L.A. has avoided a New York-level COVID-19 hospital meltdown as conditions improve

- Share via

Just weeks ago, Los Angeles County’s hospitals were overwhelmed and on the brink of a worst-case catastrophic scenario, with plans ready if doctors needed to ration healthcare.

But with the region now in its fourth week of declining hospitalizations, it was clear Wednesday that the county was decisively on its way out of its third surge of the pandemic, its deadliest yet.

Yes, hospitals this week are still under pressure — scheduled surgeries are still suspended, and there’s still a shortage of medical staff, with hospitals relying on nurses drafted from clinics, contract agencies and the federal and state governments. L.A. County’s hospitals are still under great strain, with nearly three times as many COVID-19 patients as it did during the peak of the summer wave. The state has opened up two surge hospitals — in Sun Valley and Hawaiian Gardens — that have been used to relieve the strain on other facilities.

And conditions could still worsen, given the rise of mutant variants of the coronavirus circulating in California, one of which is believed to be more contagious and deadlier than the conventional variety. That variant, first identified in Britain in September, is rapidly spreading in the U.S. and could become the dominant variety of the coronavirus by March, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Local officials warn the mutant strain has the potential of triggering a fourth wave of the pandemic later this winter if people stop wearing masks, stop practicing physical distancing and hold large, crowded Super Bowl parties, much as they did for the NBA Finals and World Series that fueled the autumn-and-winter surge.

Yet L.A. County health officials this week were clearly relieved that they had managed to avoid a northern Italy and New York City-style disaster in the hospitals from the third surge of the pandemic, the worst by far.

Scientists thought the U.K. variant was more transmissible, but evidence suggests those who have the virus are also more likely to die from it, Dr. Anthony Fauci says.

There were no hospitals in a declared state of internal disaster, a change from weeks ago. No hospitals have been forced to formally declare to county officials they were providing “crisis standards of care,” which includes being so overwhelmed that doctors would be forced to decide which patients would receive the most aggressive lifesaving treatment and which patients would receive only palliative care as they died.

At the worst of the crisis, virtually all hospitals were forced to divert some ambulances away on a daily basis; now fewer than half need to do so any given day, Dr. Christina Ghaly, the L.A. County health services director, said.

“The case numbers are down. The hospitalizations are down,” Ghaly said Tuesday. To be sure, it will take time for the number of people in hospitals to decline. “But [the numbers] are absolutely heading in the right direction.”

The number of new patients hospitalized with COVID-19 daily in L.A. County is now about 500 a day — much better than the peak of about 800 a day earlier this month, but still far worse than the summer peak of 250 new hospitalizations a day, according to data Ghaly presented at a briefing Wednesday.

The total number of COVID-19 patients in hospitals in L.A. County on Tuesday was 6,026; that’s down 25% from the high of 8,098 recorded on Jan. 5. But Tuesday’s number is still far worse than the peak from the summer, when 2,232 were in hospitals with COVID-19.

L.A. County is now averaging about 7,600 new coronavirus cases a day over the past week — far better than the 15,100 cases a day recorded for the seven-day period that ended Jan. 13, according to a Times analysis. The daily case rate, however, is still much worse than what was observed in mid-October, when fewer than 1,000 new cases a day were recorded on average.

Daily COVID-19 deaths are still expected to remain high for a couple of more weeks. On Wednesday, 301 more COVID-19 deaths were tallied in L.A. County, the second-highest single-day tally on record, just below the high of 318 deaths recorded each on Jan. 8 and Jan. 12. L.A. County is averaging 214 COVID-19 deaths a day over a weekly period, an improvement over the record average of 241 deaths a day for the seven-day period that ended Jan. 14.

The trend is reassuring, “so I do think that it’s appropriate at this point to start loosening the restrictions,” Ghaly said.

L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said she’s pleased and grateful for all the work that so many L.A. County residents have done to stay at home as much as possible and wear masks. But she warned, “we do need to move through the next few weeks with a lot of caution.”

“All of us know that at many other points [earlier in the pandemic] where we’ve been reopening our sectors, we in fact have seen a bump up in our cases. We can’t really afford that,” Ferrer said. “So I’m going to ask everybody to be extra diligent this time around, because our case numbers are still much higher than they’ve ever been before — except for the month of December and January.”

Compliance with health orders will be key, and health inspectors will be out and ready to issue citations if there are any violations, Ferrer said.

Her warnings were echoed by L.A. County supervisors, who, like health officials, are eager to avoid a backsliding of the pandemic that would probably force a new round of business closures.

“As restaurants are allowed to reopen, or nail salons — if you are in a high-risk category and you have not been vaccinated, you need to continue to take all precautions, especially knowing that the numbers are still somewhat high, and that we’re not out of the woods,” Supervisor Kathryn Barger said. “We cannot let our guard down.”

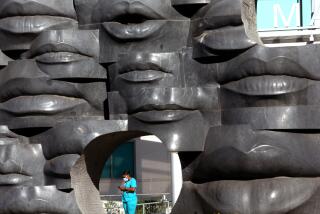

To contain the spread of COVID-19, parks, restaurants and stores are slowly reopening.

Vaccinations alone won’t be enough, Barger said, and she urged people to continue wearing masks, practicing physical distancing and limiting contact with large crowds.

Epidemiologists credit the cumulative effects of the outdoor dining ban and the stay-at-home order for blunting the worst impacts of the surge. In the end, it took roughly two months for the orders to have convincingly turned the surge around and begin observing sustained reductions in COVID hospitalizations and giving officials confidence to reopen businesses — about the same time it took for business restrictions to work over the summer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.