- Share via

Pinned to the ground by the cop who lived across the street, Daniel Garza tried to mentally prepare for the moment his wrist would break.

The pain was already intense. What would it feel like if his wrist actually snapped?

“I was trying to be a man and trying to hold in the pain, but, man, that wristlock hurts,” Garza recalled. “He’s just bending it and bending it.”

What preceded the altercation between Garza and his neighbor, Los Angeles Police Sgt. Mario Cardona, was a family drama involving Cardona’s stepdaughter, whom Garza had dated. She claimed that Garza had briefly kidnapped her — which he denies.

What has happened in the more than five years since is a whirlwind of litigation and bureaucracy.

Garza alleges that the Los Angeles Police Department stood behind its officer instead of standing up for justice, and Cardona alleges that the city of L.A. threw him under the bus.

What’s clear is only this: If you sue a cop in L.A. for excessive force, you could be in for a wild ride.

“This is the problem with the LAPD,” said Jim DeSimone, Garza’s attorney. “This is why people are out on the streets.”

According to court records, Garza and Naomi Villanueva, Cardona’s stepdaughter, had argued in the days leading up to the altercation.

Villanueva had moved out of her parents’ home — across the street from Garza’s house in Whittier — and in with a friend about 20 minutes down the road in Downey. She had dated Garza for about two years — starting after she’d turned 18, when he was in his mid-20s — but their relationship was on the rocks.

Villanueva would later testify that Garza showed up to the Downey home one night in May 2015 about midnight and saw that she and her roommate were hanging out with other guys; Garza got angry and accused her of cheating on him. Villanueva said that when she went outside to try to calm him down, he grabbed her by the arm, walked her to his car and drove her back to Whittier.

Garza disputes that account. He acknowledges going to the Downey home but said it was an emotional Villanueva who followed him outside and jumped in his car after he told her their relationship was over. He said it didn’t make any sense that he would “kidnap” Villanueva, only to drive her to her parents’ house.

Either way, Villanueva’s parents were upset, and her mother, Cherie Cardona, also a law enforcement officer, reported the incident to the Downey Police Department, law enforcement records show.

Several days later, on May 14, 2015, LAPD Officer Mario Cardona, then 41, arrived home in his truck and spotted Garza, then 26, in his own yard across the street, exercising with a Pilates band.

Garza said Cardona immediately started walking in his direction, “just staring me down,” then ordered him to come onto the street. Garza said he complied because Cardona was a police officer, and Garza thought he “had to listen to him.”

Once he’d stepped off his property, Garza said, Cardona started punching him.

Cardona told a different story in court. He alleged that Garza had swung first, after some trash talk. Cardona said he had acted in his capacity as a police officer when he arrested Garza on suspicion of assault and believed a kidnapping warrant had been issued based on his wife’s complaint in Downey. He said he never punched Garza but used a leg sweep to take him to the ground and the wristlock to keep him there — just as he’d been trained by the LAPD.

But at least one witness backed Garza’s version of events.

‘They had made up a story of what had happened to make him look like a hero and me look like a criminal.’

— Daniel Garza

“I saw [Cardona] as the aggressor, swinging and punching Daniel, who was ducking his head, taking more of a protective stance trying to protect his head from being struck,” a neighbor, Ramsey Muro, later testified.

Once Garza was on the ground, Muro said, Cardona “just sat on top of him, just continued to swing.”

Video from the scene shows Cardona straddling Garza and applying the wristlock — a move Cardona’s commanding officer, Edward Prokop, said during a later deposition was unreasonable.

Garza screamed in pain.

“Mario, let me go!” he yelled. “I’m not resisting!”

- Share via

If you sue a cop for excessive force in L.A., you could be in for a wild ride.

When Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies arrived, Cardona was still straddling Garza, who by that point was handcuffed. Cardona identified himself as an off-duty LAPD officer and said he was arresting Garza because he was wanted by the Downey police on a kidnapping charge.

But there was no kidnapping charge.

When the deputies called Downey police for information, a sergeant said that Cherie Cardona had filed a kidnapping complaint based on “secondhand information” and that Villanueva had not wanted Garza to be prosecuted, according to a sheriff’s report.

