- Share via

The videos are horrifying. In one, a black dog hangs by its neck, crying and convulsing as it is blowtorched alive. In another, a white dog dangles from a wooden beam, writhing in pain and terror.

The footage came from a 2016 trip to Asia by Marc Ching, a Los Angeles resident who spent nearly a decade in prison for a violent crime before transforming himself into a prominent leader in the local, national and international animal rights communities.

Ching has told supporters that those videos and others were recorded to document the torture and slaughter of dogs at meat markets in Indonesia, Cambodia and other countries in Asia with a limited but enduring trade in butchering the animals for human food.

The gruesome images appear on social media and in an emotional public service announcement that features a roster of celebrities, including Matt Damon, Joaquin Phoenix and Rooney Mara, and promotes a charitable foundation that Ching started. The Animal Hope & Wellness Foundation has raised millions of dollars for the purpose of rescuing dogs and cats from Asian slaughterhouses.

“It shows you why this has to end,” Ching said after screening the videos at a House briefing in 2016 on Capitol Hill. As he showed the torture scenes, audience members gasped and averted their eyes. “How can you do that to an animal?” Ching asked.

But a Times investigation has found evidence that contradicts Ching’s claims about the authenticity of some of the most shocking videos and raises questions about his rescue efforts overseas.

Butchers in Indonesia have told The Times that Ching paid them to hang the black dog and burn it to death — a method of killing more cruel than any they say they normally employ — so he could stage the scene for the camera.

In appeals to the public and foundation supporters, Ching has presented videos of that incident and others as candid portrayals of the day-to-day routine at the slaughterhouses he documented mostly while “undercover,” posing as a dog meat buyer. But local animal rights activists in Indonesia, Cambodia and elsewhere in Asia say they have never heard of dogs being regularly tortured or killed in some of the ways depicted by Ching.

And raw footage of Ching’s recordings obtained by The Times casts doubt on whether all of the videos show how butchers typically torture and kill the dogs.

One of the unedited clips captures the dog being burned alive. In a sworn court declaration filed in August 2017, Ching wrote that he happened to be investigating the dog meat trade at a market in Tomohon, Indonesia, when he and his interpreter “stumbled upon” the burning.

Ching wrote that it “was taking place in broad daylight while passersby ignored the dog’s screams. My translator filmed the gruesome act only to use as evidence of the cruelty happening in Indonesia.”

But nearly seven minutes of the raw footage shows the dog being pulled from a cage with a noose and carried through the market by a butcher while Ching’s camera follows him from behind. The camera continues to roll as the animal is strung up by its neck and slowly torched to death. As the dog burns, the butcher looks toward the camera and gives a thumbs up.

Ching, 41, denied orchestrating that scene or any other and said he never instructed butchers on how to maim or kill dogs.

“If the question is if I pay people to torture dogs — no, I don’t,” Ching said.

In an interview and a subsequent email to The Times, Ching said the allegations against him were motivated in part by rivalries among animal rescuers. Ching accused two activists of conspiring to bribe a butcher in Indonesia to say Ching paid to stage the burning of living dogs.

“Groups slander each other constantly based on the fact that they believe or feel they know better,” he said in the email.

“If the question is if I pay people to torture dogs — no, I don’t.”

— Marc Ching

The animal rights activists deny bribing any butchers, and The Times found no evidence of a conspiracy to falsely accuse Ching of wrongdoing.

::

Ching’s foundation held a gala fundraiser in 2017 at the W Hotel in Hollywood, drawing the likes of No Doubt bassist Tony Kanal, who told an interviewer at the event that Ching was a “superhero.” Others in attendance referred to him as an “Earth angel.”

A whistleblower and watchdogs raise concerns over cash withdrawals, allegedly deceptive solicitations and other financial practices at the Animal Hope & Wellness Foundation. The charity denies misleading donors or misusing money.

In March 2019, musician Moby and actresses Alicia Silverstone and Shannen Doherty attended a Culver City fundraiser for the foundation that was hosted by comedian Whitney Cummings. Doherty, who once sat on his charity board, told an interviewer at the event that Ching had “the greatest spirit and always the best of intentions.”

