Young Black activists are inspired by past generations. But they’ve moved beyond ‘respectability tactics’

- Share via

Pastor Eddie Anderson was sensing a generational split among his fellow Black activists, and it frustrated him.

The minister had gathered with other church and community leaders on a recent weekday in a South L.A. church. He listened as the elders discussed with the chief of police and sheriff how to move forward after several days of protests across Los Angeles.

As the youngest person in the room, the 30-year-old appreciated the perspective shared by those decades older. But he felt that a discussion with law enforcement wasn’t the best way to meet the moment. A key voice was missing at that meeting, he said.

“There were not young people in the room, and not young people given the mic to speak, and so we keep perpetuating the same systems,” he said.

For the last two weeks, Black demonstrators, many in their teens, 20s and early 30s, have given voice to an ambitious new agenda for social change that goes beyond the demands of some previous generations of activists, Anderson suggested.

“People are telling you what they want. They want to defund police. They want to prosecute killer cops,” said Anderson, who hosts Black Lives Matter meetings at McCarty Memorial Christian Church.

It’s not a matter of disrespecting elders, Anderson said — more a question of whether it was the right call to gather with the heads of institutions that are mistrusted and under scrutiny.

“This is a Third Reconstruction moment,” he said, alluding to two previous periods in which African Americans strove to combat white supremacy: the decade after the Civil War and the civil rights era of the 1950s and ’60s. “So let’s lean into the moment and not be so stuck to tradition that we stagnate the movement.”

As demonstrations have erupted across the country in response to George Floyd’s killing in police custody May 25, many Black Americans have reacted in ways that reflect overlapping, yet distinctive, generational experiences and perspectives.

Black activism is not monolithic. But some differences among age groups, activists and community leaders say, have centered on younger protesters rejecting “respectability politics” — the idea that Black Americans should wear their Sunday best and adopt an attitude more mollifying than militant in order to gain equal rights — and challenging the belief that simply sitting at the table with those in power will effect change.

During the early years of the civil rights era, particularly in the Jim Crow South, Black demonstrators were instructed by their pastoral leadership to stick religiously to a script of nonviolent resistance, partly so as not to provoke additional brutalities from police and hostile whites. Rank-and-file members sometimes were even instructed what to wear at demonstrations. Actions were tightly disciplined, leadership was centralized, and organizational strategy flowed from the top down.

Those methods eventually helped secure passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Many of today’s young Black activists say such tactics no longer work, particularly in dealing with unrelenting police brutality. They are not afraid to interrupt Police Commission meetings or show up on the doorstep of Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey. Black Lives Matter organizers and other young activists have called for defunding the police, a People’s Budget, prosecuting police and, more broadly, ending what they call state-sanctioned violence.

“The previous generation of community organizers that were responsible for successful policy changes used respectability as a strategy to disrupt the archetype of what a Black person would look like,” said Tyree Boyd-Pates, 31, a public historian and museum curator based in Los Angeles. “This generation is not using tactics of respectability.”

The current movement for Black lives, scholars assert, is more intersectional than any of its predecessors and includes more women in leadership roles, as well as members of the LGBTQ community. Black queer women, in particular, deserve the credit for the Black Lives Matter movement, Boyd-Pates said. Leadership is decentralized, rather than focused on a single charismatic figure.

Those generational differences reflect the different moments in which the activists were raised and came of age politically, said the Rev. Cornell William Brooks, professor of the practice of public leadership and social justice at Harvard University and former president of the NAACP.

“The young activists of the ’60s were the infants and the toddlers of Brown vs. Board of Education, so they came into activism in the wake of a landmark legal decision, which validated the proposition that if you come to the table, you can bring about an affirmation of your humanity,” he said. “If you came of age in the wake of Trayvon Martin, if you came of age in the midst of the term of the nation’s first African American president, when there is rampant police brutality, there is a collective sense of frustration.”

Some tactics have evolved naturally: Whereas Black civil rights activists a half-century ago relied on pamphlets and phone trees, and had their actions publicized and framed largely through white-controlled media and a limited number of Black outlets, organizers today quickly spread their message through social media. Videos of police brutality are posted with ease for all the world to see.

Other tactical changes mirror long-term societal shifts. Black Lives Matter is intentionally inclusive, expanding its focus to make room for LGBTQ members and female leaders, said Andra Gillespie, a scholar at Emory University whose research focuses on the political leadership of the post-civil rights generation.

