One of California’s most powerful labor unions is feuding with Gov. Gavin Newsom

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — A young girl dressed as a newsie walked up to Gov. Gavin Newsom at the California Democratic Party convention in Long Beach last month, handing him a copy of a paper with his image splashed across the front page.

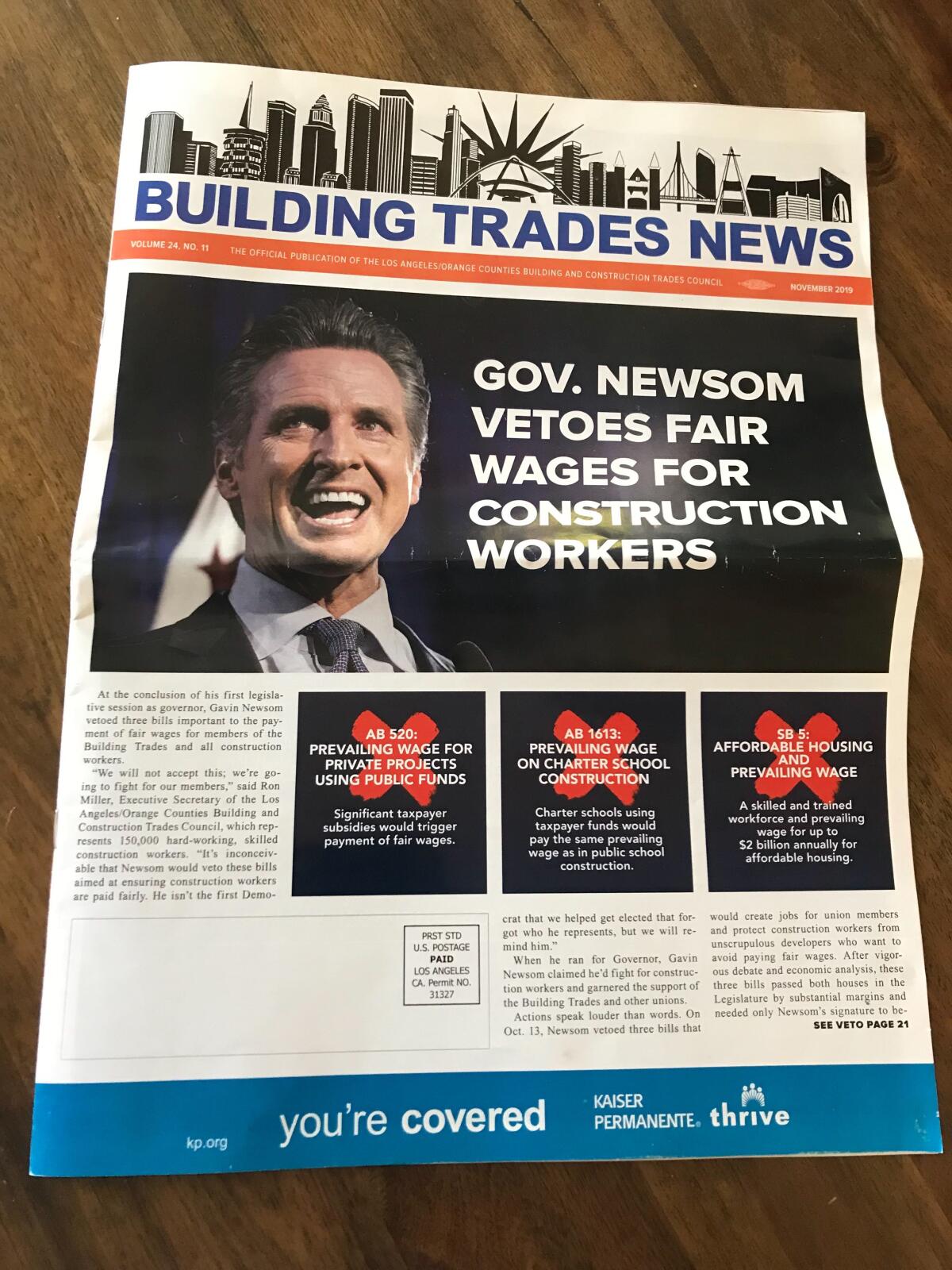

Alongside an unflattering photo of the Democratic governor, a headline on the Building Trades News read: “Gov. Newsom Vetoes Fair Wages for Construction Workers.”

