New boxing program in Watts seeks to show at-risk kids a different path

- Share via

Evana Catalan said bullies had been picking on her for a while at school, but the 9-year-old couldn’t do anything about it.

Her classmates, she said, would make fun of her for her nice demeanor and because she didn’t know how to fight. She felt sad and frustrated but couldn’t channel those feelings because she didn’t know what to do.

Then, on a Friday afternoon when she came home from school, things changed.

Her mother, Michelle Catalan, 27, told her about boxing classes that had just started at the Boys & Girls Club at the Nickerson Gardens public housing complex in Watts, where they live. Catalan said a friend told her about the program after she saw a flier hanging on her door. The friend encouraged her to come with Evana.

Now, after about two weeks of lessons, Evana said her confidence has already improved.

“When I came here and started doing the classes, it made me feel way better,” she said slowly in her high-pitched voice. “Now I know how to defend myself. It’s helped me out a lot.”

One of the goals of the Nickerson Gardens Boxing Academy is to encourage physical and mental toughness. But more important, organizers say, is its mission to show children a different path.

In a neighborhood that suffers from high crime rates and low incomes, academy leaders and parents say the program can show the youths that they don’t need to fall into a cycle of violence and hopelessness.

“When you’re able to have a program like this come into the community, it can help keep them away from all of the elements that don’t make it right for them,” said Donny Joubert, 59, an organizer of the academy who was raised in Nickerson Gardens. “We’re trying to teach our kids how to be responsible and do right. We knew if we could do this in this community, it would make a big difference.”

Every time Joubert sets up a training session, he is reminded of the people who did not have such an opportunity.

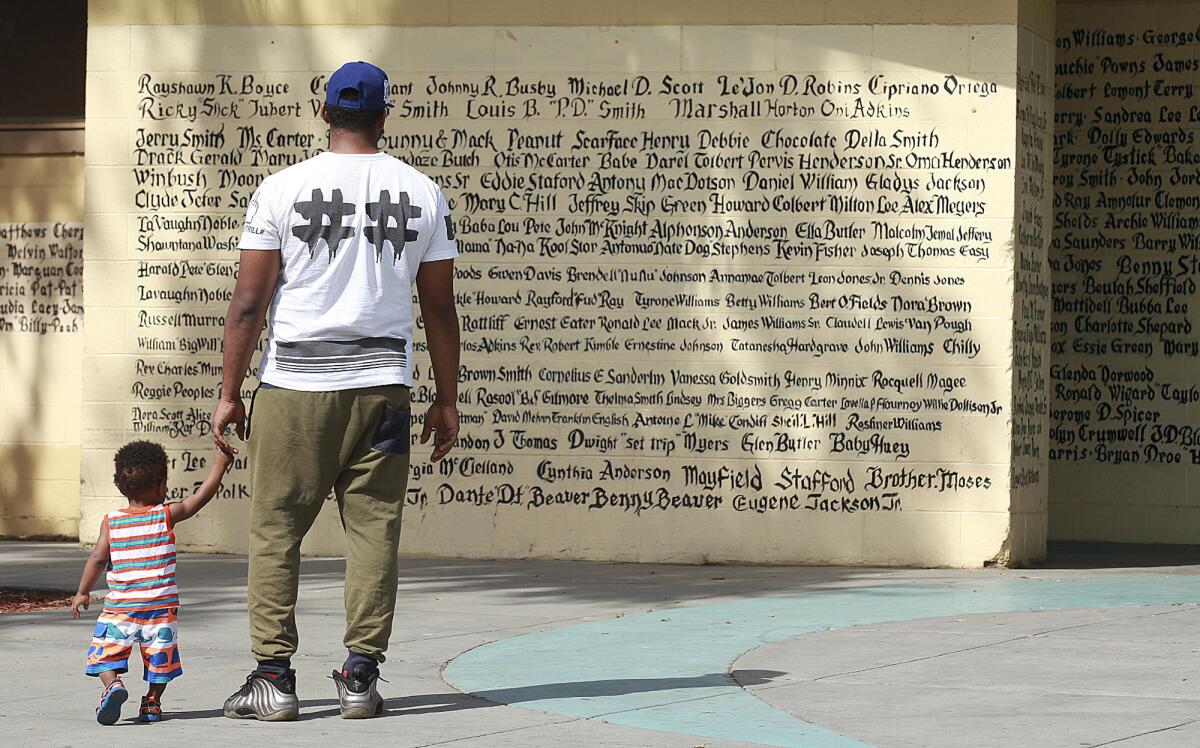

If you walk to the entrance of the Boys & Girls Club, you’ll be greeted with a yellow wall memorializing Nickerson Gardens’ dead. Scores of names painted in script handwriting symbolize those in the community who have died. Brian McLucas, 54, was born and raised in Nickerson Gardens. He helped spearhead the wall’s creation in the 1980s to keep the legacies of the fallen alive.