“It in part rejects respectability politics because respectability won’t save you,” she said. “And if justice is truly just, it’s true for everybody. That’s the part that is different.”

That shift toward inclusiveness marks one of the most important differences between the movements of the past and present, said Shamell Bell, a professor of African American studies at Dartmouth College.

Historically, social protest has reached a boiling point when Black men are brutalized and killed, but activists today are taking a more intersectional approach that pays equal attention to violence against women and the LGBTQ community, said Bell, an original member of Black Lives Matter who protested in 2014 in front of the L.A. Police Department headquarters over the fatal police shooting of Ezell Ford.

Today’s activists also are moving away from “the talk,” she added, referring to the cumbersome conversation that many Black parents have with their children — especially boys — about how to interact deferentially with police to avoid being harmed.

“We are telling our children these are the things happening in our society because of the color of your skin, because of white supremacy. We explain in these terms,” she said. “Something Black Lives Matter has been saying for a long time is that all Black lives matter. That is where I see us moving.”

Like many of his peers, Boyd-Pates, the museum curator, practices a form of activism that thrives online and focuses on digital community organizing. Earlier this month, he distributed an anti-racist tool kit called “Freedom Papers,” which he sent to his social media network and their allies so they could better understand Black political education.

“Intergenerationally speaking, this generation has a set of tools in its tool kit — technology that wasn’t available to the previous,” he said. “The approach to challenging white supremacy is something that my generation is actively reimagining, envisioning what it could look like beyond the politics of respectability in order to be deemed more human.”

To some older activists, their younger counterparts simply lack a plan for the future.