The State Building and Construction Trades Council of California, which represents plumbers, electricians, ironworkers and other construction workers, distributed hundreds of copies of the anti-Newsom story at the convention, escalating an increasingly public and personal feud with the governor on the state party’s biggest stage.

“They’ve been doing it for months,” Newsom said later. “Honestly, it didn’t surprise me.”

As the end of his first year in office nears, the governor has found himself on the wrong side of one of the most formidable factions of organized labor at the Capitol in a fight that could threaten his agenda to address the state’s housing crisis and test the trades’ political muscle in Sacramento. The 450,000-member union is a major Democratic donor and one of the most influential players on housing issues in the state.

Tensions brewed for nearly a year, fueled by what the union says were actions by the governor that ran counter to the interests of its members, including vetoing bills they supported. But some in the labor movement say it comes as no surprise that the trades — known for commanding respect and pulling no punches with officials — are the first among them to publicly quarrel with Newsom, a governor who has championed a variety of causes backed by unions over the last 11 months.

Many in political circles are closely watching the battle as a case study that could inform their own strategies to address future differences with the governor.

“I’m only asking for hundreds of thousands of workers to be treated fairly,” said Robbie Hunter, the president of the trades. “It’s worth risking the scorn of this governor.”

Newsom says he doesn’t “fully understand” the feud. Without naming Hunter, he attributed it to “an individual or two that has some personality issues.”

“I’m really proud of the work we’ve done with labor, including the trades,” Newsom said. “And I have so many friends in the trades, within the trades.”

Hunter, a longtime Los Angeles ironworker and labor leader, has led the council since 2012. At his East Sacramento home last month, he answered the door with a feisty Norwich terrier named Finnegan tucked under his arm. The American Kennel Club says the breed embodies “the old cliché ‘a big dog in a small package.’” And so does Finnegan’s owner.

The brawny 62-year-old is a hard-charging straight-shooter who hails from a line of ironworkers in Belfast, a family Hunter said barely scraped by. Ask him who he is and his response, delivered in a thick Irish brogue, is always the same: “I’m an ironworker.”

Hunter said the trades initially became concerned about the new governor during his State of the State speech in February, when Newsom surprised Capitol observers by announcing his intention to scale back the ambitious high-speed rail project championed by his predecessor, Gov. Jerry Brown.

“The current project, as planned, would cost too much and respectfully take too long,” Newsom said, noting that “there simply isn’t a path to get from Sacramento to San Diego, let alone from San Francisco to L.A.”

The speech sent shockwaves through local union halls, with many workers worried about the fate of more than 50,000 construction jobs the project is expected to create. The governor and his advisors scrambled to clarify exactly what he intended to do.

Hunter said he read an early copy of the speech and advised Newsom to include language making his commitment to the full project clear, a suggestion he said was ignored. Some of Newsom’s other plans, including a downsized effort to build a new water delivery system through the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, similarly irked the trades.

Months later, the Newsom administration sought to include Hunter in a new commission tasked with mapping out a future for the state’s workforce that takes into consideration concerns including automation.

Hunter’s biography was approved in late August for a news release naming the commission’s members. But days before the administration announced the new commissioners on Aug. 30, a low-level Newsom aide told a lobbyist for the trade council that Hunter’s invitation had been revoked.

As one former legislator and friend of Hunter, who declined to be named, put it: “It was a huge slap in the face.”

Hunter was pulled from the commission at a particularly tense moment in the relationship between the trades and the Newsom administration.

That summer, labor leaders were locked in a battle with technology companies over Assembly Bill 5, which stood to rewrite California’s employment law and reclassify thousands of independent contractors as employees. Newsom’s administration asked union representatives to sit down with gig employers such as Uber and Lyft, and Hunter believes he was removed from the commission for refusing to support an exemption to the legislation for the ride-hailing companies. The trades took particular issue with gig employer Handy, which Hunter says provides some of the same types of work as his union members.

Some in labor said Hunter was a roadblock in the negotiations, a characterization he agrees with.

“I believe it was the building trades in the end that blocked a carve-out for the gig companies,” Hunter said, adding that they worked closely with the Teamsters union. “It got brutal.”

