For contact tracers, COVID-19 fight is personal: ‘I understand hardship’

- Share via

Sometimes when he calls, the person on the other end of the phone already knows.

I’m not surprised.

Sometimes, they deny the news.

This is a hoax.

Often, they reel from it.

I can’t afford not to work.

Though each conversation differs, the disquieting messages Levonn Gardner delivers are the same.

“You have been exposed to the coronavirus,” he tells some. “You have tested positive for the virus,” he tells others.

Gardner is a contact tracer, part of an army of hired public health workers who notify those who have tested positive for the virus and identify those they may have exposed to the pathogen that causes COVID-19.

The conversations are confidential and sometimes surprisingly intimate. Some last minutes, others hours. And as Gardner and two other contact tracers shared, much of the job relies on intuition shaped by cultural and familial ties — bonds that make the work personal.

“I understand hardship,” said Gardner, a 39-year-old Marine Corps veteran. “I understand what it means, especially, because it is primarily the Black and Latino communities that are dying from this and getting sick. It’s people from my community.”

Before data underscored how marginalized communities were disproportionately hit by the virus, which has killed at least 7,700 in Los Angeles County, Gardner knew. A contact tracer with the county Department of Public Health, he didn’t need to see the numbers or be told by officials to understand the reality he was hearing on the phone.

“I’m a Black dude from Watts, so my view is: Anything bad that happens hits the poor communities harder.”

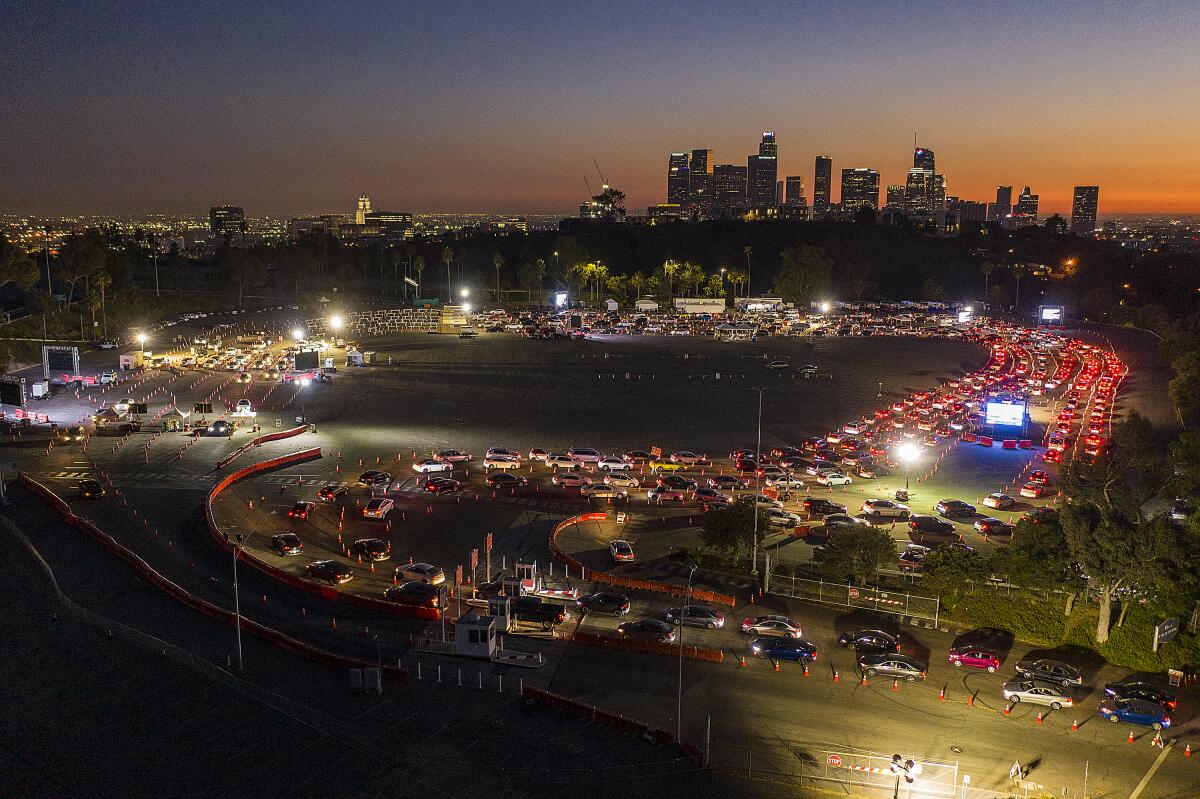

On Tuesday, the county reported its highest number of new coronavirus cases and hospitalizations ever experienced during the pandemic — an indicator that the virus is spreading at alarming speed. Tracers face immense pressure when infections are surging — as they are now in California and elsewhere. When a backlog in cases has been reported, the window to contact someone before the potential incubation period is over narrows. Some have been overwhelmed; others have given up.

California has poured more than $27.3 million into contact tracing efforts. According to the state’s Department of Public Health, about 10,600 city, county and state employees are trying to track the disease through the state’s California Connected program.