There was no warrant for Garza’s arrest, even if Mario Cardona believed there was.

Deputies took the handcuffs off Garza and listened as he described Cardona punching him repeatedly and pinning him with the wristlock.

A deputy wrote that he observed redness on Garza’s face, bruising and abrasions to his knees and redness on his wrists.

Deputies said they told Garza he was not under arrest, but he was nonetheless left in the back of a squad car as they turned their attention to Cardona — whom they were treating very differently.

Cardona asked that he not be questioned until his supervisors from the LAPD arrived, and the deputies agreed. When the supervisors arrived, they all went into Cardona’s house to discuss what had happened, leaving Garza to wait in the squad car.

At the time, Garza thought Cardona might be getting arrested, but when the LAPD supervisors and sheriff’s deputies came out, it was with a bunch of reasons why Cardona was in the clear — including the fact that his supervisors had retroactively changed Cardona’s status at the time of the takedown from “off duty” to “on duty.”

Garza had a different take: “They had made up a story of what had happened to make him look like a hero and me look like a criminal.”

So he filed a complaint.

Cardona has said it made sense for him to be placed on duty because he had been acting as an officer when he made what he felt was a legitimate arrest for two reasons: Garza’s alleged assault on him (which Garza denies) and his mistaken belief that Garza was wanted on a warrant.

Nine months later, Garza received a letter from then-Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck and Capt. Greg McManus, another commanding officer, in which they were unequivocal: After “several levels of review,” LAPD internal investigators found that Cardona had done nothing wrong.

“Your allegation that an officer twisted your wrists causing pain was classified as Exonerated, which means the investigation determined that the act occurred, but was justified, lawful, and proper,” the commanders wrote.

Cardona would not be punished.

Three months after receiving the letter, in May 2016, Garza filed a federal lawsuit against Cardona, Beck and the city of Los Angeles, alleging false arrest, unreasonable search and seizure, excessive force, assault and battery, negligence and intentional infliction of emotional distress.

The lawsuit asserted that Cardona had been working as an officer during the encounter and used that authority to prevent neighbors and even a sheriff’s deputy from interfering. It recounted one passerby saying, “That looks like it hurts,” as he videotaped Cardona twisting Garza’s wrist, and Cardona responding, “It does, now get back.”

The lawsuit noted that another judge had already granted Garza a three-year restraining order against Cardona, having found “clear and convincing evidence that [Cardona] was the aggressor and that he engaged in assaultive conduct.”

And it said Beck’s failure to impose discipline on officers like Cardona had created “a culture of impunity within the LAPD that encourages such violence and incidents of unreasonable force against the public.”

As the case headed to trial, both Cardona and Garza wanted certain information on the record, but for different reasons. Two examples: the internal affairs investigation and the decision by Cardona’s supervisors to consider him on duty after the incident occurred.

Garza thought internal affairs documents showed that the city and the department were complicit in what happened. Cardona felt they showed he had acted appropriately as an LAPD officer, not as the angry stepfather of Garza’s ex-girlfriend.

In both their minds, there was no question that Cardona had acted as a cop.

However, the city attorney’s office held a different view.

The city’s position was that the documents should not be admitted because they would prejudice the case by making jurors believe that Cardona was acting as a cop, when he was not. City attorneys argued that the LAPD “does not hire and train its police officers to assault members of the community while off duty.” They also argued that internal affairs investigators had not witnessed the incident, and therefore “any conclusions or inferences that might be drawn from those reports would constitute lay opinions that are themselves inadmissible.”

That city attorneys would dismiss the findings of LAPD internal affairs investigators — whose opinions they rely on in other cases — astounded Garza and DeSimone. But it worked.

Presiding U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson ruled that the information was inadmissible. The jurors wouldn’t hear it. Instead, they heard from then-Deputy City Atty. Michael Amerian, who — speaking in defense of the city — slammed Cardona as an off-duty officer who’d lost control in his personal life.

Amerian, now a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge, called Cardona’s actions “despicable” and “so vile, base or contemptible” that they would be “looked down on and despised by reasonable people.”

“If that isn’t malice, I don’t know what is,” Amerian said.