As the star power elevated Ching’s profile, the foundation helped secure a federal law that effectively banned the human consumption of dog and cat meat and a California prohibition on new fur products. Donations continued to roll in.

The Times’ investigation also found that Ching’s charity has engaged in financial practices that nonprofit experts say are troubling. Foundation records show that more than $350,000 in cash was withdrawn from the charity in a period of 27 months and that Ching has billed the foundation for at least $59,000 in food and other products from his for-profit pet nutrition business, the Petstaurant.

In emails to The Times, and through statements by the foundation’s attorneys, the organization said Ching never misused funds and had contributed hundreds of thousands of dollars in goods, services and cash to the charity since 2014.

Last month, the Federal Trade Commission accused Ching of making false or deceptive claims that an herbal supplement he was selling could treat COVID-19 and that some of his other products could treat cancer. Ching denied wrongdoing and said he was cooperating with the commission.

Marc Ching, a prominent Southern California animal rights advocate, has agreed to stop pitching an herbal supplement as a remedy for COVID-19.

Board members who oversee Ching’s foundation initially declined to meet with The Times, and the organization at one point suggested the newspaper had tried to persuade people to lie about Ching and the charity.

Dr. Barbara Gitlitz, a Los Angeles oncologist who chaired the charity’s board at the time, eventually sat for an interview in January in the Wilshire Boulevard offices of the foundation’s attorneys. She said she had no reason to doubt Ching’s accounts of the dog torture and that she questioned the credibility of the butchers who accused him of paying them to stage abuse.

“It just goes against everything that I know about Marc and how he treats animals,” Gitlitz said.

Two days later, she emailed The Times to say the board was launching an independent investigation. She and a foundation attorney did not respond to follow-up questions about the investigation, including a query on who conducted it. The foundation also did not respond to questions of whether any recent changes had been made in the board membership, including the chair position.

In a recent email, the attorney, Russell M. Selmont, said the charity had found no evidence that Ching “ever staged the burning of any dogs (at Tomohon market or otherwise) or ever knowingly or intentionally contributed to the harm of any animals.”

He called the butchers’ accounts unreliable and said Ching’s videos threatened “to expose their inhumanity and shut down their livelihoods. The notion that Mr. Ching paid these butchers to burn and torture the dogs is sick, twisted fantasy.”

::

Ching has publicly drawn on his time in prison to explain his devotion to the plight of caged animals. At a 2017 animal rights march in Los Angeles, he delivered a tearful speech, telling demonstrators that during a long stretch in solitary confinement, a scout ant crawled into his cell and took a nibble of a little ball of bread he had saved to lure the insect. The ant left, he said, but in about an hour and a half thousands of them were in his cell.

“It was the first time in so long that I had the contact of anybody or anything,” he told the crowd, his voice catching.

But Ching, who was born in Hawaii and attended the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, has revealed little about what landed him behind bars.

In what authorities called a “heinous” and “sophisticated” crime, Ching and several accomplices abducted a man who had stolen $60,000 in a drug deal, bound his hands and drove him to a hotel, where they removed his pants and beat him at length, court records show.

Corrections officials said he served nine years and seven months in prison for kidnapping and causing great bodily injury. Valarie Ianniello, former executive director of the foundation, said Ching told her he spent 11 months in solitary confinement. A California prisons spokeswoman said there was no record he was ever placed in any type of solitary housing.

Ching did not dispute the lack of such a record, but he said in an email to The Times: “My experience is my experience. And because your definition of confinement differs from mine, that does not make my experience not true.”

Two years after his release in 2010, Ching registered his pet food business and the Animal Hope & Wellness Foundation with the state. He describes himself as a fourth-generation herbalist and nutritionist. He also opened the Petstaurant store on Van Nuys Boulevard in Sherman Oaks. In 2015, Ching began making regular trips to Asia and posting disturbing images on social media.

