At this church, many see a divine image of the Virgin of Guadalupe written in concrete

- Share via

The parishioners at Holy Family Catholic Church in Artesia walked out into the chilly morning darkness to gawk at the puddle on the sidewalk.

Just minutes before, they had witnessed the spectacle that is the mañanitas Mass: plumed Aztec dancers and traditional hymns to celebrate the feast day of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico’s beloved patron saint.

Now, they stared at la jefa herself — not in the flesh, but in the concrete. For the faithful at this church, la virgencita herself shone in the stain beneath their feet.

And she has, they believe, for a year now.

It was last December, just after this same Mass, that Holy Family members say Guadalupe first graced this sidewalk. Pilgrims came from across Southern California; reporters filed tongue-in-cheek dispatches.

The site seemed destined to join the roster of long-forgotten Southern California spots where believers say the Patroness of the Americas presented herself.

But the image never faded away.

That was due, in part, to the industry of members of the church. They created a small shrine and even put four traffic pylons around the spot to protect it from heedless pedestrians who just see a stain. Runoff from the rectory’s sprinklers replenishes the Guadalupe-like image every night, tracing its uncanny contours.

Votive candles are not allowed within the shrine because the melted wax “might ruin its integrity,” said Father John Cordero.

So how exactly do some people see the Virgen de Guadalupe from this humble water stain?

Its dark swirls? Those are her outer greenish-blue tunic. Lighter splotches that run down the center? Guadalupe’s pink-colored robe, her beatific face, and hands clasped in prayer. The cross-hatched edges? The rays of light that always surround Lupita.

People have shown up to pay respect, kneeling and dabbing their fingers in the murky water to anoint themselves.

The church’s two official, larger Guadalupe shrines — a statue near the confessional booths, and a fountain in the back — look lonely by comparison.

Leticia Suarez, 48, lives down the street and tends to the flowers left outside on a daily basis. She said people already attribute miracles to this Guadalupe — arthritis cured, citizenship applications granted, bills magically paid. Briseida Gomez keeps a dried rose in her office that she once grabbed from the puddle. It still gives off a fragrant scent.

“She’s telling us,” Gomez said, “not to lose faith.”

Father Cordero doesn’t call what’s in front of his rectory an apparition but a “sign” of something bigger. “We don’t know how the Spirit works, but events like this point us to a higher reality,” he said, noting that even non-Catholics walk by and linger.

People in the United States have reported cameos by the Virgin Mary on terrestrial things — on tortillas or grilled cheese sandwiches, hidden within a billboard in New Orleans, or as part of a Chicago underpass — for decades. But in recent years, as American Catholicism has increasingly turned Latino, and especially Mexican, it’s the Guadalupe manifestation of Mary that has popped up the most.

That doesn’t surprise Timothy Matovina, a Notre Dame theology professor who specializes in Latino Catholicism.

“For 500 years, she has faithfully accompanied her people in this clash and encounter of peoples called America,” he said. “Since she has been faithful to them, they are faithful to her — in fact devoted to her and seeking her accompaniment in all the joys and crises of life.”

Though it’s an area where the biggest city is named after a Virgin Mary — L.A.’s original name was El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles — Guadalupe sightings in Southern California are rare.

In 1992, an Episcopal priest led services underneath a diseased Chinese elm in North Hollywood on which he said sap had formed into her shape. That same year, hundreds claimed to have seen Guadalupe in the grime of a kitchen window in Oxnard.

Santa Ana hosted two effigies that decade: on the tile at Our Lady of the Pillar Church, and within the frosted bathroom glass of an apartment. And in 2006, workers at a Fountain Valley chocolate factory announced that drippings from a machine had hardened into the Mexican mother of God.

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles has historically frowned upon such claims by laypeople. In 2006, its then-spokesperson told The Times, “The church encourages Christians to see the face of Christ in the homeless, the poor, the destitute and the immigrant — not in a plate of pasta.”

But Ernesto Vega, the archdiocese’s coordinator for adult faith formation for the Spanish-speaking, is more understanding. In his hometown of Jiquilpán in the Mexican state of Michoacán, residents built a shrine around a boulder that they said depicts Guadalupe.

As for Holy Family’s revered water stain?

“I can see very well that it’s the shape of Our Lady,” Vega said. “But we cannot say at this moment that it’s an authentic manifestation unless there’s a movement of conversion of sinners or transformation in the community.”

He brought up the concept of pareidolia, the psychological term that describes how humans think they see patterns or images in random places. And he noted that the official Catholic Church process to verify a divine appearance is long and rarely successful; the only approved apparition of the Virgin Mary on U.S. soil happened at what’s now the National Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help in Champion, Wis., and took over 150 years for church officials to verify.

“Time is going to say if it’s authentic,” Vega said. “Some people will get tired,” but if the faith of the believers is “growing and growing and it keeps going, then that’s something else.”

