For ICE, business as usual is never business as usual in era of Trump

- Share via

The ICE agents had done their homework before they descended on their first target. They learned the 65-year-old Mexican man’s routines.

The agents weren’t sure where he lived, but they knew that almost every day after 4 a.m. he would appear from the predawn darkness to check on two trucks he parked in downtown Los Angeles.

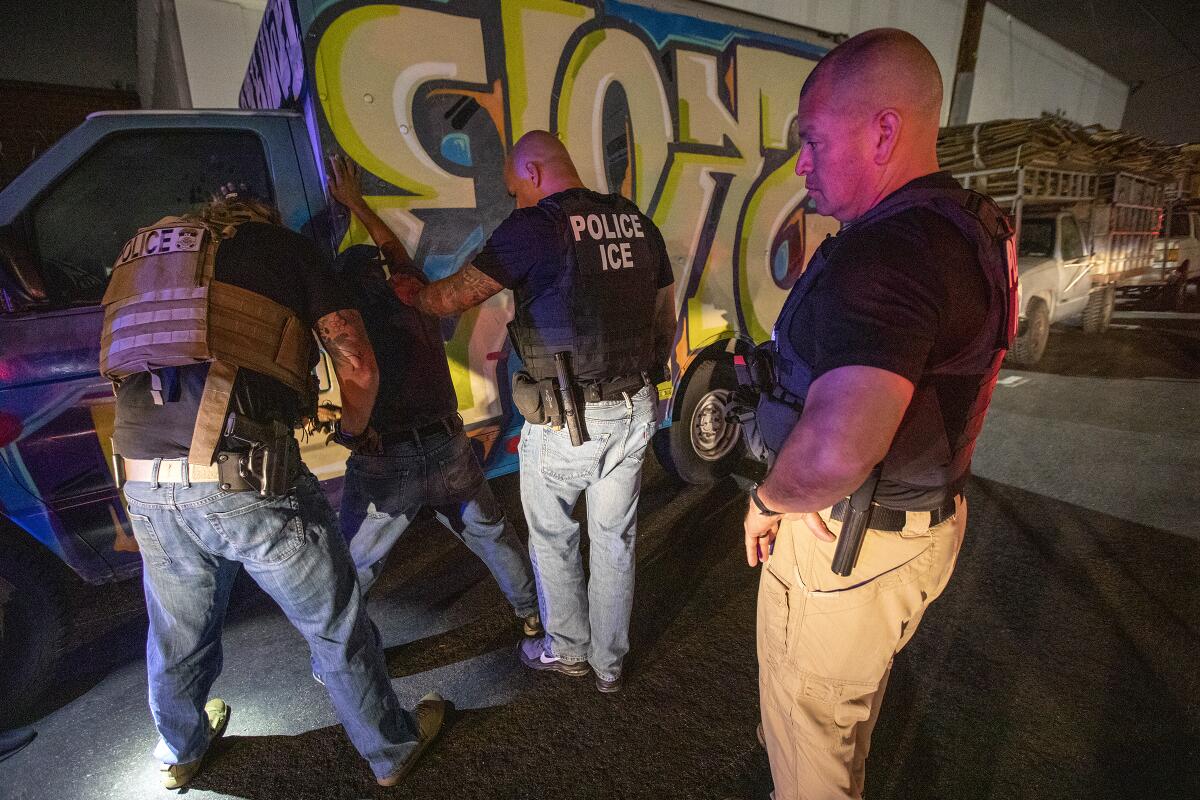

So the agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement sat in their unmarked vehicles and waited. Around 4:40 a.m., a man in a baseball cap and jeans emerged from a nearby street.

“He’s about ready to cross the street,” one agent called over the radio.

Moments later, the agents pulled up in four vehicles with flashing lights, startling the man. They patted him down, handcuffed him and quickly, without fanfare, took him away.

The man was arrested in August on suspicion of driving under the influence. ICE issued a detainer so that he could be held and retrieved, but the Los Angeles Police Department ignored it, said David Marin, the director of enforcement and removal operations for ICE in L.A. The man had been deported at least three times before, according to ICE, and had been arrested in the past, including more than a decade ago for assault, which resulted in prison time.

Americans hold sharply divergent views of ICE. Some support the controversial agency’s crackdown on illegal immigration. Others, angered by tactics they find excessive and even unconstitutional, want it abolished.

Large-scale ICE operations, such as the recent one in a Mississippi meat-processing plant where 680 workers were rounded up, have become a kind of reality-TV street theater that dramatizes the high stakes involved. But arrests such as the one of the Mexican national last month are the daily bread of ICE enforcement actions, Marin said.

“This isn’t anything special,” Marin said. “Our guys do this every day. This is their job.”

The numbers bear out that deportations and removals resulting from operations such as these have dipped under President Trump than they did under the Obama era, despite the blustering rhetoric and take-no-prisoners policies of the current administration.

