He went from buffalo wings to cannabis and became the talk of L.A.’s marijuana industry

- Share via

As a businessman, Karim Webb won acclaim for opening a Buffalo Wild Wings restaurant in a stretch of South Los Angeles that other investors had avoided, bringing new jobs to the area.

He has been honored by Black Enterprise magazine, tapped to serve on charitable boards and praised effusively by L.A. leaders. When he was chosen as a city airport commissioner, Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson declared “there is no more stand-up citizen of our city.”

Now Webb has turned his focus to the contentious world of cannabis — and abruptly become the target of envy and suspicion as marijuana entrepreneurs compete for a limited number of L.A. licenses.

The reason: In the latest round of city approval, nearly a dozen of the applicants that have advanced past an initial step in the marijuana licensing process are partnering with his new company.

That number surprised some cannabis entrepreneurs, who have questioned how applicants assisted by his firm had secured so many coveted spots in the first-come, first-serve process to open new marijuana shops.

“It’s hard to swallow,” said Donnie Anderson, a founder of the California Minority Alliance, who said last week that none of the dozens of applicants his group worked with had fared as well. “We want to know how that happened.”

Webb, for his part, said he’s upset that applicants who partnered with his company didn’t do even better, saying his company helped 32 worthy applicants apply in this round of licensing. The more of their applicants who succeed, company officials said, the more people they can ultimately assist getting a foothold in cannabis and — eventually — other industries.

“This has never been about cannabis to me,” Webb said. “To me, this is about people, specifically the descendants of slaves, having the opportunity to live equitably in our country — to thrive.”

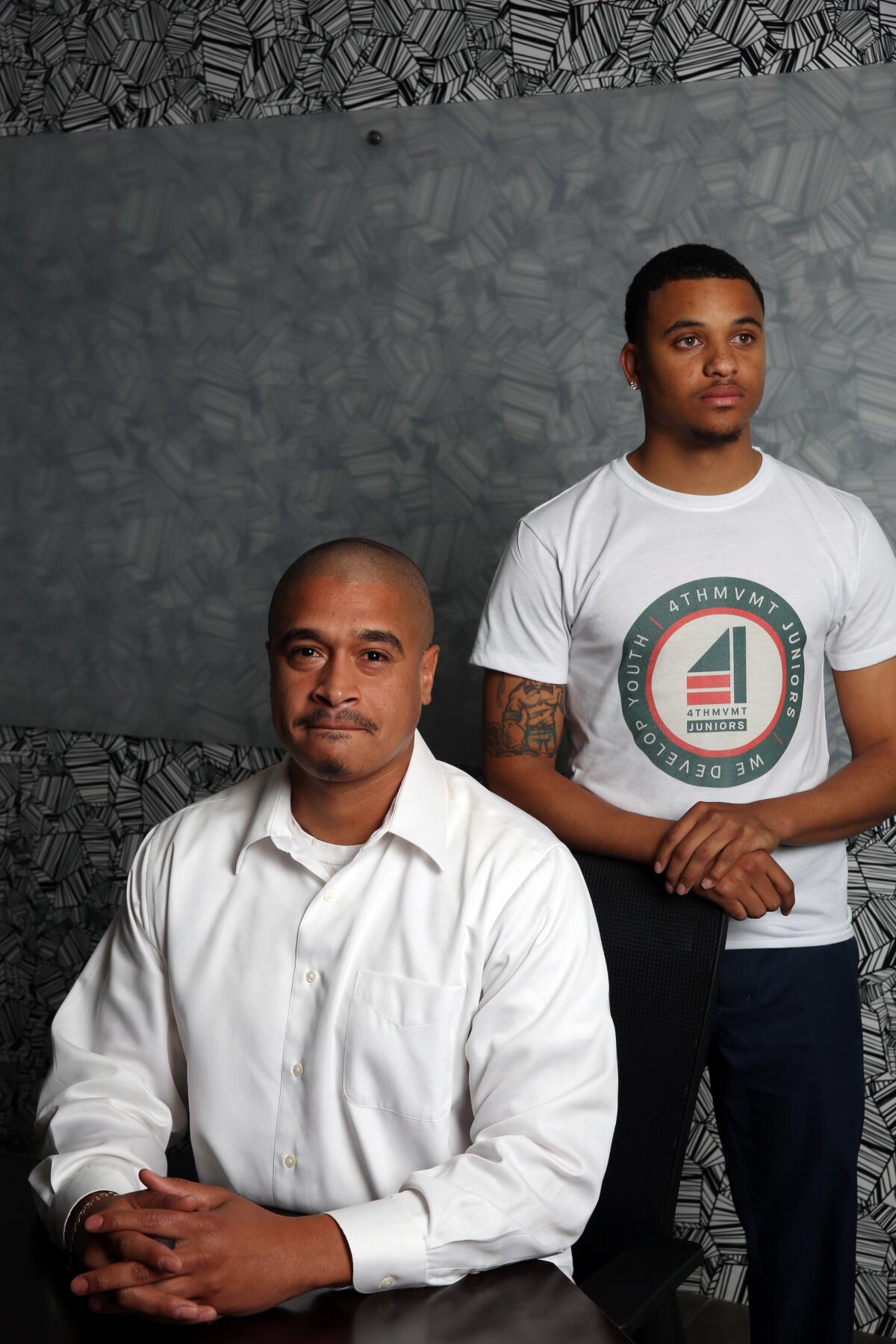

His company 4thMVMT — pronounced “Fourth Movement” and named for a famous reference to African American economic equality — assists candidates who qualify for L.A.’s social equity program, an initiative meant to benefit people from communities hit hardest by the war on drugs.

