California fire season likely to last through December, with no rain in sight

- Share via

The sun was beginning to set on Halloween when a small fire began to glow on a hillside near Santa Paula. Within seconds — fanned by the most potent Santa Ana winds of the season — the blaze roared to life with immense speed, chewing through thousands of acres of bone-dry brush and eventually consuming homes.

Devastating fire weather that ushered in a flurry of blazes across the state last month helped the Maria fire, which charred nearly 10,000 acres in four days, earn the title of this year’s largest Southern California wildfire. However, experts caution the blaze may be a preview of what could be a long season of devastating fires amid gusty winds and dry conditions.

A report from the National Interagency Fire Center, released Friday, predicts a higher-than-normal chance for other large fires in Southern California through December, with a late start to the rainy season looking increasingly likely. In the northern part of the state, a weather pattern that “favors offshore winds occurring over fuel beds that are primed for burning” is also expected to lead to abnormally large fires through November, according to the report.

“This may be a long fall and winter across California for both the firefighting community and the general public in terms of coping with the threats of fires,” the report states. “The best thing citizens can do is to be fire wise. Now is the time to prepare for wildfires and to have a plan to be ready for wildfires if they arrive in your area.”

Predicting how severe the fire season could be in California comes down in large part to a race between the start of the rainy season and the Santa Ana winds: which one dominates and at what time of the year, said Bill Patzert, a retired climatologist for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

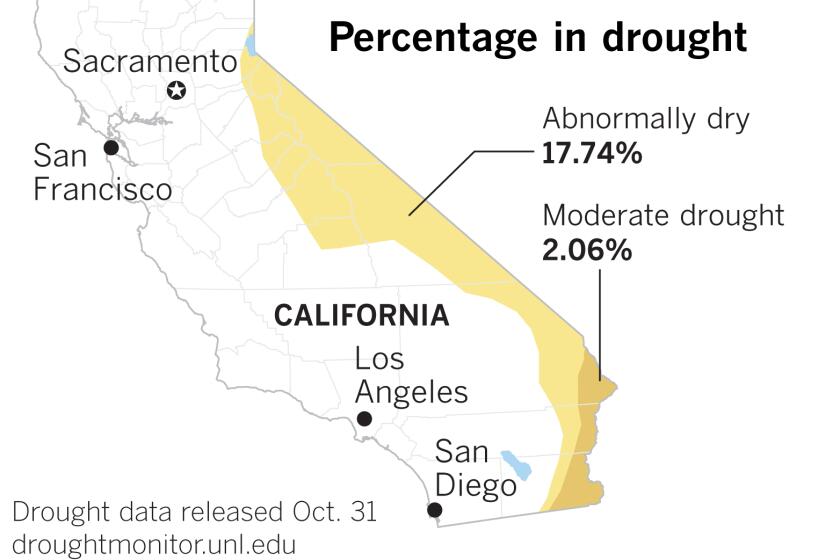

A good soaking across the state would dampen the fire season considerably, even amid strong wind events, he said. However, Southern California hasn’t had significant rain in seven months, and meteorologists say there’s no clear sign of rain anywhere in the forecast through at least mid-November.

What getting no rain in October means for the winter ahead in California

While October and November are not the state’s rainiest months, they’re especially important because when rains hit then, they reduce the fire risk from strong, dry Santa Ana and Diablo winds coming from Nevada and Utah toward the Pacific Ocean. Typically, October sees about six days of Santa Ana wind conditions, while November sees nine and December and January have 10 and 11, respectively. Diablo winds occur most frequently in October.

“The fire danger hasn’t diminished at all. In some ways, this is really the start of the beginning,” Patzert said. “Everything is pointing to more large fires here unless we get some rain.”

Last month’s severe winds also ushered in extremely dry air, leaving much of the state’s vegetation at near-critical dry levels. Several regions — including the southern Sierra Nevada, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Sacramento Valley and a sizable swath of the Southern California coast — have reached severely dry levels. Those parched fuels can help turn a spark into a raging inferno. Combined with strong winds, they can cast embers miles ahead of the body of large blazes, setting spot fires or engulfing homes and overwhelming firefighters.

“Californians think we are out of a drought, and we are, water-storage wise,” said Mike Mohler, deputy director of the California Fire and Forestry Protection Department, or Cal Fire. “But after years of persistent dry conditions, those dead fuels are still scattered across the landscape. And it only takes a 12-hour Santa Ana wind event to bring live fuels to critically dry levels.”

Santa Ana and Diablo winds have been part of California’s ecology since prehistoric times, experts say. But the fire risk to populated areas has risen as people have increasingly built homes and moved into wildlands particularly susceptible to wind-whipped fires.

In Southern California, more people live in Santa Ana wind corridors like the Santa Clara River Valley in Ventura County, south of the Cajon Pass in the Inland Empire and west of the San Gorgonio Pass east of Riverside, Patzert said.

California’s wildfire seasons are getting longer and more extreme, so the time to prepare is now.

In Northern California, North Bay residents living in homes built since the 1980s have been shocked to discover their risk from wildfires coming from embers flying in from mountains to the northeast, even though similar fires have burned through the region in prior decades. The 1964 Hanly fire carved a path of destruction nearly identical to the 2017 Tubbs fire, but because so many more people were living there in 2017, the Tubbs fire became the second most destructive wildfire in California history.

“We’ve built in a lot of places that we shouldn’t have built — but we continue to do that. And that needs to stop,” Hugh Safford, senior ecologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region, said. “There’s not a whole lot we can do about it, except not build homes in there, and it’s too late now.”

The strategy now is to avoid ignition, if possible, and evacuate people quickly when a fire breaks out.

“If you get a hurricane warning, you’re not going to sit around and wait to see what happens. You’re going to leave,” Mohler said. “We need to do the same thing here in the state of California. It’s not if, it’s when you’re going to be affected by a fire.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.