“In Asia once I watched them crucify dogs…. They would get their paws and they would nail gun them into walls.”

— Marc Ching, in a BuzzFeed interview

He soon became something of a media darling, telling harrowing tales of being assaulted, threatened with a machete, shot at and nearly killed while uncovering animal abuse overseas.

“In Asia once I watched them crucify dogs,” he said on camera in a 2016 BuzzFeed interview, his eyes red and wet with tears. “They would get their paws and they would nail gun them into walls.” (Ching did not respond to requests from The Times for any documentation or further details of this incident and the more serious of the alleged assaults against him.)

He added: “I have videos of hangings, burning them alive, boiling alive, cutting their feet off while they’re still alive, strangulation.”

The segment has been viewed more than 3.9 million times. Viewers praised him online as a hero. Contributions to his foundation surged — from about $110,000 in 2015 to nearly $2 million the next year, according to the charity’s tax records.

“I think he recognized that he could be worshiped by this stuff,” Ianniello said. “The money came in, and it helped build his business up.”

Ching has opened a second Petstaurant on the Westside.

::

There is no dispute that dogs and cats are killed for food in countries across Asia, especially outside the major cities. Local activists in those countries have long fought to end the practice, often working in league with Westerners.

Foreign and U.S. activists interviewed by The Times said the methods used by butchers to round up and kill the animals — packing them into cages, drowning them, clubbing them on the head and, in some cases, hanging them — are uniformly inhumane.

They said there had been instances when animal abusers burned dogs alive or brutalized them in other ways, and images of the cruelty are posted online. And there have been many times when butchers, after striking a dog’s skull to kill it, burn the animal to de-fur it, even though it is still alive.

But all of the activists, including seven who do work in Asia, said their efforts had found no evidence to support the notion that the dogs are routinely and deliberately burned or boiled alive, or tortured with beatings and mutilations on a regular basis as Ching has described.

“We’ve never seen animals boiled alive, never seen animals beaten or paws cut or anything,” said Lee Fox-Smith, an author who co-founded the Campaign to End the Dog Meat Trade in Cambodia. Since 2017, Fox-Smith said, he has visited more than 200 slaughterhouses and restaurants that serve dog meat.

He said he initially was afraid to investigate the meat trade because he had heard Ching’s tales of danger. But when he started visiting slaughterhouses, he said, he found that they were the “complete opposite” of Ching’s portrayals.

“People aren’t chasing you with machetes and guns,” Fox-Smith said.

He said he first contacted Ching through Facebook in 2018 and offered to help Ching’s foundation shelter dogs rescued in Cambodia. They met twice in that country, Fox-Smith said, and he questioned Ching during the second meeting about Ching’s claim that dogs were boiled alive in Cambodia.

Fox-Smith said Ching told him, “They don’t really torture the dogs in Cambodia.”

“He’s basically taking the most vulnerable animals in our society and exploiting them … and it’s disgusting,” Fox-Smith said.

He said Ching was cagey in answering other questions and declined to disclose the locations of slaughterhouses he had visited, making it impossible for Fox-Smith to verify Ching’s claims.

At the market in Tomohon, Indonesia, butchers gave The Times a much different account of the dog torched than Ching offered in his court declaration. They said Ching specifically wanted the dog burned alive, something they and others insisted was not normally done at the market.

In the raw footage The Times obtained, a man is seen pulling the dog from a cage by its neck. Marthen Wondang, a butcher, moments later takes the dog, hanging from a noose, through the market.

Someone yells out about a demonstration as Wondang carries the dog to a patch of dirt where chickens are underfoot.

As the dog tries to escape, Wondang twice throws a rock at its head, subduing it before hanging the animal from a wooden cane. Another butcher starts to blowtorch the dog, which thrashes about in agony. Wondang looks toward the camera and flashes a thumbs up. In a language local to the area, he asks a question whose English translation is, “This is exactly what you want, right?”

A minute and 19 seconds into the burning, the dog, its body charred, lets out its final whimper.