Anyone who applied for an L.A. marijuana license in the latest round had to qualify for the social equity program, but so far, the city has not provided all of the training that such applicants are supposed to receive under the program.

Webb said his company is dismantling barriers to business ownership by training and partnering with minority entrepreneurs, providing a range of assistance including business and management training and help securing leases and managing permits. His goal, he said, is to ensure that 4thMVMT applicants can not only win licenses but compete successfully against industry heavyweights like MedMen.

“They’re trying to get people who would never have the opportunity to own and operate a business ready” to do so, said 4thMVMT applicant Chris Bryant, who currently works for Enterprise Rent-a-Car and described himself as “a child of the war on drugs.”

Applicants like Bryant are vying for licenses in a furiously contested process: Hundreds of would-be businesses are clamoring for city approval, but Los Angeles is slated to approve only 100 new shops in the latest round of licensing, vetting them based on who turned in their applications fastest. Mere seconds made the difference in getting a top spot.

The process has been mired in controversy.

After the Department of Cannabis Regulation confirmed that two people had accidentally gotten into the application system ahead of time, critics argued that it had been fatally compromised. Some also pointed to the number of applicants with Armenian surnames, questioning how so many had qualified for “social equity.”

Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that the city would launch an independent review of the application process and hold off on “final licensing” until that audit was complete. In the meantime, the city is continuing to bill cannabis applicants with invoices for application fees if their paperwork meets some basic requirements.

As of late November, the Department of Cannabis Regulation had handed out 75 such documents to people seeking to open new shops, an initial step before their applications are vetted further. Eleven of them went to 4thMVMT applicants.

Webb is not the only businessman tied to several candidates who are advancing in the application process.

A Times review of business filings identified five linked to Kyle Suffolk, managing partner with Vantage Green Partners and a former MedMen employee. Suffolk said the applicants were not affiliated with MedMen and “we submitted our applications manually like everyone else.”

Other applicants may have financial ties that are not immediately apparent from state business filings. The Department of Cannabis Regulation declined to provide full applications to The Times, saying it was not its “policy.”

Kika Keith, a social equity applicant and founder of the advocacy group Life Development Group, said that “the number of applicants connected to big business concerns me” because they might have had technological advantages allowing them to submit applications faster. Others raised concerns about their neighborhoods having slower internet.

“That’s not a fair and equitable process if we have to leave our communities to even have a fair shot,” argued Sherri Franklin, one of the founders of GoVerde Incubator, which works with social equity applicants.

4thMVMT representatives said they submitted applications from South L.A. but also trained temp workers to swiftly type up applications, compressed files so that they would upload more quickly, and plugged into Ethernet instead of relying on Wi-Fi.

In every way, “we intend to be best in class,” Webb said. “You know, I think there’s an assumption that when you are an African American business, that you’re going to be uncompetitive.”

4thMVMT declined to provide a copy of a typical agreement between the company and its applicants, but representatives said the company gives its social equity applicants a much bigger share in each business — 81% — than the city requires.

Leimert Park resident Rhavin McSweaney, another one of its applicants, said 4thMVMT had given her a path to “generational wealth” for her family.

“It’s so much more than” opening a marijuana shop, said McSweaney, a new mother who has been working in television and film production. “It’s about people who don’t have access to those resources.”

Webb grew up in Rowland Heights as the son of McDonald’s franchise owners, attended Morehouse College and eventually launched Buffalo Wild Wings franchises. He has been a prominent player in philanthropic causes, including the California Community Foundation and the social services group Brotherhood Crusade.

The City Council does not have any power, under the licensing process, over whose applications are vetted first in this round. But some of the industry suspicion surrounding 4thMVMT has nonetheless focused on its City Hall ties.

In a presentation last year for potential investors, 4thMVMT included a slide touting that it was “uniquely positioned,” and featuring photos of council members. Company staffers said that presentation was outdated and was meant to tell venture capitalists unfamiliar with them that people knew about their “good work” and “reputation for doing the right thing.”

4thMVMT also employs a son of council President Herb Wesson, although it said his work focuses on governments other than Los Angeles.

Wesson, who has backed an audit of the approval process, reiterated in a statement that the council “has no influence on who gets selected for what” during this phase of the process. Webb likewise stated that any connections at City Hall didn’t give his applicants any advantage.

The latest round of cannabis licensing, the first for people seeking to open new shops in L.A., comes after the city has already granted approval to some existing shops and their suppliers. New operators will get another crack at licenses in a following round, which is likely to be just as intensely competitive.

“Too many more people want in on this than there are spots allowed,” said Adam Spiker, executive director of the cannabis industry group Southern California Coalition.

He summed up concerns he had heard: “Now everyone’s looking at this through the lens of, ‘Why didn’t I get a license? Why did this guy get 11? Why did two people get in early?’

“It just snowballed into a widespread belief that the process wasn’t on the up and up,” Spiker said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.