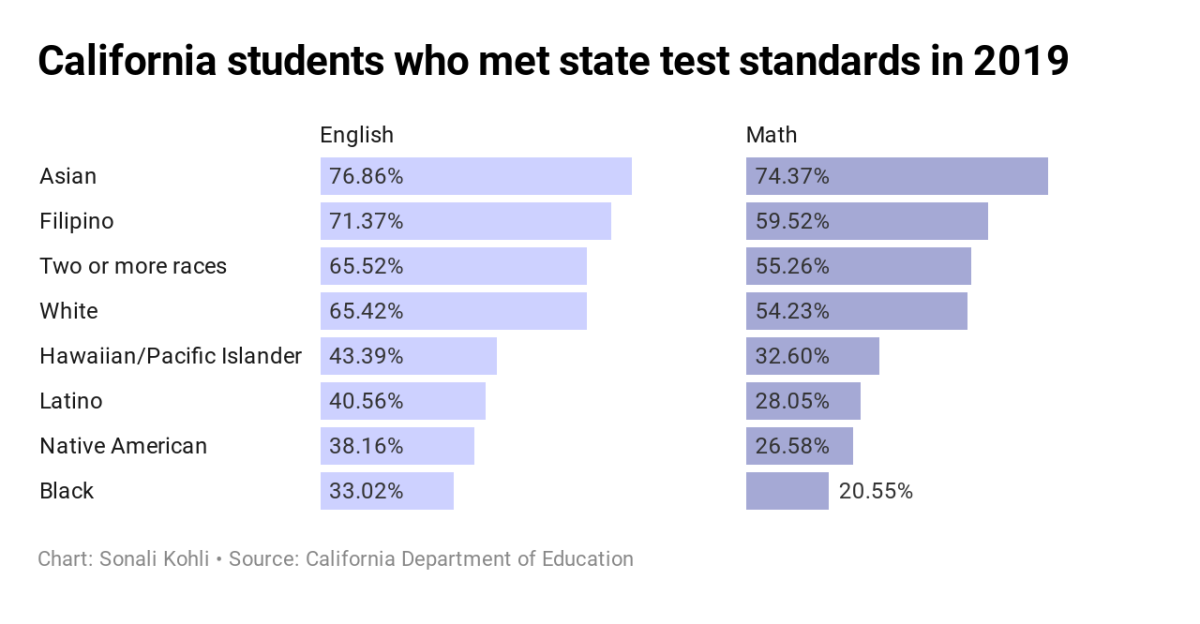

Black students are the furthest behind, with about 20.55% meeting math standards and 33% meeting English throughout California. The Los Angeles scores are slightly lower with about 20% meeting math standards and 31.95% meeting English.

“A concentrated focus on the needs of African American students” is an imperative in public education, said the L.A. Unified School District’s interim chief academic officer, Alison Yoshimoto-Towery, who added that the district is pursuing partnerships across the community, with local and state governments and higher education.

The district has rolled out a program called the Academic English Mastery Program at 110 schools with the highest concentration of black students, Yoshimoto-Towery said. The goal of the program is to target students for whom English is their first language, but the English spoken at home may be different from the “academic English” that exists in schools and on tests, she said.

These schools have additional professional development for teachers and principals, are using teaching strategies that are culturally relevant and are working with UCLA to assess children’s academic language “and then use that to drive instruction just like we do ... for English learners,” Yoshimoto-Towery said.

The state test results coincide with a new UCLA report that highlights the educational, health and environmental outcomes that contribute to lower academic outcomes for African American youth in Los Angeles County.

“The kids that are doing the least well and the schools that are doing the least well show an accumulation of disadvantages. They have the highest asthma rates, they have the highest homeless rates, number of kids in foster care, etc.,” said Noguera, one of the report’s co-authors.

One goal of the UCLA report is to provide data to support state and federal legislation that would address needs outside the classroom to improve student achievement, said UCLA professor and report co-author Tyrone Howard.

“Schools cannot be expected to solve this alone,” Howard said.

To do that, he said, lawmakers will have to overcome the discomfort of targeting resources to a specific ethnic or racial group, and instead treat students who are not meeting standards like any other group that needs additional help.

California’s school funding formula gives additional money to districts for students who are low-income, English learners or foster youth, but not for two groups who perform particularly low on the state tests: black students and students with disabilities.

“There’s got to be something kind of intentional for black students,” Howard said.

In a news release, state Supt. of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond said he is working with data experts to further evaluate and understand the scores.

“The CDE can work with all educational stakeholders to identify strategies and then explore legislative efforts to support the needs of local districts and provide resources to improve test scores,” he said.

The scores show that students with disabilities are also in need of better instruction, said Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the California State Board of Education.

“We’re continuing to make slow progress and steady progress, so that’s a good thing in a sense, but we still have some major problems and hurdles to deal with,” she said.

A statewide teacher shortage means that half of new math teachers and two-thirds of new special education teachers enter classrooms without complete training.

“We have a lot of people in classrooms that are not prepared to teach,” she said. “The biggest number of them have emergency credentials, which means they’re not in any kind of program.”

These teachers are most concentrated in the schools with high rates of poverty and a concentration of black and Latino students, and they tend to have higher rates of turnover, which negatively affects students, Darling-Hammond said.

“When they leave,” she said, “the professional development walks out the door with them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.