The objective — or cynical — eye sees a slowly sinking sidewalk outside Holy Family’s rectory where guadalupanos insist Maria lies; they know that sidewalks are especially prone to stains and scruffs. Guadalupe? More like mineral deposits left after years, if not decades, of water evaporation that a churchgoer who was filled with religion noticed one day and declared divine.

The faithful don’t buy that explanation.

Edel Bolaños attended mañanitas Mass with his wife and a friend. “She appeared, and she hasn’t disappeared,” he said. “If it was something natural, it would’ve been long gone.”

“It’s the most marvelous thing,” said Irma Perez, whose daughter attends the church’s Our Lady of Fatima School. “This just confirms our faith.”

Lifelong Artesia resident Edward Rodriguez is hoping “we get a miracle out of this.” He said that a lot of longtime Latino residents have moved away as housing prices in Artesia have risen and wealthier immigrants have moved in. “We don’t have as much raza coming to church as before,” the 52-year-old said.

But Holy Family is “vibrant,” Father Cordero said. And what he welcomes most about his parish’s new Guadalupe is how it has “sustained us as a whole” — something that ties together the church’s different communities.

Mass is said in English, Spanish, Tagalog, Portuguese, and Chinese. Separate shrines to Our Lady of Fatima, St. Lorenzo Ruiz — revered by Filipinos — and Guadalupe dot the inside and outside of the church.

“Everyone usually sticks to their own services,” said Suarez, who’s attended Holy Family for over 30 years and had all of her children baptized there. “But out here, everyone is coming together.”

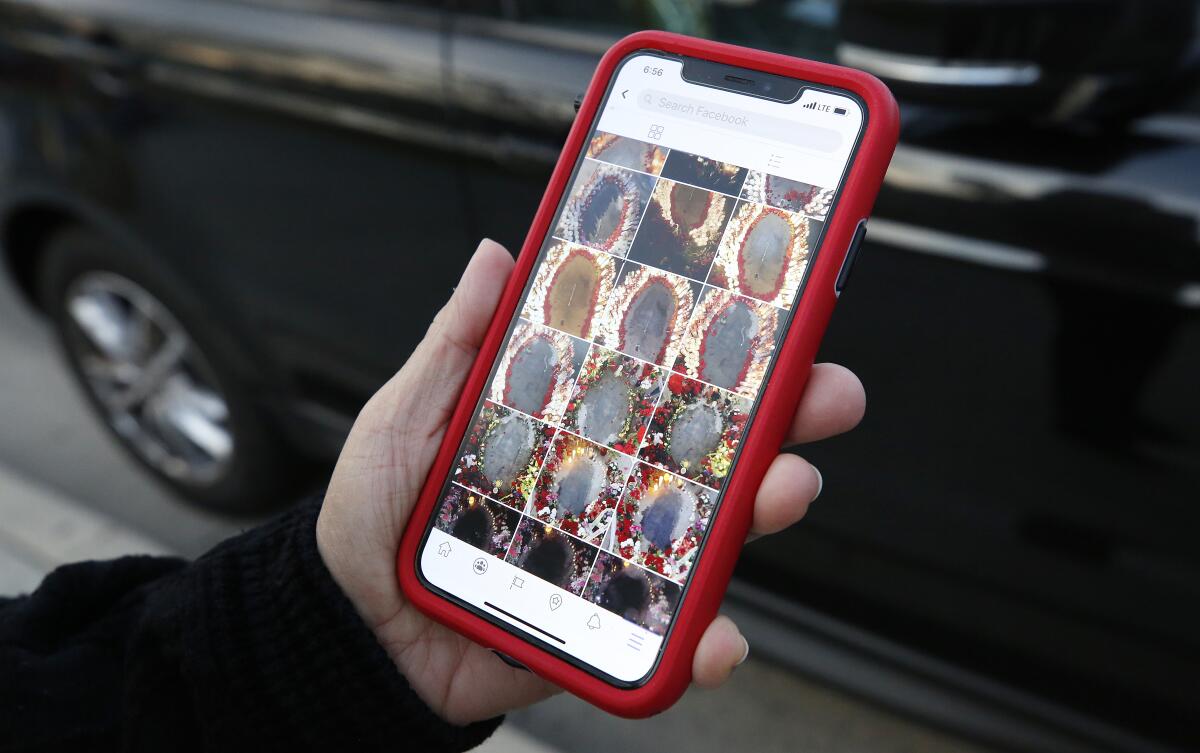

Gigi Manzanilla was one of the first parishioners for the mañanitas Mass. The Filipina immigrant has more than 500 photos of the shrine that she shares on social media, and said she has experienced her own modest miracles since last December — reconciliation with family members and a banner business year.

“All of our faith has been strengthened by her,” Manzanilla said, a silk scarf with Guadalupe wrapped around her neck. “Mama Mary is for all.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.