He worked hard to find a job after a nonprofit paid his bail. Then the coronavirus hit

- Share via

As he reflected on the past few months, Tomajae Tolliver started by saying everything was fine. Then he paused.

Actually, he said, everything felt like too much right now. When he thought about COVID-19 and the economy and what he would do if his job didn’t call him back to work, a question looped through his mind:

“How am I going to survive?”

The 20-year-old Angeleno applied to several clerk positions and warehouse jobs last fall but almost never heard back — a silence he thinks has something to do with his September arrest on charges of misdemeanor battery. But he kept applying, motivated in part by the people he had met through a national group called the Bail Project, which paid his $41,000 bail when he couldn’t afford it.

In the weeks since George Floyd’s killing in Minneapolis, a broader swatch of Americans, including many white Americans, have begun to engage in conversations about how systemic racism shapes the criminal justice system in the U.S. The dialogue has often focused on shifting money away from law enforcement and into social services, housing initiatives and jobs programs.

But another key part of dismantling a system that disproportionately incarcerates Black and Latino men, activists say, rests in abolishing a cash-bail framework that can lock people into cycles of poverty and legal discrimination.

Because Tolliver, who is Black, got released on bail, he could focus on finding work instead of sitting behind bars as his case worked its way through the system. Eventually, Tolliver, whose charges will be dropped as long as he successfully completes a diversion program, landed a job driving a forklift for a freight company in Paramount. When his first paycheck arrived — $50 for a few hours of training and orientation — he knew it wasn’t much, but it felt good.

Then the pandemic hit.

His company cut back hours and told Tolliver it couldn’t use him right now, but that he should check back in a couple of weeks. The first several times he called, the answer was, “Not yet.”

“What’s my next move?” Tolliver said with a sigh.

Even in a thriving economy, people with arrest records often struggle to find work, and during recessions their prospects get even worse. The recent lockdowns not only shuttered restaurants and retail shops — some of the main low-wage, long-hours jobs that people with records often get boxed into — but also created a newly massive pool of Angelenos looking for work.

That means that thousands of people who were recently released from custody, including those who got out early because of how dangerous it is to be inside a packed jail or prison during a pandemic, are competing for jobs against those who may have longer work histories, no record and more education, said Bryan Sykes, associate professor of criminology, law and society at UC Irvine.

Considering the economic slowdown and the national dialogue about where we allocate taxpayer money, Sykes said he believes now is the time to redistribute funds away from the criminal justice system and toward education, social work, public health and jobs training programs. That way, he continued, when the economy rebounds, people returning from prison or jail, as well as anybody with an older record, will have more skills needed to market themselves and fully reintegrate into society.

“It’s time to do something new,” he said. “This is the moment to invest in people and not in jails and other sorts of models of social control that we have been following for the last 30, 40, 50 years.”

The pandemic has shown how quickly the system can adapt if pushed.

In early March, health officials and defense attorneys warned that conditions inside jails and prisons — double bunks, shared toilets, limited soap — laid the perfect groundwork for coronavirus hotspots. Soon, inmates across the country started to die of complications of COVID-19, and lawyers for the state of California announced in late March that they intended to release 3,500 inmates early.

In an effort to thin out jail populations, the state’s judicial council set new emergency rules in April that reduced bail for misdemeanors and some felonies to zero. (The judicial leaders rescinded the $0 bail policy in June.)

“If we can release people when there’s a health crisis coming, why couldn’t we to begin with?” asked Robin Steinberg, who founded the Bail Project, the first community bail fund of its scale in the nation, which now operates in more than 20 cities nationwide, including Compton.

Launched in 2017 as an outgrowth of a bail fund Steinberg started in the Bronx a decade earlier, the national nonprofit operates from the ethos that cash bail perpetuates a two-tier system, which upholds economic inequality and structural racism. Bankrolled by philanthropists, the Bail Project publicly advocates for nationwide reform — the goal, Steinberg said, is to “ultimately put ourselves out of business.” But until that’s a reality, she said, they’re dedicated to securing pretrial freedom for as many people as possible.

While the emergency releases during the pandemic have shown what is possible, Steinberg stressed that sustained change will require systemic reform.

