The terrifying experience of escaping wildfire with the power shut off: ‘It was pitch black’

- Share via

Mary and Charles Lindsey went to sleep to the glow of the Tick fire, but they had seen wildfires before, and their two-story home in the Santa Clarita foothills seemed safe enough. All Thursday, they hadn’t gotten a reverse-911 alert, or an emergency email, or a phone call. All had seemed quiet since 11 a.m., when Southern California Edison shut off their power.

It wasn’t until 2:30 a.m. Friday that something — maybe the whir of helicopters or perhaps the providence of God — woke Mary up. She saw the unusual light creeping through the bedroom curtains. “That’s not right,” she thought, grabbing a flashlight.

Outside, a sheriff’s deputy cruising by noticed the flashlight in the window and flicked on his siren, then shouted into the home: “It’s a mandatory evacuation!” The deputy wondered why the occupants hadn’t gotten an alert. She told him that entire section of the Stonecrest community didn’t have a clue. They were all still in their homes. “Oh, my God!” the deputy replied.

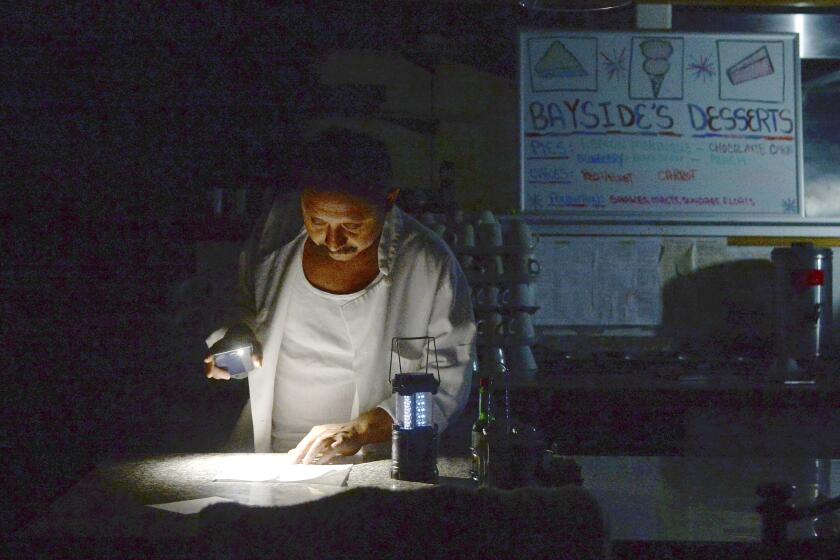

What followed, by Mary Lindsey’s recollection the next day at an evacuation center at the College of the Canyons in Valencia, was a pitch-black rush to safety for the Lindseys and dozens of their neighbors — just a microcosm of the unsettling new abnormal confronting residents in California’s sprawling wildfire country: managing emergency evacuations without lights, electrical garage doors, internet-enabled phone lines or air conditioning.

In the Lindseys’ case, it was too smoky to open any windows. When they finally evacuated during the dark morning hours Friday, Mary Lindsey had to reach under the bed for the flashlight she’d stashed there. She also put an extra one in her purse.

“It was pitch black,” she said. “Pitch black.”

The Tick fire was pushing toward homes in Santa Clarita, thanks to winds of nearly 30 mph and humidity hovering around just 6%.

As fires still raged in Northern California’s wine country and close to the suburbs above the 14 Freeway in Southern California, evacuees described how getting out, and getting on, felt markedly more frightening because the state’s biggest utilities had cut power as part of wide “public safety power shut-offs.” There was no small irony in the fact that the discomfiting power outages had been ordered to prevent the fires in the first place.

California has built much of its emergency response system around the premise that alerts and evacuation orders will be received by residents with cellphones or landlines. But landline technology has changed, and telecommunications companies are increasingly relying on internet technology, which is subject to power outages, to serve households with voice calls.

Utilities say they are working to address such challenges. A spokesman for Southern California Edison said a “critical-care customer” program offers advance warning to people who need further assistance in the event of an outage. But it’s unclear whether most customers in need of such service are aware that the program is available, or whether the warning time is enough.

Phil Herrington, Edison’s senior vice president of transmission and distribution, said the utility tries to give customers 24 to 48 hours’ advance notice of outages. “That gives customers time to make preparations — if they’re going to be out of communication, to identify other sources of communication,” he said. “We’re doing this for public safety, keeping in mind the trade-off.”

Asked about the evacuation challenges, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department did not respond to specific questions but issued a general statement: “There were several evacuation areas just south of the fire’s flash point,” the statement said. “In instances where there is a a fast-moving fire, no one method of emergent notifications can cover the need for public safety.”

Even before this week’s fires, Californians have learned the difficulties of getting out without electricity.

Janice Bell, a Chatsworth resident who has multiple sclerosis, had to get out of her Porter Ranch home in a hurry in the predawn darkness Oct. 14 because of the Saddleridge fire. But Bell’s car was trapped inside her garage, behind an electric door, and she could not open it. After two hours of waiting, she flagged down a neighbor who helped her open the garage door, and she drove to her office in Woodland Hills.

Bell said she received no advance notice of the power outage. And she said there would have been no way of learning from Edison’s website, which had been down for two days.

“It was just crazy to me that that can be allowed to happen…. I guess they never thought of people getting their garage doors open,” she said.

One key to getting through any emergency situation is preparation.

Evacuations were particularly complicated at the Isis Oasis, an animal sanctuary in the Sonoma County wine country town of Geyserville, where operators had to exit with an array of exotic creatures. Stumbling through a darkened pen, deTraci Regula tried to secure two emus, aggressive 5-foot-tall birds.

“Just as we began to evacuate, all the power went out,” Regula said, adding that a warning from Pacific Gas & Electric Co. about a shut-off had been canceled earlier. “We didn’t know that we were going to have one.” She said the darkness “pretty much doubled the effort…. We literally could not see what we were doing, and there was heavy ash.”

In Southern California, an evacuee at the College of the Canyons, Judy Intenso, had faced an Edison power outage at her apartment a week ago. Though there was no fire emergency then, she recalled the difficulty feeling her way to the door, where she stores a battery-operated flashlight.

She couldn’t imagine the stress of dealing with a loss of power with flames approaching. “To try to gather your things and your dog, and do all that in the dark without hurting yourself,” she said, trailing off. “Very scary.”

Millions of Californians can do little more than watch as the lights go off, then on and maybe back off again during the blustery autumn of 2019.

So, knowing she might lose power Thursday, Intenso prepared for the worst. When she got home, Intenso, an electrical technician, parked outside her garage, knowing that she would need electricity to open the door. She also filled up her gas tank, knowing that she’d want to leave her car running so she could use it to charge her cellphone. She got away cleanly and seemed to be coping well at the evacuation center, where she was joined by her adult son.

The fear of lost homes and possessions loomed large for many at evacuation centers. It came with an abiding anxiety for many — fear of running out of power for their mobile phones.

Outside the College of the Canyons on Friday, one evacuee sat under a blazing sun, where a Red Cross volunteer suggested he’d be more comfortable in the shade.

The man pointed to an electrical outlet and said, “I need juice.”

Times staff writers Phil Willon, Anita Chabria, Joe Serna and Colleen Shalby contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.