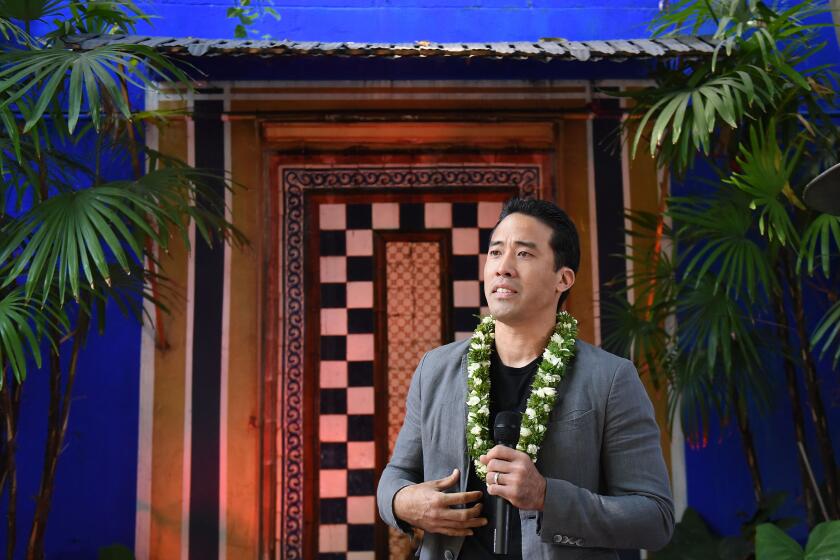

Butchers in Indonesia told The Times that animal rights activist Marc Ching paid them to hang and burn a dog alive — a method of killing more cruel than any they say they normally employ — so he could stage the scene for the camera. Ching denied doing so, and his foundation questioned the butchers’ credibility, saying his work threatened their livelihoods.

The market has earned a grisly reputation thanks to social media and animal welfare campaigns.

In one section under brightly colored tarpaulins, vendors hawk local favorites such as smoked skipjack tuna, spiky golden pineapples and tropical jeruk manis oranges that turn green when ripened.

The center of the bazaar features rats impaled on bamboo sticks, listless reticulated pythons coiled into mounds and charred bats, mouths agape and showing off rows of fangs and thick, pointy tongues. The smell is a noxious mix of cigarette smoke, unrefrigerated meat and kerosene from blowtorches singeing away dead animal hair.

Dogs are kept in small cages on wheels before they’re slaughtered, their tails tucked between their hind legs and faces withdrawn with droopy eyes.

Despite opposition to the dog meat trade, local governments often don’t enforce laws in some rural areas of Indonesia where consuming dogs endures, activists say.

Several butchers in Ching’s videos told a Times reporter on a recent visit to the market that they met Ching when he showed up with an interpreter in 2016, saying he wanted to buy dog meat. Wondang said Ching bought four dogs at an inflated price and asked that they be killed in particular ways, including torching one alive, while he recorded video.

Ching “was smiling and laughing throughout the process … like he was happy.”

— Marthen Wondang, butcher

Wondang and the other butchers said they typically killed dogs by beating them on the head. Burning dogs to death, they said, would be too costly in terms of kerosene and more likely to result in the butchers getting bitten or scratched.

Strangely, Wondang said, Ching left the dog meat behind after he finished recording.

“He was smiling and laughing throughout the process,” he said of Ching. “Like he was happy.”

Ching did not respond to a question about that claim. He said one of the butchers, whom he did not identify, told him in 2016 that they burned 50 dogs to death a day at the market.

In interviews with The Times, animal welfare activists based in Europe and Asia said some of the butchers had given them the same account of Ching paying to have the dog burned alive on camera. They said the butchers told them this separately at various times between late 2017 and spring 2018, well before The Times began its investigation.

Lola Webber, Bali-based co-founder and director of the Change for Animals Foundation, a charity registered in England, told The Times she visited the Tomohon market around Christmas 2017. She said “maybe three” butchers, including one she recognized from Ching’s videos, together approached her group asking whether they were with Ching. Webber said she told them no.

