Officials long warned funding cuts would leave California vulnerable to pandemic. No one listened

- Share via

California public health officials have repeatedly warned over the last decade that federal budget cuts were weakening their ability to respond to a widespread health crisis like the current coronavirus pandemic.

Despite the warnings, elected leaders cut millions of dollars in federal grants and other funding to California state and county health agencies, reducing the number of medical workers, including epidemiologists, and jeopardizing the ability to do lab tests and quickly set up mobile hospitals, according to interviews and records reviewed by The Times.

The budget woes have left California desperate for more resources, including test kits and hospital beds.

A year ago, Riverside County Public Health Director Kim Saruwatari warned state lawmakers at a public hearing that the staff and budget cuts would be a serious problem in the face of an emergency such as a pandemic.

Now her fears have come to fruition.

The funding cuts, particularly to federal grants meant to bolster local preparations, have left Riverside County with “fewer trained staff to conduct case investigations and contact tracing, fewer epidemiologists to assist with analysis, fewer lab staff (public health microbiologists) and less funding for updated laboratory equipment,” Saruwatari told The Times.

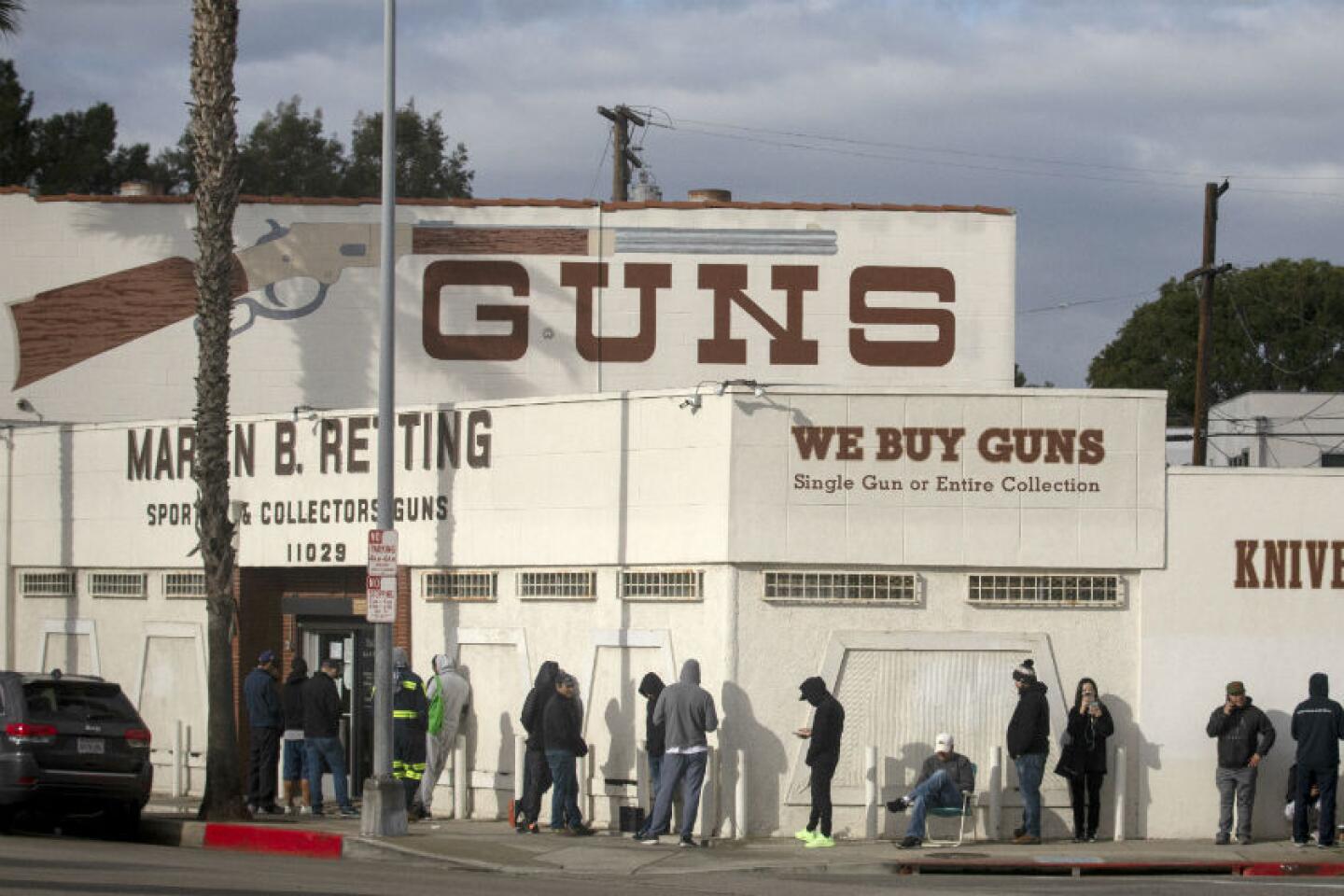

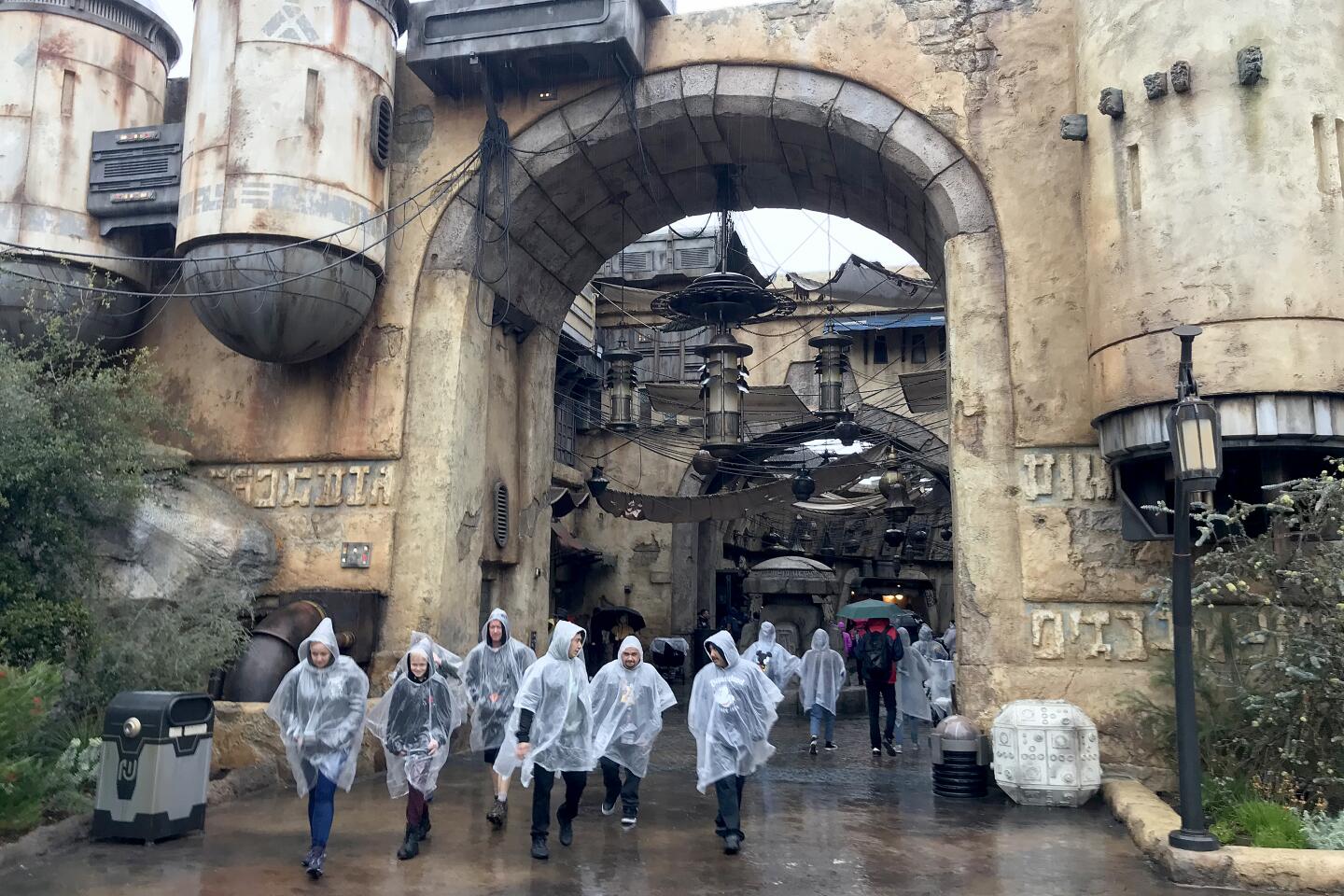

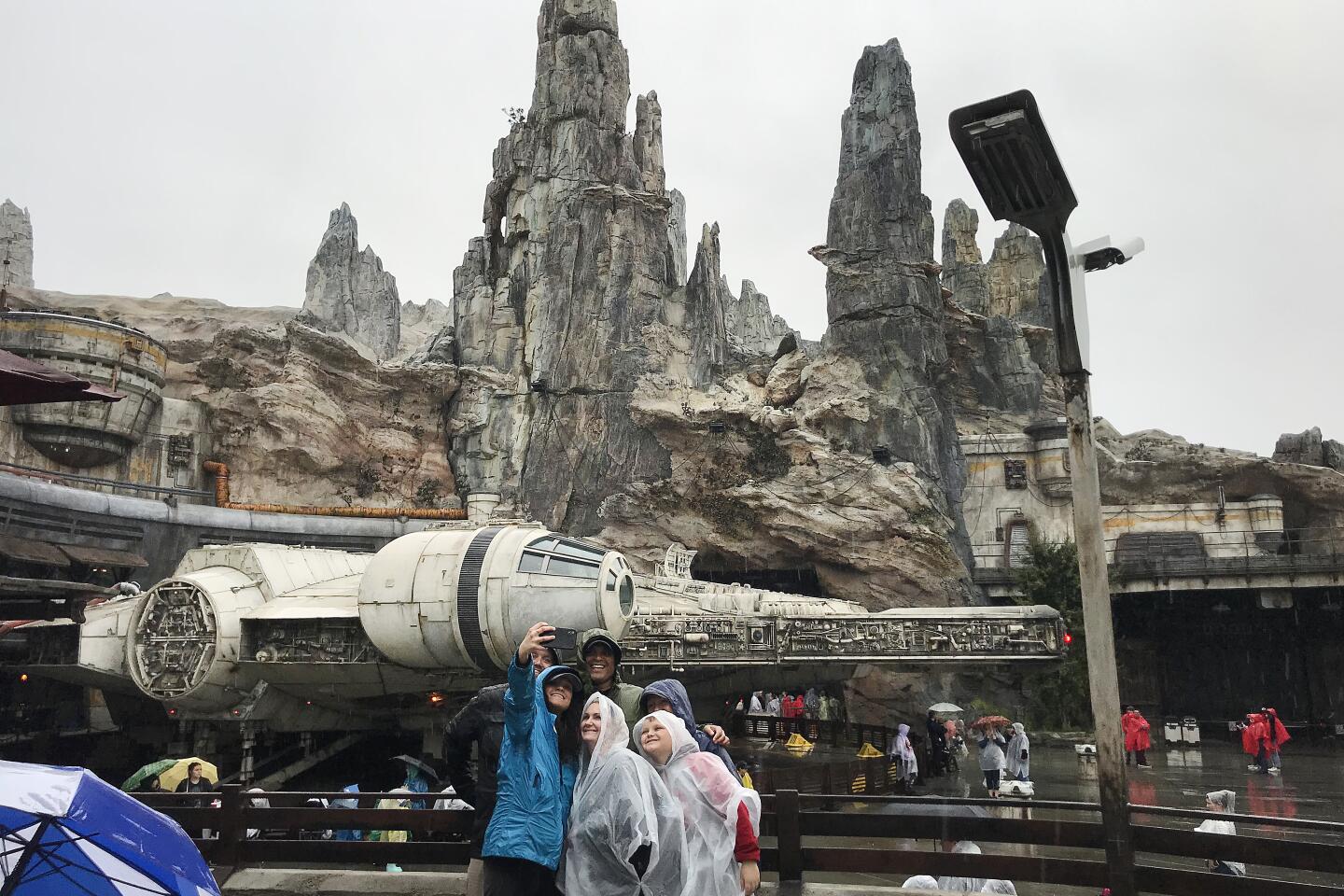

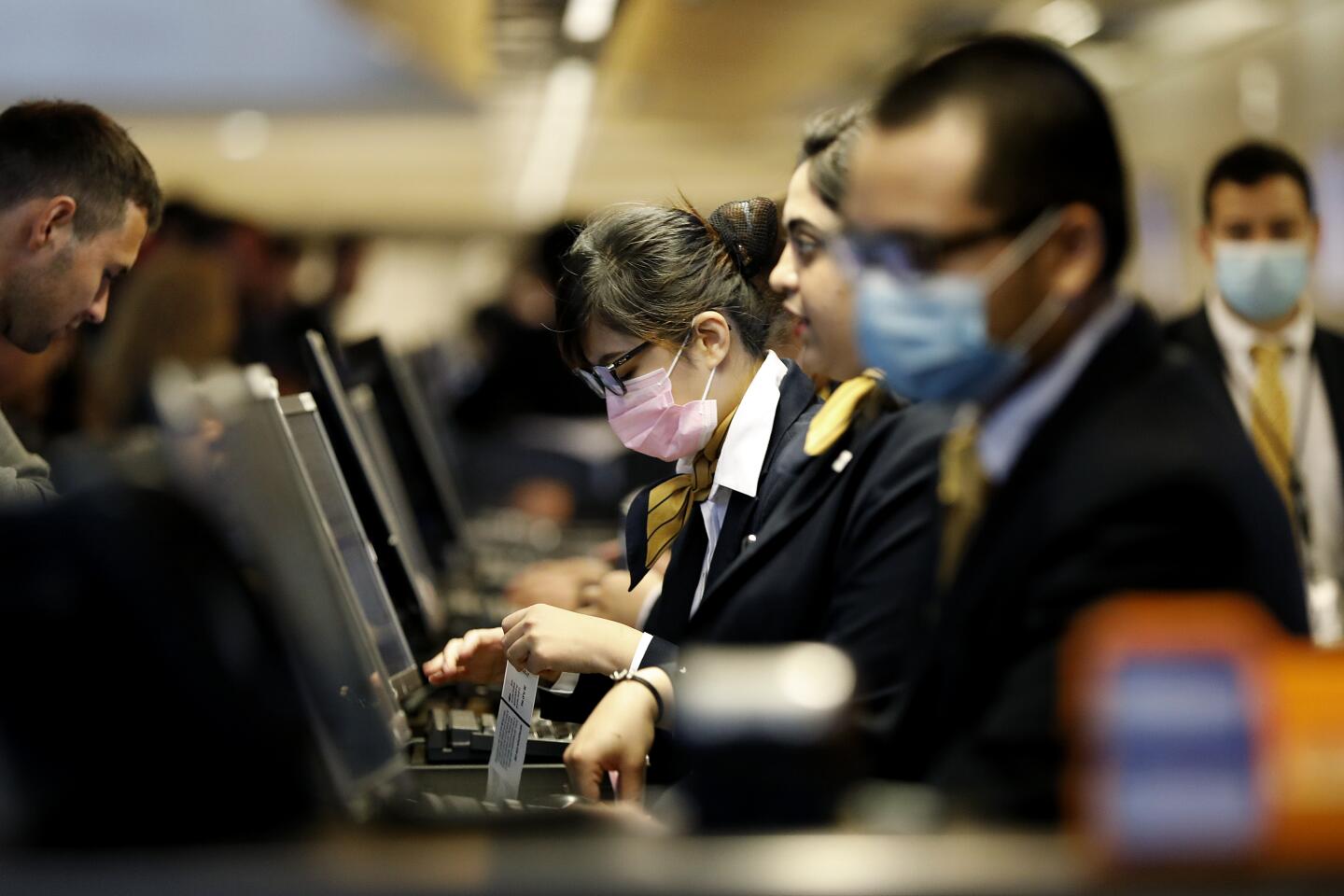

Gov. Gavin Newsom has ordered Californians to stay at home. With businesses and popular destinations closed, The Times’ Luis Sinco documented the surreal scenes.

Budget cuts also played a role in the closure of 11 local public health laboratories over the last 15 years, said Kat DeBurgh, executive director of the Health Officers Assn. of California.

Local health agencies need more staff to expand testing, operate alternative care sites for infected patients, expand call centers for the anxious public and conduct contact tracing to limit the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19, DeBurgh said.

“We can definitely see that the public health workforce has drastically shrunk and never recovered,” DeBurgh said. “That really shows at a time like today.”

Heavy cuts began during the 2007-09 recession as governments struggled with budget shortfalls. Nationwide, local public health agencies cut 55,000 jobs between 2008 and 2017, according to an estimate by the advocacy group Trust for America’s Health.

“These cuts reduced the capacity for these health departments to prevent illness and loss of life,” said John Auerbach, the organization’s president and chief executive. “Their impact is being illuminated in an all too real fashion by the novel coronavirus.”

The two main programs that fund local health preparedness are administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and its parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services. Both programs also have seen significant reductions.

In California, the annual allocations from those programs to the state and all but one of its 58 counties dropped from $81 million in 2010 to $65 million last year.