The Trump administration is on track to remove about 8% more foreigners in fiscal year 2019 than President Obama did during his final year in office, according to ICE data.

But during the height of deportations under Obama, in 2012, immigration officials removed 409,849 foreigners. By comparison, peak removals under Trump occurred this year, with 257,000 as of Sept. 21 — a few days shy of the close of this fiscal year.

Some of the decline in removals and deportations can be attributed to less cooperation from local law enforcement, said Louis DeSipio, a political science professor at UC Irvine.

Many local law enforcement agencies — particularly in progressive states such as California — are no longer collaborating with ICE in the same way that they did under Obama, he said.

That has made it harder for federal authorities to apprehend some immigrants.

ICE agents have become so maligned that Homeland Security Investigations, a branch within the agency that focuses on combating cross-border criminal activity — billed as the investigative arm of the Department of Homeland Security — has sought to disassociate itself from ICE.

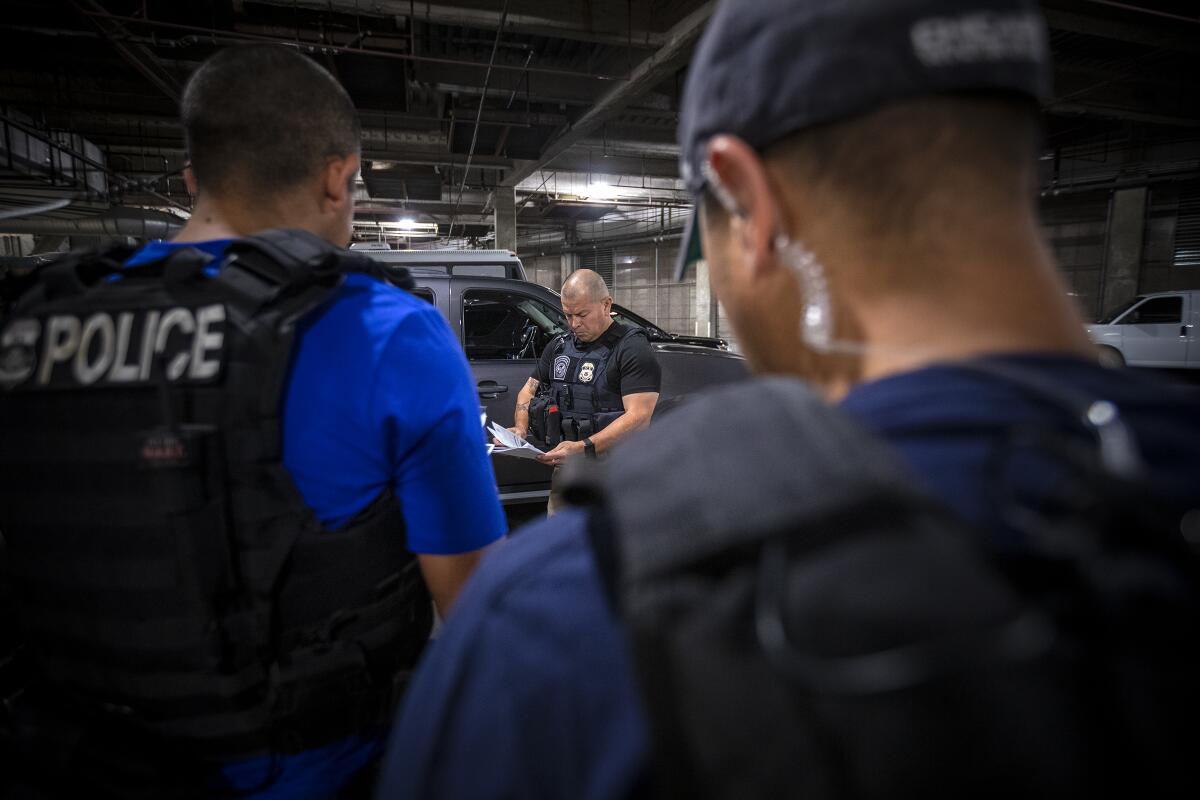

Every day, an estimated 100 ICE fugitive operations teams fan out nationwide.

In Southern California, 12 teams hit the streets every day across seven counties — from Los Angeles to San Luis Obispo. This is an area that spans 19,000 square miles with 19.6 million inhabitants.

“You’re talking about 75 guys to cover all that area,” Marin said. “I have a limited number of officers.”

The first fugitive operations team launched in Los Angeles in 1996 and expanded from there, said Marin, who started work in 1995 with what was then called the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

“As someone who has been doing this for 24 years now and who has been through numerous administrations, I’m still doing my job,” Marin said. “Policies and priorities always changed, but the laws never change.”

ICE fugitive operations target specific immigrants who are suspected of living in the country without legal status. Each target takes several days of surveillance before agents make that one apprehension.

