For families of those killed by deputies, a long wait for answers

- Share via

Sitting in the audience at a recent town hall meeting, Julie Diaz-Martinez held up a stack of papers to present to Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva.

It was a lawsuit, she told him, filed on behalf of families like hers whose relatives were killed by sheriff’s deputies. They were seeking records under SB 1421, the new transparency law that requires California law enforcement agencies to disclose previously confidential records related to police misconduct and serious uses of force.

Since the law went into effect on Jan. 1, the Sheriff’s Department has fielded thousands of records requests from members of the public, including news organizations and law enforcement watchdogs, causing a backlog that has delayed responses, the department said.

But the lawsuit, filed by the American Civil Liberties Union in Southern California, contends that the department has resisted releasing records, for example demanding that those seeking information provide specific details, such as the names of deputies.

Of requests to 400 law enforcement agencies under the California Public Records Act, the “LASD is the only agency in the state of California to deny the ACLU’s request in its entirety by asserting that the request was ‘too broad in scope’ and that it was unable to produce responsive records,” the lawsuit said.

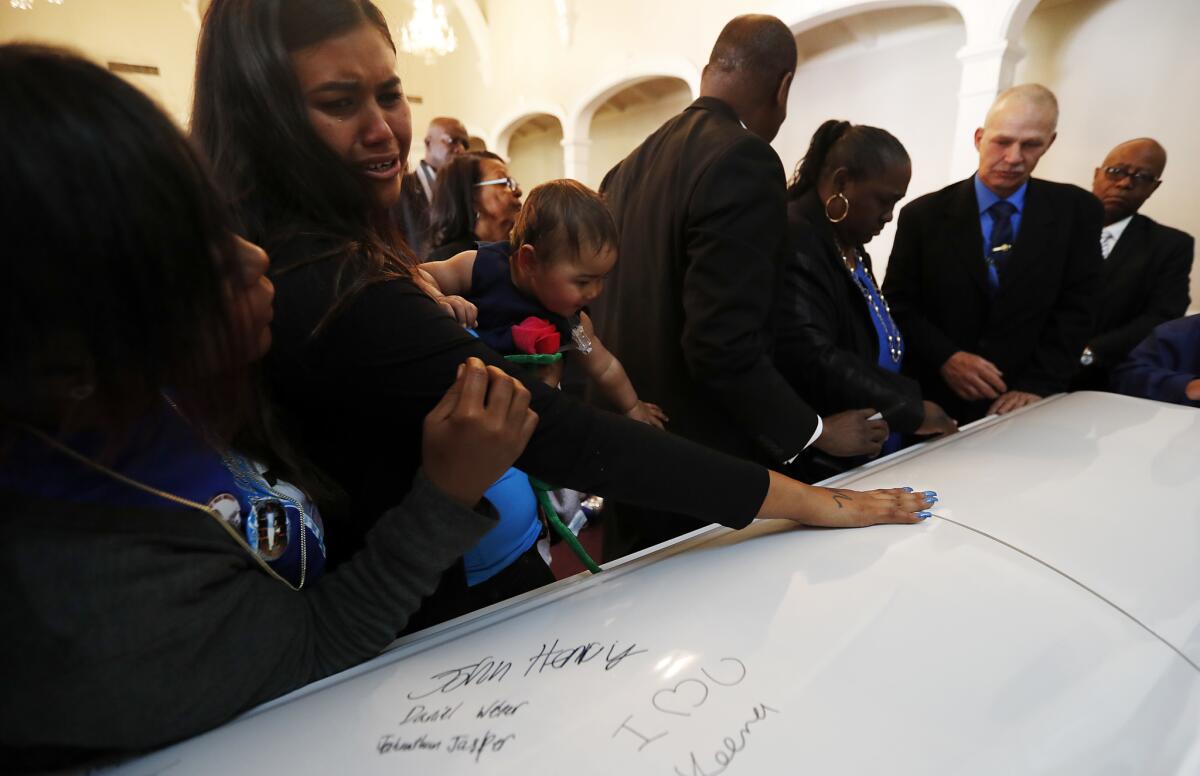

The delays have been particularly difficult for families seeking to piece together details about fatal encounters and any disciplinary actions of the deputies involved.

“It’s not giving me any type of closure,” said Demetra Johnson, whose 16-year-old son, Anthony Weber, was shot and killed in February of last year.

In March, Johnson requested all records relating to the investigation into her son’s death. The Sheriff’s Department said deputies saw a gun in the teen’s waistband, but no gun was recovered from the scene. She told The Times she has yet to receive any documents but hopes they will provide answers.

“I’m hoping it shows exactly what happened,” said Johnson, one of three plaintiffs named in the lawsuit. “I’m also wanting to know: Has this officer done it before? Has he done it since? And if so, we need to hold this man accountable.”

Villanueva told the town hall audience that his agency has produced more than 1,400 records since the bill became law, but still has a backlog of about 3,300 requests. It’s unclear how many of the 1,400 he referenced are in direct response to SB 1421 requests. He said he’s sought funding from the Board of Supervisors for 11 additional staff members as well as redaction software to facilitate the requests.