Those close to Hunter say his reasoning for resisting a deal is woven deep into the fabric of who he is and what he thinks is right for the men and women he represents. To explain his thinking, Hunter recounted a story his grandfather told him about competing for jobs building skyscrapers in Chicago during the Great Depression. The workers weren’t allowed to talk or offer one another safety warnings or they’d be replaced, he said.

“It was called ‘the shape-up,’” Hunter said. “These gig companies are the shape-up again, where you bid against each other and fist-fight each other. That’s what they did back then, to get the job of the day. That’s what we fought our way out of.”

Nathan Ballard, an advisor to Newsom during his days as San Francisco mayor, said the governor’s administration and labor leaders need to form relationships that allow them to disagree in private without problems blowing up in public.

“Every new administration has to find their own way, but one of the immutable principles is Democratic governors and organized labor have to have robust, healthy relationships,” Ballard said. “They can fight, they can argue, they can have policy disagreements. But ultimately they need to be in constant communication and that’s what all governors learn in their first term.”

The final straw for the trades came on Oct. 13, when Newsom vetoed three bills that would have increased the number of development projects paying union wages. Minutes before the governor’s office sent out a news release announcing the decision, Hunter issued a strongly worded statement that said Newsom disrespected the “contribution of blue-collar workers.”

“National politics provides us a cautionary tale of what happens when the working class is forgotten by candidates who are steeped in the ambitions of unrequited presidential aspirations,” he said. “California could, and should, do better for workers and their families.”

Hunter accuses Newsom of vetoing some of the bills as a favor to the California Building Industry Assn., which represents commercial developers and builders. The union boss says Newsom’s approach is starkly different from that of former Gov. Jerry Brown, who Hunter said respected the trades and offered a forum to explain what their bills would do for working people.

“I would explain what it would do and if I explained it well enough he would sign the bill, but he would always give us the opportunity to come in and sit down and explain,” Hunter said. He said the union’s lobbyists weren’t afforded those same opportunities this year, despite assurances by the Newsom administration.

The day after the vetoes, the trades began running social media ads that criticized Newsom for leaving a labor seat on the Occupational Safety and Health Appeals Board unfilled for months.

Last year, the trades took similar aim at Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, protesting outside the Getty House and blasting him in the Building Trades News over his Green New Deal for Los Angeles, which Hunter said would have eliminated union jobs at power plants and an oil refinery without providing feasible green alternatives. The trades eventually met with Garcetti and resolved the dispute.

The trades also ran a campaign in 2018 opposing the reelection of Assemblywoman Cristina Garcia (D-Bell Gardens). The union hammered Garcia over sexual harassment allegations made against her and said she was disrespectful to workers. In 2015, the union paid for ads against former Central Valley Republican Rep. Jeff Denham after he advocated defunding the high-speed rail project.

At the convention, Newsom said his administration has tried to sit down with the trades to work out the problem, but Hunter said that hasn’t happened since before the vetoes. Newsom pointed out that Brown vetoed a bill similar to one that the trades were upset about this year and downplayed the feud, saying that he has strong relationships with many in the trades and will continue to do what he thinks is right for working people.

“I’m not worried about it because if we fundamentally had different values, or saw the world completely differently, then it’s an issue,” Newsom said. “But because we legitimately don’t, I’m not worried about it any more than just a temporary distraction. And to the extent that one or two people have another agenda, we’ll have to work around that or through that or over it.”

Though currently strained, the relationship between Newsom and Hunter’s union is one of mutual benefit. The trades need the governor on their side to successfully push the interests of their workers, which often conflict with the goals of developers and sometimes clash with the objectives of environmentalists. And some say past lessons show the union is capable of blocking the governor’s housing agenda if they remain at odds. The trades helped quash Brown’s 2016 proposal to remove some local barriers to building more housing, saying it would have diminished their ability to weigh in during the approval process and advocate for their workers.

Ballard and others say it’s important that Newsom and the union resolve the high-stakes battle.

“My view is that peace needs to be made when both parties are ready,” Ballard said. “Gavin Newsom is too smart to hold a grudge for too long, and Robbie Hunter knows he’ll be more effective if he has a better working relationship with the governor.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.