“So many people were dying and people wouldn’t even remember them,” McLucas said. “There were just so many deaths around here.”

Some were killed in gang-related incidents. Others died of natural causes. Regardless, residents view the wall as sacred. If you lean on it, a young child may “walk up on you and tell you to get off,” Joubert said.

Academic research suggests at-risk children suffer from a lack of confidence and social relationships. Watts ranks as the 11th-worst neighborhood for violent crimes per capita in Los Angeles, according to a Times analysis of crime reports. In the last six months, 217 aggravated assaults, 101 robberies, eight rapes and three homicides have been reported there, according to the Los Angeles Police Department.

Couple the violence with Watts’ median household income of just over $25,000, and those conditions produce ripe factors for children to get into trouble.

One night as Joubert and his friends worked out, they brainstormed ways to bring kids an escape. Boxing quickly came up. Similar initiatives had popped up in Chicago, Baltimore and other major cities. But in Nickerson Gardens it would be revolutionary, Joubert said.

“That’s one sport we never had in Watts,” said Joubert, a former gang member who now works with police to reduce tensions in the neighborhood. “Growing up as a young kid, they have a lot of energy, and to bring them into something like this and to give them the fundamentals, that’s something that’s never been done here.”

After gauging interest from children late in the fall, Joubert felt there was enough demand to actually pursue it. He and a few others scraped together $2,000 and approached the mayor’s Gang Reduction and Youth Development program with a grant proposal. The gang program then fronted the bill to purchase the equipment. It’s also paying for two trainers and two assistants.

Practices are free and held every weekday from 6-9 p.m. for anyone — children and parents — over the age of 7. On the Nov. 5 launch date, about 25 children and parents showed up. At a practice last week, about 60 participants came. More are added after each practice. Some newcomers trickle in after practice has started.

A typical night starts with them stretching outside behind the building next to the playground. Then they go to an upper room attached to the basketball court with black mats covering the hardwood floors. A trainer instructs them on basic boxing combinations against air opponents.

Eventually, Joubert hopes to build a two-story facility with enough equipment and space to support safe live-contact matches. But for now, they all line up to throw shadow punches and jabs at the trainer’s command.

Some wear athletic gear. Others come in the clothes they wore to school. Evana wore a striped dress, blue jeans and pink-and-white retro Air Jordan sneakers.

The staff hopes to hire more trainers and coaches, and buy better equipment. But an estimated budget shows they’d need at least $27,000 a year to make that happen. That would fully fund more equipment and coaches to meet the demand of the program’s growing number of participants.

“Nickerson has a hunger for new ideas and to keep the kids engaged,” said Tanya Dorsey, who oversees the administrative aspects of the program. “We know that this is in need, but we’re going to need more funding to keep it sustainable.”

For now, Joubert, Dorsey and the rest of their team make do with what they have. And so far, they think it is working.

Monica Moraloneli, 37, saw the flier on her door and brought her son, who has autism, with her. The program, she said, is important because she can be active with the rest of her neighborhood. It also sets a positive example for her son.

“I need to show my son to follow me,” she said. “If I can do it, he can do it. But I need to show him and be a role model.”

Nike Williams, 31, a single mother who has lived in Nickerson Gardens all her life, allows her two oldest children to go to the academy and has seen a change in her son’s behavior.

“He has the mother figure, but he doesn’t get the father figure at home,” Williams said. “When he comes here, he gets the father figure. A man’s sternness is different than mine, and that helps a lot in terms of discipline.”

McLucas, the memorial wall’s creator, applauded Joubert and his team for starting the academy. It’s a good thing for Watts, he said, and he hopes it will be in place for years to come — for Evana and everyone else who benefits from it.

“If you help our children lead a productive life, then that’s one less person you have to worry about,” McLucas said. “Everybody deserves a chance, and some of these kids over here have never had a chance. The more positivity we can present makes it less likely that these kids will be in the streets.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.