“I’m hoping that by the end of the year, we’ll have got at least to the halfway point,” Villanueva said. “And we’ll pick up the pace, as we get more people trained on this … From 2018 to 2019, the demand has grown probably over 5,000%.”

He suggested that the lawsuit was premature and refused to allow Diaz-Martinez to serve him the papers. Diaz-Martinez isn’t a plaintiff in the lawsuit filed by the ACLU, which was a sponsor of SB 1421, but she lost her grandson, Paul Rea, in a deputy-involved shooting in June.

“You can serve it the right way — not here,” Villanueva told her.

In a statement, the Sheriff’s Department said it is “working diligently to satisfy a major unfunded mandate” from the Legislature.

“Our budget mitigation efforts have left us with an insufficient capacity to handle the deluge of thousands of PRA SB 1421 requests for documents. Unfortunately, funding to date for sufficient personnel and equipment to meet these demands has yet to be received,” the statement said.

A county spokesperson said the department received five positions in the 2018-19 fiscal year to comply with SB 1421 requests. And this fiscal year, the department received $512,000 to fund an attorney and paralegal, as well as more than $200,000 to fund overtime costs, to help the department get through requests more quickly.

Johnson’s son was shot one evening last year when two deputies responded to a report of a young man in blue jeans and a black shirt pointing a handgun at a driver in the 1200 block of West 107th Street, authorities said. The driver, according to partial audio of the dispatch call, said he feared for his life.

While on foot, deputies encountered a 16-year-old boy who matched the suspect’s description. They spotted a handgun tucked in his pants, according to statements by the Sheriff’s Department.

When they ordered him not to move, the teen took off running into an apartment complex known as a gang hangout, authorities have said. After entering a courtyard, he turned toward the deputies and one of them fired about 10 shots. Neighbors quickly flooded the courtyard. No weapon was found. Authorities asserted that the gun went missing during the commotion.

Johnson called that allegation ridiculous, saying her son was unarmed. Anthony’s killing sparked weeks of protests in South Los Angeles, and county leaders settled a lawsuit brought by his family for $3.75 million.

“I want it to be known although my son was not the perfect child, at that moment in time he did nothing wrong to warrant getting killed like that,” Johnson said.

Since Anthony was killed, Johnson said she won’t allow her 13-year-old son to walk to school. When her 19-year-old in the U.S. Army is home visiting, she makes him take an Uber to the library, seven blocks away.

“It used to be the police, that I feel like they were some form of protection,” Johnson said. “But now I don’t feel like my sons have any type of protection.”

Vinly Eng lost his sister, Jazmyne Eng, in 2012 when Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies responded to a report that the 40-year-old woman was holding a hammer in the lobby of the Asian Pacific Family Center.

When she did not respond to instructions to drop the hammer, deputies attempted to shoot her with a Taser. Deputies said the woman raised the hammer and began to advance on one deputy. The deputy’s partner fired his gun, hitting her in the chest.

In May, Eng, one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, sought records available under SB 1421 related to the four deputies who responded to the call. The lawsuit says that within 12 seconds of making visual contact with the woman, one deputy fired his Taser at her and another shot her.

They were disciplined for rushing their actions and failing to make sound tactical decisions when the woman was undergoing a mental health crisis, according to a county oversight report issued in 2013.

“All families should be informed to the fullest extent about how officers are held accountable for actions that take the life of another, especially when a review has deemed that the actions were out of protocol, as with my sister’s case. Knowing this information is important for advancing justice for Jazmyne, for healing my family,” Eng said by email.

Zachary Wade sought similar records related to the killing of his 21-year-old nephew Nephi Arreguin, who was shot by a sheriff’s deputy in May 2015 while in his car in Cerritos. County officials have said that Arreguin disobeyed commands and struck the deputy with his vehicle.

“Even today, this day, after all these years, I still haven’t received any information,” Wade said. He later added: “When you ask questions about it, no one wants to give you answers. They want to be hush-hush. Of course that is definitely retraumatizing.”

L.A. County settled lawsuits brought by families of Eng and Arreguin. In both cases, the L.A. County district attorney’s office concluded that each deputy acted in lawful self-defense when they used deadly force.

The Times is part of a coalition of 40 news organizations called the California Reporting Project, which is gathering and analyzing records released under SB 1421.

The Office of the Inspector General, which provides oversight of the Sheriff’s Department, has also complained about a lack of transparency under Villanueva. According to a report the office published in August, numerous public record requests under SB 1421 had gone completely unanswered.

The report also said the Sheriff’s Department has blocked the inspector general from reviewing employment packages, including background checks and polygraph tests, of candidates for deputy positions, raising concerns that hiring standards have been relaxed to increase the applicant pool.

Inspector General Max Huntsman told the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission recently that he has not received a response from the Sheriff’s Department about the report since it was published.

“The only response we’ve ever gotten is what you just heard, which is: ‘If you’ll only tell us what we haven’t given you, we’d be happy to work that out,’” he said. “I don’t know what more I can do than put it in a public report on a public website.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.