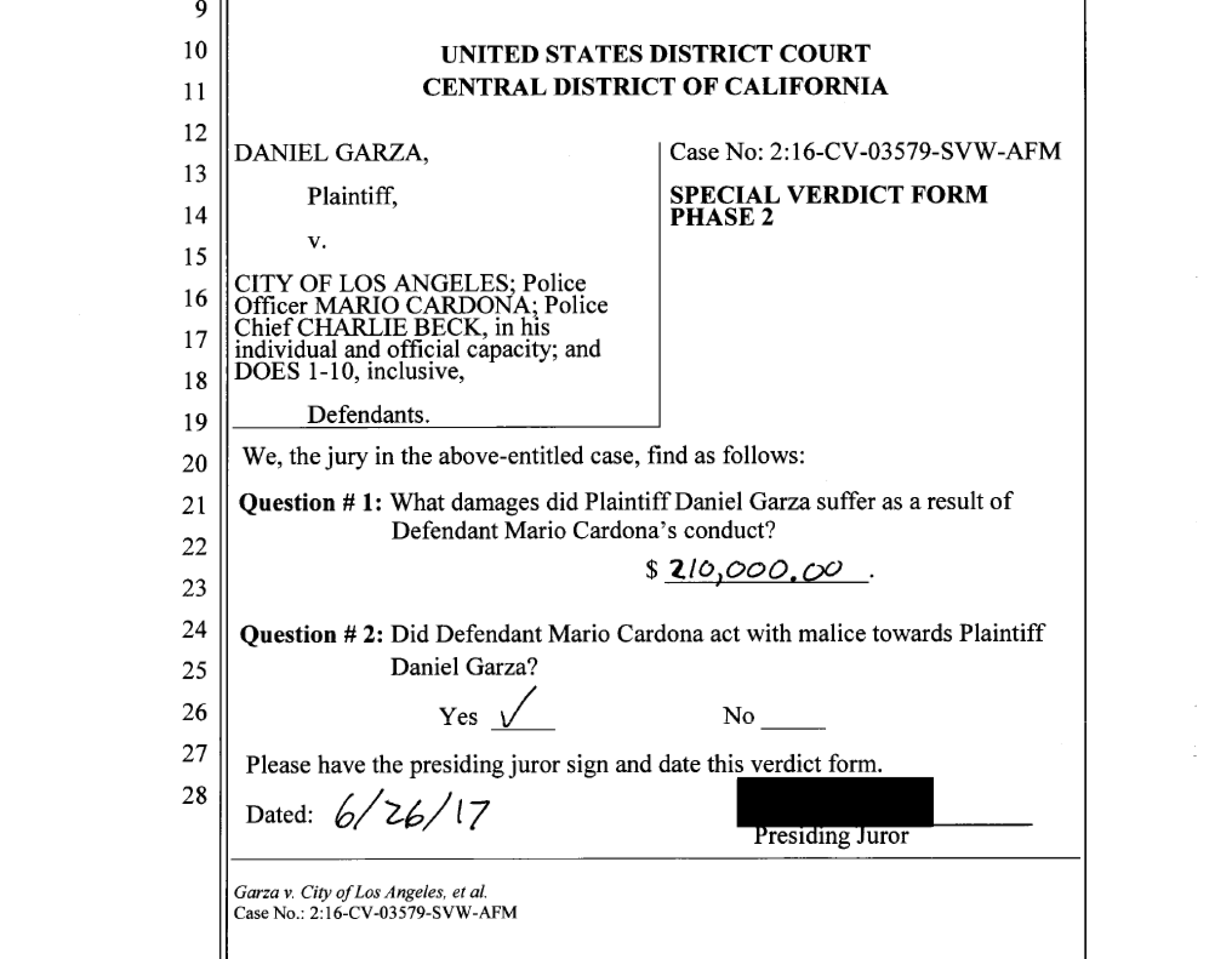

The jury agreed, finding that Cardona had acted with malice toward Garza. On June 26, 2017, they ordered him to pay Garza more than $200,000 in damages, in addition to more than $600,000 in attorney fees and other costs. Cardona’s total debt in the matter was nearly $900,000.

The city, on the other hand, wouldn’t have to pay a dime.