And it’s long overdue, because cash bail is simply unnecessary, Steinberg said. Since the fall of 2018, when the group opened its Compton site, it has paid bail for 130 low-income clients. In 96% of cases, those clients have returned for their court dates.

In recent weeks, Steinberg said, she has felt deeply hopeful, as two concepts her group has long advocated for — shrinking the incarcerated population and shifting money from policing and prisons into direct community investment — have gained broader public traction.

During the past few weeks, as people protested across the country following Floyd’s killing, the organization has brought in more than $15 million in donations from some 200,000 people, funds that Steinberg said will go toward securing pretrial freedom for tens of thousands of people and working to pass bail reform in every state.

Some jurisdictions, including New Jersey and Washington, D.C., have largely abandoned the use of cash bail. In other places, including California, efforts to abolish it have hit powerful pockets of resistance. Almost as soon as then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed a landmark law two years ago abolishing cash bail, a coalition of bail-bonds industry groups started collecting signatures for a referendum, which froze the status quo in place. (The issue will now go before voters in November.)

The current moment feels distinct, Steinberg said, noting that more Americans now seem to be connecting the dots from slavery to Jim Crow laws, which codified the segregation and disenfranchisement of Black people, to the current disproportionate imprisonment of Black men. More people seem engaged, she said, in pursuing alternatives to incarceration that focus on community investment.

“There is finally an appetite,” she said, “to move away from using handcuffs and jail cells and patrol cars to solve our social problems like poverty and systemic racism and lack of access to healthcare.”

::