The butchers related that Ching had paid them to torture the dogs on camera in certain ways — one hanged, another torched alive, Webber said.

She said she had a similar experience when she visited a meat market in nearby Langowan. About five butchers walked up to her group and asked whether they were associated with Ching, she said.

“We said, ‘No, we have nothing to do with Marc Ching,’” Webber added. “They said, ‘Do you want to pay us?’”

Webber said Ching’s actions undermined the work of activists devoted to ending the dog meat trade, which kills dogs in ways that are cruel enough. “It’s totally shameful,” she said.

Frank Manus manages Animal Friends Manado Indonesia, which operates a shelter in Tomohon. He said that during a brief meeting in 2016, Ching showed him photos of a dog being burned alive at the Tomohon market. Manus said he immediately doubted the photos.

“I go to the market every day, and no such thing happens,” Manus said.

Other activists have questioned Ching’s videos. He sued one of them: Deborah Hall, a volunteer who posted on Facebook that Ching “paid to have dogs torched and legs cut off,” according to the suit. A judge tossed the part of the lawsuit concerning that statement. Hall declined to comment on the suit, which the parties eventually settled.

Sebastian Margenfeld, a German activist, said he first learned of Ching in 2016 when he stumbled upon a YouTube video on Ching’s rescues in Asia. He said it moved him so much that he reached out to Ching’s charity with the goal of producing a public service announcement, or PSA, in German similar to the foundation’s, using the same footage.

Soon after, Margenfeld said, he started his own foundation with a name that echoes that of Ching’s charity when translated into English. Margenfeld said the early web postings of his foundation focused on Ching’s work. He added that his foundation later contributed more than $50,000 in funds and services to Ching’s efforts, including the cost of flying American veterinarians to China.

In the meantime, he said, Ching’s foundation put him in touch with the production company that created its PSA, Sugar Studios LA, which sent Margenfeld a zip file in November 2016 with Ching’s raw footage.

Margenfeld said he watched it all. He offered to join Ching on rescue missions, but Ching always refused the help.

It wasn’t until he visited Indonesian slaughterhouses in April 2018 to shoot his own footage that he began to question Ching’s footage, Margenfeld said.

“Because I had never been to Asian slaughterhouses, I thought it was real,” he said of the torture. “I went to Tomohon and it was so different from Ching’s video.”

Margenfeld, who is a physical therapist in the town of Freiburg in southwest Germany, said he told the foundation board members of his suspicions about Ching in a May 2018 conference call. The board members stood by Ching, Margenfeld said.

In 2016, Ching traveled to Cambodia with a professional cameraman to film more slaughterhouses. Raw footage from the trip features long monologues during bumpy car rides in which Ching chokes up as he reflects on what he says he witnessed.

“The people that really hurt these animals, they’re going to hurt children,” he says during one ride. “They’re going to molest kids, kidnap people, they’re gonna beat them up.”

In one scene, Ching is kneeling beside a brick cage of dogs describing the meat trade for the camera.

“How many dogs you want?” his interpreter is heard asking him shortly after.

Ching cuts him off by saying “whoa” several times and “time out,” while making a gesture to direct the cameraman to stop shooting. The cameraman points the camera down but keeps it rolling.

Dressed in a black T-shirt lettered #CompassionProject with the foundation’s web address, Ching says to the cameraman, “You know going undercover, they show us, just because as a dog meat buyer, usually, this guy is gonna tie one up, he’s gonna hang one over here, and beat him.

“You know, we’re gonna cut him down so he doesn’t kill the dog and stuff,” he continues on the footage. “So are you OK documenting that stuff?”

Someone says, “Yeah.” And Ching replies, “I’ll just do one then.”

After a few moments, the cameraman asks, “Do you feel like this is necessary?”

“It’s up to you,” Ching replied. “I’d rather not document it…. When I go undercover, I don’t know, I like it better, because, like, it’s just natural, you know. They’re doing it already.”