Even though Cardona had used his badge to justify his actions, and the LAPD had cleared him of wrongdoing, the jury’s finding that he’d acted with malice allowed the city to avoid liability in the matter. Beck had been dismissed from the case earlier.

Rob Wilcox, a spokesman for City Atty. Mike Feuer’s office, said in a recent statement to The Times that Cardona had “acted on his own.”

“Certainly taxpayers should not have to foot the bill for such conduct,” Wilcox said.

In an interview, Cardona said the city attorney’s office had indemnified other officers who were sued for off-duty incidents and was wrong to refuse to cover him — especially since the LAPD had cleared him of wrongdoing.

“I was thrown underneath the bus by the city attorney’s office,” Cardona said.

Wilcox said the city attorney’s office had “taken appropriate and consistent positions throughout this litigation.”

More than three years later, Garza — now working as a teacher — has not been paid.

Without support from the city, Cardona filed for bankruptcy, trying to have the massive debt he owes to Garza discharged.

That effort was recently rejected, when the Bankruptcy Court found that the law does not allow debtors to discharge debts stemming from their own malicious actions. In July, the court tallied Cardona’s standing debt in the matter at $899,267.87.

Cardona, now a sergeant in the 77th Street Division, did not respond to a request for comment on the effects the case has had on his family and finances.

In the meantime, litigation has continued.

After it was revealed that Beck had signed off on Cardona’s promotion to sergeant just weeks after the jury’s finding that Cardona had acted with malice toward Garza, the issue of liability on the city’s part was taken back up in a second trial in July 2019.

Garza and DeSimone argued that the promotion showed that the city and department approved of Cardona’s malicious actions. City attorneys, who agreed that Cardona acted with malice, pushed back, arguing that his promotion had been in the works before the malice verdict; Beck had merely signed off on it as part of a lump approval of hundreds of promotions.

The jurors in the second trial were told to narrowly consider the issue of whether the promotion showed city approval for Cardona’s actions. But they weren’t given all the preceding facts, after the presiding judge again deemed certain information inadmissible. The jurors weren’t told about the letter Garza received from Beck’s office saying Cardona’s actions were justified, nor that Beck in an earlier deposition had acknowledged discussing the malice verdict with colleagues before signing off on the promotion.

Partially in the dark as to that history, the second jury ruled for the city, too. Again, the city would not have to pay.

Garza appealed, arguing that the District Court had “abused its discretion by allowing the City to play fast and loose with the facts.”

In November, a three-judge panel of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments in the case from DeSimone and Deputy City Atty. Michael Walsh.

DeSimone argued that the lower court erred in not allowing him to show the second jury more evidence, that Beck had clearly approved of Cardona’s actions by signing off on his promotion and that the city had been disingenuous throughout the case by shifting its position on Cardona’s actions.

Walsh argued that the case had been properly decided in the lower court and that Beck had approved the promotion as a pro forma administrative action at a time when he felt he had no legal recourse to do otherwise. It was perfectly reasonable, Walsh said, for LAPD internal affairs and attorneys working for the city in a civil lawsuit to reach different conclusions about Cardona’s actions.

The judges largely focused their questions on Beck’s approval of Cardona’s promotion but also seemed incredulous about Walsh’s explanation for how the LAPD and the city attorney’s office could have such a different understanding of Cardona’s actions.

“Do you think it was a little disingenuous,” Judge Johnnie B. Rawlinson asked, “for the city to take a position in one proceeding that the acts that were engaged in by the officer were malicious, and then on the other hand say that they were in [line] with the policy of the city?”

A decision in the case is pending.

Experts say the case raises important questions about when officers should be indemnified and how such cases should be litigated by cities — an especially volatile topic amid mass protests against police brutality.

“The idea that the city, in making its indemnification decision, can make one determination, and the police department can make another — it doesn’t make logical sense,” said Joanna Schwartz, a UCLA law professor who studies police accountability. “It makes strategic sense, but I don’t see how the city could justify those two decisions.”

Garza said it reveals hypocrisy in city government and a willingness by LAPD commanders to turn a blind eye to abuse.

Cardona thinks it’s all unfair — to him.

After all, he asks, how could the city attorney maintain he wasn’t on the job? After the LAPD declared he was on duty that day, he was put on the clock and paid overtime for his efforts.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.