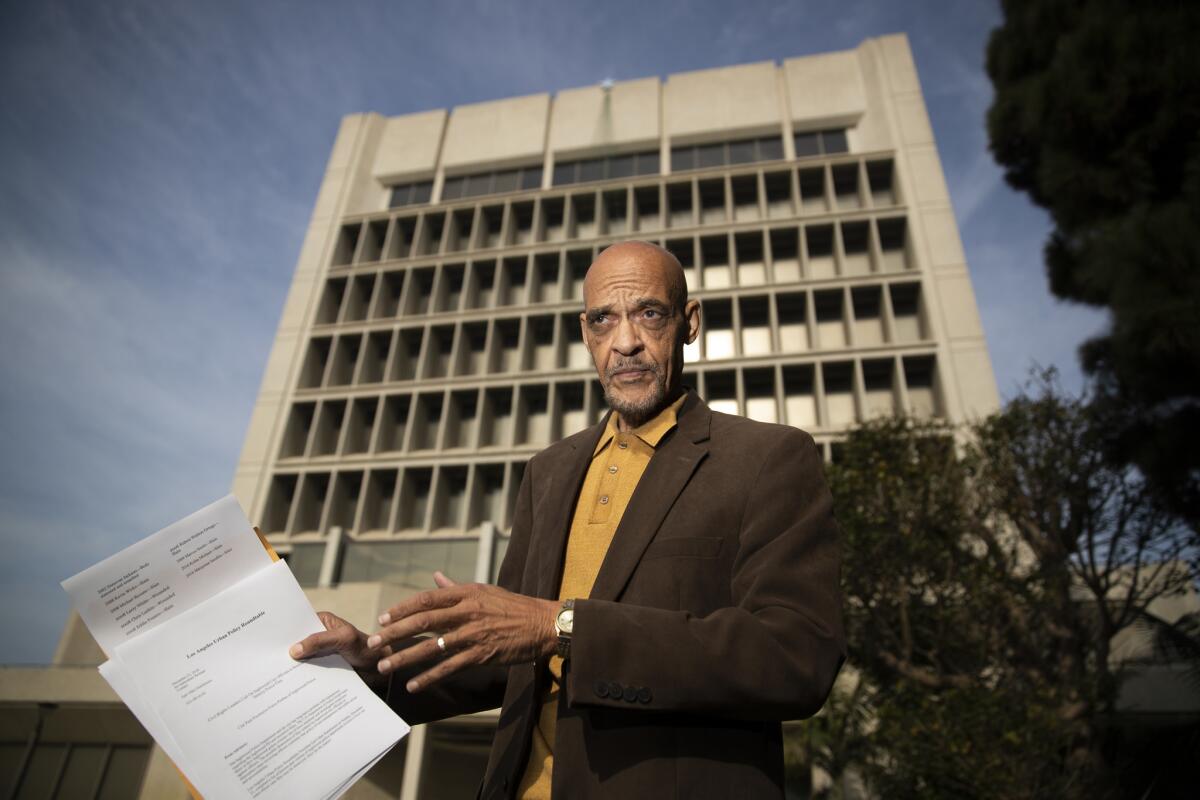

“We support the demonstrations and protests — it’s not a put-down,” said longtime community activist Earl Ofari Hutchinson, president of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable. “But history has shown protests are going to end, people are going to run out of steam — and then what?”

His critique, he said, is not of young protesters’ demands but a question of how they will follow through on them.

“You had about 100,000 people in Hollywood, but did you have voter registration tables there?” said Hutchinson, 72. “These are young people; they don’t vote, as we know. Was there a list of things for people to do? Interacting, writing letters — were these things thought of?”

The structures and institutions may not work the way other activists would like, he added, “but it’s all we have.”

“It’s like saying I’m not going to vote because it doesn’t change anything,” he said. “That’s ridiculous.”

The Black activist community in L.A. is “very, very complex,” said Kaya Dantzler, one of the leaders of We Love Leimert, a youth-led intergenerational group of organizers. Dantzler sees nuances of generation and ideology play out every day in Leimert Park, she said.

“You have folks who would describe themselves as anti-capitalism, and democratic socialists who are older but have a greater understanding of Black Lives Matter,” the 27-year-old said. “Then you have really phenomenal groups in Black L.A. who are organizing from a nonabolitionist lens, who are using their knowledge of the current structure system.”

Those people tend to be older community members, she said, who have been part of local institutions.

“They’re not approaching activism from a lens of ‘let’s reconstruct the system’ but more so we understand how it works, so let’s alter it,” she explained. “Then there’s a cohort of younger organizers who are no longer really concerned with figuring out how to get a seat at the table; we are more concerned with constructing a new table.”

Still, Dantzler said, older people like her grandparents believe that participating in protests “doesn’t make any sense,” she said, because they have seen it happen so many times before.

“Especially in L.A., they saw the ’92 riots and that destroyed our communities, and so for them there is a lot of wariness in seeing people take to the streets in that way,” she said. Then this month, Los Angeles officials said that they would explore cutting up to $150 million from the city’s police budget as part of an effort to reinvest more dollars in communities of color.

“It didn’t really seem like something that would be successful, but this last week has shown that it was,” Dantzler said.

At 71, the activist known as Akili likes to laugh about how he’s the “dad” among his group — some 45 years older than many of his fellow Black Lives Matter organizers.

His journey with the group began in the aftermath of the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old Black teenager shot by a white officer in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014. Mourning the loss of another Black life, Akili rented a van for a group of activists to drive to Missouri and join in demonstrations that had spilled into the suburbs and coursed through the veins of the nation.

A veteran organizer who has protested for four decades, he took the wheel for most of the nearly 2,000-mile trek and listened as the younger set in the car took turns navigating him.

“I got a chance to know a lot of them,” said Akili, who goes by his last name only. “I see myself as a bridge between yesterday and today.”

There is a perception, he added, that each generation of activists should follow the tactics of the previous one. He at times has to remind his contemporaries of the in-your-face tactics they themselves used in decades past, such as taking over university campuses to demand that they add Black studies departments.

Since the late 1960s, some activist groups such as the Black Panthers have combined an emphasis on the need for Black self-protection (including the use of armed citizens patrols) with community outreach and extensive social programs. The Black Power movement preached self-reliance and self-determination, arguing that the Black community should create its own social, economic and political power rather than looking to integrate into white society.

“Each generation will develop their own course and their own path,” Akili said. “And what I have tried to do is make some connection between some of the things we did before, and what worked and didn’t, and support them charting their own course.”

People in his generation frequently tell him that “all we have to do is talk to white leaders and they will get it,” Akili continued. Dialogue, he added, has become a buzzword — and sitting at the table has become a “fad” over the last 30 years.

He laughed, paraphrasing Malcolm X: “Just being at the table and not having a plate doesn’t make you a diner. It means you’re just sitting there.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.