The work requires patience and perseverance. In L.A. County, an average of 63% of people who tested positive for the virus and 71% of their contacts agreed to complete an interview over a seven-day period from Nov. 11 to Nov. 17. Hang-ups happen, and some argue that the virus isn’t real.

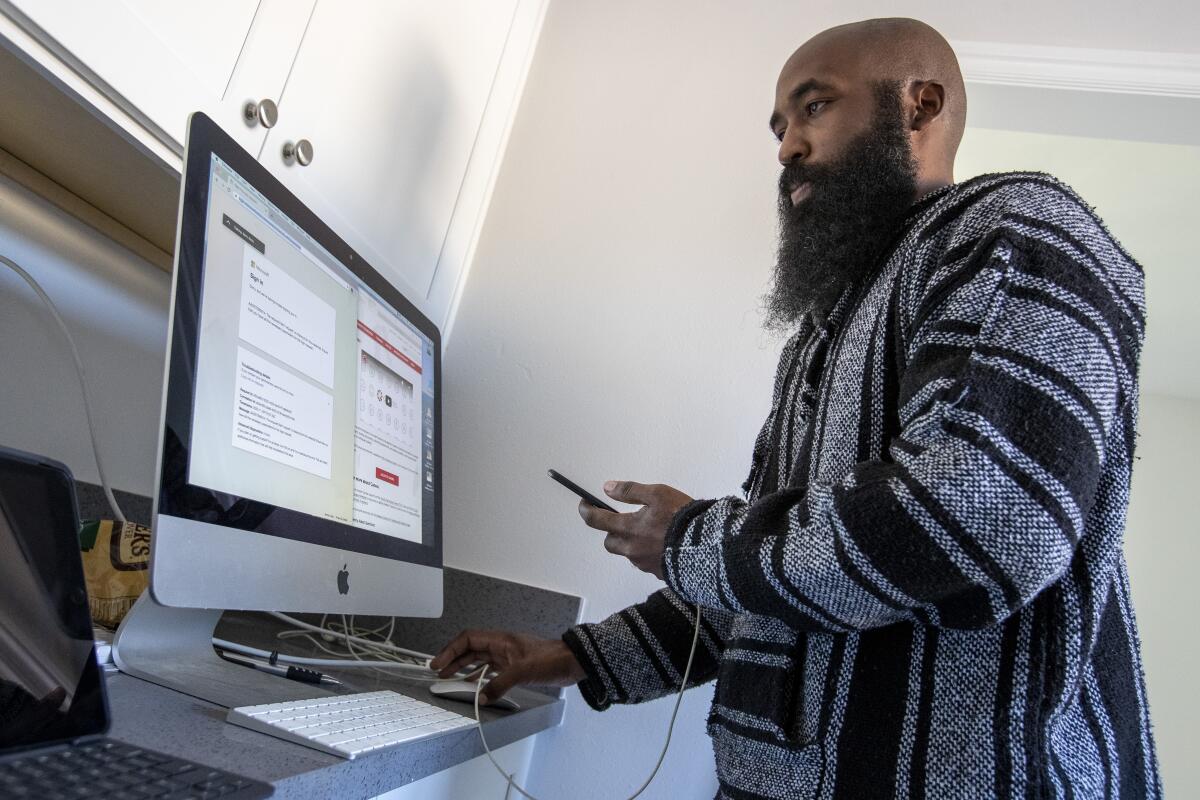

Those who do answer the phone often experience great anxiety brought on by anticipation of the unknown. Gardner, who is working remotely from his kitchen, recalls speaking to a Latina who was an essential worker and a mother. She understood that she needed to self-isolate but couldn’t fathom the loss of a paycheck for two weeks. Gardner wondered what other responsibilities would be affected if she were to get sick.

“Does she live with her parents? How young are her kids? You can’t completely leave a 6-year-old child by itself. Even if you were exposed, you need contact,” he said.

Librarians and other library staff in Los Angeles are becoming contact tracers.

Empathy is crucial in gaining a person’s trust, Gardner said, and some people are naturally skeptical about speaking with tracers. To encourage Angelenos to participate in contact tracing, the county began offering $20 gift cards to those who complete the process.

The tracer asks where the person has been, offers tips to safely quarantine, answers questions and listens to myriad fears about a disease that has killed more than 268,000 in the U.S. and has left millions of lives hanging in the balance. The process is repeated once, twice, multiple times until it’s time to stop for the day and prepare for the next.

Recently, health officials launched a method for people who test positive to immediately and anonymously alert contacts via their mobile phone by clicking a link from their electronic notification.

Gardner has made hundreds of calls to infected or potentially infected individuals since he became a contact tracer last spring. When the county began its tracing program in April, there were 500 workers. There are now 2,600.

Most, like Gardner, were reassigned by other county departments to assist in one of the state’s key efforts to mitigate the spread of the novel coronavirus. Gardner previously worked solely in the county’s division of HIV and STD program.