Despite the rhetoric emanating from the White House and the backlash that inevitably follows, Marin insists that ICE’s targeted sweeps are no different in size or scope from operations it carried out in years past under previous administrations — both Republican and Democrat.

“Immigration has always been political, right? I have seen the pendulum swing to both sides, but in the past few years ... it just seems that it has become so much more controversial,” Marin said.

During the last couple of years, ICE has ignited widespread condemnation for its role in the Trump administration’s tough immigration policies.

The outrage is so dramatic that ICE is now the least popular federal agency in America, according to a Pew Research Center survey released last month. An estimated 54% view ICE unfavorably and 42% view it favorably.

Even though U.S. Customs and Border Protection is the agency responsible for implementing Trump’s border policy, the public doesn’t necessarily distinguish between both agencies.

Protesters have rallied across the U.S., demanding that ICE be abolished — calls that have been echoed by several left-leaning politicians. Across the nation, protesters have unfurled banners with the phrase “ABOLISH ICE” over freeway overpasses and famous landmarks.

In July, a 69-year-old man armed with a rifle attacked the Tacoma Northwest Detention Center in Washington, throwing incendiary devices at the immigration jail.

Last year, California’s “sanctuary” law, Senate Bill 54, went into effect, protecting immigrants in the country without legal status.

The Los Angeles Police Department stopped engaging in joint operations with ICE that directly involve civil immigration enforcement. The department no longer transfers people with certain minor criminal convictions to ICE custody.

The LAPD also generally ignores ICE requests to notify the agency when an immigrant is released from custody. Many of these immigrants then end up on a list of targets for the fugitive operations teams.

The majority of those targeted have been arrested on suspicion of or convicted of driving under the influence. But many others are targeted for relatively small and nonviolent offenses, such as multiple illegal reentries into the U.S. Entering the country without permission is a misdemeanor but can become a federal offense after a removal or deportation.

That was the story behind the agents’ second target, a homeless Mexican man in the South L.A. area. The 43-year-old lived in a van stationed in the parking lot of a Food 4 Less.

He had been removed from the U.S. three times. He had multiple DUI convictions — the most recent in February. The LAPD ignored at least one ICE detainer for the man, Marin said. Los Angeles County Jail ignored a detainer, too.

About 5:30 a.m., agents knocked on the van’s window.

“Open the door. Police,” an agent yelled out.

Bleary eyed, the man squinted and rolled down the window.

“What’s your name?” one of the agents asked in Spanish. “What is your complete name?”

Looking a bit wobbly, with sweat drenching his face, the man climbed out of his van. The ICE agents patted him down, handcuffed him and took him away. It took less than 10 minutes.

Marin said most arrests happen peacefully, but a growing number involve targets who fight back or try to run away. In some cases, he said, neighbors of people being arrested angrily confront ICE agents.

“In the last couple of years we have had people actively resist, and we never had that before,” he said. “People are a little more defiant.”

When Marin first started as a young immigration agent, it wasn’t unusual for him and other agents to pile into a van, pull up to a day labor site and catch up to 50 people they suspected were in the country illegally, he said.

“We’d process them and send them back, and I’d arrest that same guy two or three weeks later. It wasn’t an effective use of our resources. We don’t do that anymore. Not only because we don’t have the resources, but number one, it’s not effective,” he said. “These are targeted enforcement operations.”

Standing in the Food 4 Less parking lot, surrounded by agents with vests inscribed with ICE and POLICE, Marin said he wouldn’t be surprised if someone got on social media and the news got out: “ICE is raiding a Food 4 Less.”

It has become increasingly difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction, particularly in the region’s immigrant communities where false information about “raids” can spread quickly, causing unnecessary fear.

Though Marin and other agency officials say they are targeting immigrants with a criminal past or repeated removals, Trump has often condemned and lumped together all immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Trump has also tipped off ICE operations and his hard-line immigration tweets have arguably made it more difficult for the agency, experts say.

About a block away from the supermarket, the agents waited for more than a half hour for their third target: Osman Danilo Calderon, a 34-year-old Salvadoran man.

The father of three boys had clandestinely crossed into the U.S. twice. The second time he was deported was in 2009, following a conviction on driving under the influence. He appeared to avoid trouble with the law for almost 10 years, but then in March and June of 2018 he was arrested on suspicion of a DUI, according to ICE records.

L.A. police and L.A. County Jail officials ignored ICE detainers for Calderon, Marin said.

The immigrant, who paints homes for a living, said he was in the last few months of a sobriety program when ICE agents caught up with him.

Calderon pursed his lips, rubbed his neck and tried to hold back tears when he spoke to his mother-in-law by phone.

“Oh, God. For the love of God. What are we going to do?” the woman asked.

“Please don’t tell the children,” he told her. “Please call an attorney.”

After the call, he tried to collect his thoughts.

“I’m upset with myself,” he said. “It’s my fault.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.