A person familiar with the incident said Ching had arranged to have the slaughterhouse hang and beat the dog for the purpose of filming it. The person, who asked not to be named for fear of retaliation by Ching, said the hanging and beating ultimately did not occur.

A person familiar with the incident captured on this video clip said Ching had arranged to have the Cambodian slaughterhouse hang and beat the dog for the purpose of filming it. The person said the hanging and beating ultimately did not occur. Ching denied making any arrangement to harm a dog. An attorney for his foundation described the clip as a discussion about filming a “dramatic reenactment” of a previous hanging at the slaughterhouse, without harming the dog.

Ching and two Los Angeles attorneys for his foundation offered a series of descriptions of the clip.

Jeremy Gray, one of the lawyers, said in an email to The Times that the video from Cambodia “appears to be a misleadingly doctored clip that is removed from its appropriate context.”

The Times engaged an audio-visual forensics expert in Michigan, Ed Primeau, to analyze the Cambodia footage. Primeau said he found no evidence that it had been altered.

“These video recordings are authentic and represent the events as they occurred,” he said.

Ching later said in an email to The Times, “It is likely that the clip recorded a discussion about organizing the filming and that may have included some payment to enter the slaughterhouse.” He said that there was no plan to mistreat a dog and that no animal was hurt.

Selmont, the other attorney for the foundation, described the clip as a discussion about filming a “dramatic reenactment” of a previous hanging at the slaughterhouse without harming the dog.

“Mr. Ching and the foundation ultimately decided against including anything like that in the documentary and the videographer himself has confirmed that no such event ever occurred,” Selmont said in an email.

Selmont said the earlier hanging occurred several months before the discussion on the clip: “Mr. Ching posted an iPhone video of him cutting down a dog that he saw in real time being hung at a dog butcher. Mr. Ching, at that exact moment, paid for the dog and filmed himself in real time cutting down that dog who otherwise [would] have been slaughtered for meat.”

The foundation’s PSA includes a shot of Ching cutting a hanging dog free.

In another clip from Cambodia, a young man in board shorts drops a live dog into a vat of scalding water. As the dog thrashes about, the man quickly jumps back to avoid getting splashed. Moments later, the vat falls over as the dog tries to escape.

Activists told The Times that dogs are not normally boiled alive in Cambodia, if only because the butchers could be scalded in the attempt. They said those vats were often used instead to de-fur dead dogs in boiling water. In the background of the Cambodia clip, a second young worker is seen removing the fur from what appears to be a dead dog in a similar tub of steaming water.

On numerous occasions, Ching claimed that his life was in danger in Asia. When first asked for details by The Times, Ching responded with written descriptions of two car crashes, getting into altercations in Cambodia and China, being punched in the face in Korea, various encounters with butchers who threatened but did not injure him, and being pushed off a “small cliff” in Taiji, Japan.

The Times then presented Ching with information from media interviews and social media posts in which he is quoted as saying that, in addition to several assaults, he was shot at, had a machine gun stuck in his mouth and almost died four times. Ching responded that he had tried to suppress his memories of those incidents — which he has said occurred in recent years — because of their traumatic nature.

“Those things happened to me,” Ching said in an email. “Over the years both intentionally and I believe subconsciously I have tried to forget the worst of these experiences as it is best for my mental health.”

Ianniello, the foundation’s former executive director, said Ching told her of an incident in which he was pushed to the ground at a slaughterhouse, where he swallowed feces and blood. Ching said that as a result he contracted flesh-eating bacteria that required surgery to eliminate, according to Ianniello and another former foundation employee, Kiana Kang.

Ching did not respond to a Times query about the incident. He would not provide The Times with any documentation or other means of verifying the more serious episodes, such as medical records or the names of any witnesses. His foundation said in an email that Ching never reported the assaults to Asian authorities or to American diplomatic officials because doing so “would have affected the mission of the trips.”

Pringle and Tchekmedyian reported from Los Angeles, and Pierson reported from Indonesia. Alice Su and Gaochao Zhang of The Times’ Beijing bureau and special correspondent San Sel in Cambodia contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.