Los Angeles County health officials did not say how much funding they have received but said cuts left them short-staffed and “in some cases, activities took longer.” Still, they said they weren’t hampered as much as smaller jurisdictions around the country.

A Health and Human Services spokeswoman declined to address cuts to local health agencies but said in a statement that the Trump administration worked with Congress to boost overall funding for federal agencies involved with pandemic preparedness.

Adriane Casalotti, chief of government and public affairs for the National Assn. of County and City Health Officials, said the Trump administration in recent years recommended additional cuts but was rebuffed by Congress, though the funding remains far short of what it was a decade ago. She said local and state health departments across the country have lost nearly a quarter of their workforce since 2008.

The CDC did not respond to requests for comment.

Dr. Tom Frieden, who was director of the CDC from 2009 to 2017, said in a statement that the “U.S. has under-invested in preparedness.”

“It’s crucial that funding support not only what would be done in an emergency, but what health departments do every day to keep people safe,” said Frieden, now president and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, whose goals include making the world safer from epidemics. “Robust systems that can be scaled up in an emergency are the most effective way to reduce risk.”

His statement did not address cuts during his tenure.

A Times review of state legislative hearings shows that warnings about the consequences of the cuts were repeatedly made in Sacramento.

In 2013, the Assembly and Senate held a joint hearing called “Are We Prepared? Assessing the Status of California’s Emergency Response Capabilities.”

There, a top California Department of Public Health official told lawmakers that local health budgets had been slashed by 30% to 40% in the previous few years.

State Sen. Richard Pan (D-Sacramento), a physician who now chairs the state Senate Health Committee, recalled at the same hearing how his home county had struggled to respond in 2009 to the H1N1 flu pandemic that killed an estimated 12,500 people in the United States, according to the CDC.

He said Sacramento County public health officials told him at the time that many of the health workers who deployed to combat the flu crisis did so shortly after they were given pink slips notifying them that they would soon lose their jobs.

State Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson (D-Santa Barbara) was particularly upset to hear in 2013 that state budget cuts could delay setting up of some of the state’s mobile hospitals in the event of an emergency.

“This to me is a violation of our responsibilities as a government to the people,” Jackson told health officials at the hearing.

Last year, Dr. Karen Smith, then California’s public health officer, told lawmakers she remained concerned about the years-long reduction in the number of public health nurses, epidemiologists and communicable disease investigators working for public health agencies in California.

“It’s this very infrastructure of trained, skilled people that has been significantly eroded over the past decade,” Smith told the Senate Health Committee. “The loss of our experienced public health workforce at the local level actually represents a very real threat to the health of California.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom responded to concerns by allocating $40 million last year to assist county public health agencies in fighting infectious disease, which local officials said was a good start.

But the consequences of more than a decade in cuts have become even clearer in recent weeks.

In 2011, the state eliminated the $1.7-million budget for its Mobile Field Hospital Program. Two mobile shelters have been kept in storage, and a third was divided and parceled out to local emergency agencies.

The state could still deploy its mobile structures to assist with the COVID-19 pandemic, but officials said they have not yet decided whether to do so.

Pan acknowledged again last week that preparedness in California has suffered.

“Unfortunately, while the Congress has tried to sustain funding to agencies like the CDC, they have also cut back on funds that get allocated to state and local health departments, and we need to change that,” Pan said during a legislative hearing March 12.

In the scramble to make up for lost time, state officials this week approved an emergency infusion of $1 billion in state funds for various programs to fight the coronavirus outbreak. Federal officials are also dipping into their treasury to get money to the states.

“We are reassured that resources are not the issue here,” state Public Health Officer Dr. Sonia Angell said last week.

On Thursday, Newsom told congressional leaders in a letter that $1 billion is needed from Washington to help California and its counties deploy mobile hospitals and procure more protective equipment, ventilators, tents, cots and sheltering supplies.

But some public health officials say money was needed sooner to react promptly to the crisis.

Dr. Jonathan Fielding, who led the L.A. County Department of Public Health from 1998 to 2014, said there was a significant nationwide reduction in staff and resources at health departments during his tenure.

That’s making it harder for authorities to respond to the coronavirus outbreak, said Fielding, now a professor at the School of Public Health at UCLA.

The biggest obstacle U.S. health officials face is the lack of tests for COVID-19, he said. But another, less obvious way the manpower shortage could be hampering the response is in tracking the origins of new cases.

“That was one of the first things we needed to do, and it can make a huge difference,” Fielding said. “It’s very disappointing how slow we were in the United States.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.