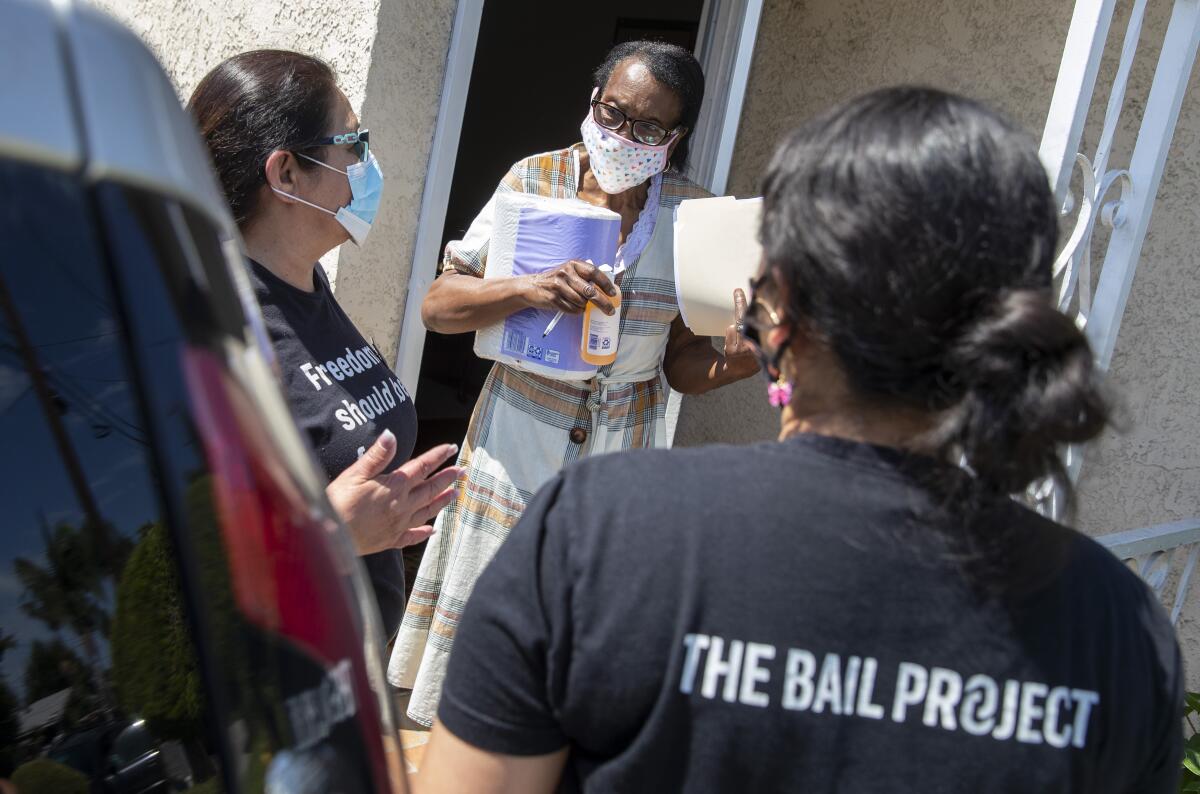

On a recent Wednesday morning, Dolores Canales, who handles community outreach for the Bail Project, met up with co-workers and volunteers from other local groups focused on healthcare and ending mass incarceration.

The group members, all wearing masks, were preparing to drive in a caravan to drop off supplies, including toilet paper, $25 Target gift cards and packets of information about COVID-19 testing sites, at the homes of several Bail Project clients, including Tolliver.

Before they left, Canales told a short story about her son, who is now behind bars. When he was 6 years old, she took him to a park in Placentia and they splashed around in a fountain. Off in the distance, she spotted a police officer pulling up on a motorcycle and looked down at her son, who was clinging to her and shaking.

His young mind, she realized, was flashing back two years to when he watched police officers kick in the door of her godmother’s home and slap handcuffs around Canales’ wrists.

“He never got to experience law enforcement as a protector,” she said. And her memory of that day in the park is one of many reasons why she’d like to see policing as we know it dismantled so more money can be invested directly into communities.

Finding a support system made all the difference in her own life, Canales said. In 2001, when she was arrested on a drug charge, she faced up to life in prison under California’s three-strikes law, because of her earlier record, which included a residential burglary from when she was a teenager. Friends in the recovery community reached out to her, and when she bailed out with money from a relative she immediately checked herself into a recovery home in Fullerton to focus on staying off heroin.

Ten months later, when she turned herself in to serve her prison sentence, she had a deep community of support, including a group of women who took her to Knott’s Berry Farm on her final night of freedom to conquer her fear of the GhostRider rollercoaster.

She stayed in touch with many of them during her seven years behind bars, and they helped her, again, when she had nothing to her name but the $200 she received from the state of California upon her release. Friends let her sleep at their homes, as she applied to jobs at Rite Aid and a nursing home.

But she didn’t hear back, so a friend hired her to work as a part-time caregiver for her bedridden mother. Eventually, her cousin helped her get a job at an interpreting service.

“It wasn’t the system we’ve created through probation and parole and law enforcement that did anything for me,” Canales said. “It was all community. People who invested in me.”

On the recent Wednesday morning, after driving to Tolliver’s home, Canales waved from afar when she spotted Tolliver and his girlfriend standing on the porch.

“How are y’all doing?” Tolliver asked.

“How are you?” Canales said, as her co-worker handed Tolliver two boxes of diapers for the baby the couple is expecting this winter.

“Wow,” he said softly. “I appreciate it.”

“No,” Canales said, “we appreciate you.”

The Bail Project’s investment in his life has helped him stay motivated, Tolliver said. “You see that not everybody is mean. Some people are here to help.”

Tolliver invited the group inside and they all stood in a semi-circle. Everyone did their best to stand several feet apart, save for the moment when Tolliver’s girlfriend, Katherine Cordova, teared up in gratitude and a few quick hugs were exchanged.

Tolliver told the group that he had called his job the previous day, but that the freight company was moving slowly and didn’t need him yet. Cordova, chimed in, saying that after being furloughed for several weeks, the restaurant where she works had called to say they could use her back.

To pass the time in recent days, Tolliver cleaned the house and helped babysit his nephews. He followed the news of the protests after Floyd’s death and hopes for true justice, but he decided not to join protesters. Especially when there were curfews in place, he said, he wanted to avoid any opportunity to come into contact with the police.

“I’m just laying low,” he said.

On days he felt discouraged, he repeated two sentences in his mind — “Keep your head up. It’s just the beginning.”

Then, a few days ago, he called work again, just to double check. This time, he said, they told him they could use him back in the warehouse.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.