“Civil servants in the county all agreed that if there was ever a disaster, we were going to work it,” said Roberto Melendrez, 54, who has overseen a team of tracers in L.A. County for months.

You go through this very intense, intimate conversation with a group of people, and then you say goodbye.

— Roberto Melendrez

Conversations stick with him: The homeless man who answered his call outside a liquor store and understood that he needed to stay away from people but said he couldn’t afford not to keep collecting recyclables. The teenager who had become the caregiver for an infected parent. The guilt-ridden nursing home attendant whose husband and son got sick before she did.

“You go through this very intense, intimate conversation with a group of people, and then you say goodbye,” Melendrez said.

Once, he called a woman to warn her to quarantine, but she already knew that she had been exposed.

“My mother just died this morning from COVID-19,” she told him.

Then there was the time he contacted 12 people in a multigenerational family that included parents, in-laws, children and grandchildren.

As he started making phone calls, he realized that all 12 were living under the same roof. As the news spread, Melendrez could hear the family members gather. Those who awaited contact anxiously questioned one another in the background; those already in the know shouted answers.

The goal is to reach a person before it’s too late to offer help. That can be difficult when people are wary to pick up calls from unknown numbers. One of Melendrez’s rules is to never hound a person or bombard them with voicemails — you never know what someone is going through in a given moment, he said, and adding to their stress should always be avoided.

The script that Melendrez and other tracers use as guidance for their conversations started as half a page. It’s now 15 pages long, a living document that has evolved as health orders have changed and knowledge of the virus has expanded.

The outline guides tracers’ questions but doesn’t dictate their conversations. Much of the back-and-forth relies on an individual tracer’s perception.

For example, Melendrez, who was born and raised in East Los Angeles, recognized early on that using residencia — Spanish for “home” — may bring a fear of immigration services for some Latino residents. He changed the phrase to domicilio, a softer way to ask where a person lives.

“That’s a lot less threatening.”

The crime-tracking app Citizen has been criticized for encouraging overpolicing. L.A. chose the company behind it to do COVID-19 contact tracing.

Allison Wong, 30, realized on Day One of the job that essential workers who were disproportionately of Spanish-speaking and Cantonese-speaking backgrounds were those most at risk for contracting the virus — and often the people least able to stop working.

“It was really important to me personally to reach out and offer support — both information and services — to these populations that are, after all, risking their lives for service,” said Wong, a UC San Francisco medical student who works part time with the city’s Department of Public Health.

Wong, who has worked as a contact tracer since last spring, has learned that listening is just as important as providing information. She too has heard from people who feared that loss of work would upend their lives and those of the families that depend on them.

Then there are those with few options, like the infected person who lived with a dozen roommates in a two-bedroom apartment. How to self-isolate? Wong provided contacts for a staffer who helps place people in hotels.

“At the end of the day, we try to offer as much as we can. In some cases, that may not be enough,” she said.

Wong has felt the impact of the pandemic too. Though she feels fortunate by comparison with others who have lost loved ones or have suffered from the virus, she misses her dad. One of the hardest adjustments has been her inability to see him regularly and sit down with him to enjoy a meal he’s cooked — one of his favorite displays of love. She’s visited him three times at a distance, but her father is high-risk — a fact she can’t ignore.

Before California moved most of its 58 counties backward in its color-coded reopening blueprint, San Francisco was one of the few areas that had reached the least restrictive tier. Wong attributes some of that success to tracing efforts and the many services offered during contact, including mental health resources, quarantine options for relocation — and translation services.

Many of Wong’s elderly relatives speak only Cantonese. That insight helped her understand quickly that educational resources were crucial for residents who didn’t speak English, especially those within the Asian community — a group targeted by discriminatory bias when the virus first hit the U.S. The dual need to educate the masses and combat rumors became apparent.

“The Cantonese population here in San Francisco has limited English proficiency, so I think that’s a really fertile environment for misinformation to spread,” she said, emphasizing that her ability to help her community is a big reason she is committed to the work.

Gardner too saw the negative effects of misinformation in the early days of the pandemic. He also points to systemic racism and historical mistrust, highlighting the U.S. government’s infamous Tuskegee syphilis study in Alabama that used sick Black men for experimentation from 1932 to 1972. Such a history, he said, explains why the virus wasn’t initially taken as seriously by some in the Black community.

Black Americans have been hit hard by the virus. It’s a major reason he’s committed to reaching out and sharing the facts, whether with strangers over the phone, his friends in Watts or his mom, a Metropolitan Transportation Authority bus driver on a different kind of coronavirus front line.

Tracing work can be taxing. But Gardner, like others, is in it for the long haul.

“I’m here until they need me to do something else.”

The tracers’ mission is to gather information. But sometimes they find themselves confiding personal details to those they call. Sometimes, the revelations are to gain trust, but sometimes it just feels right to share, to reveal.

Melendrez has told his contacts he knows all too well how the coronavirus can rip families apart. His 94-year-old father died of COVID-19.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.