Column: The ghosts of migrant dead haunt California. Let’s honor them

- Share via

In 1948, a plane crashed in Los Gatos Canyon near Coalinga, killing 28 laborers getting sent back to Mexico. In the Salinas Valley town of Chualar a freight train tore through a flatbed truck in 1963, leaving 32 braceros dead in its wake.

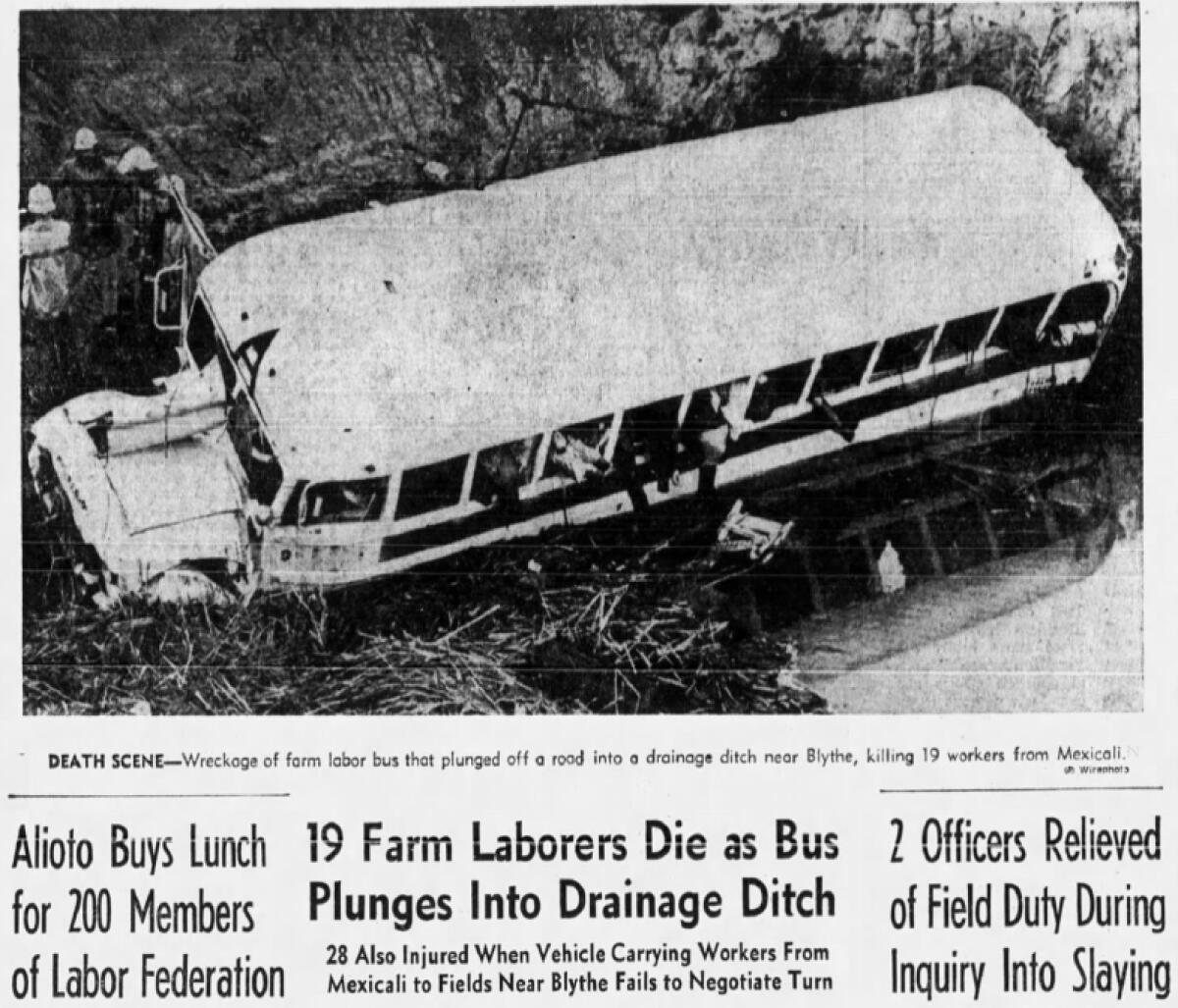

Just outside of Blythe, 1974: 19 field hands drowned when their bus plunged into an irrigation canal. In 1999, 13 tomato-sorters packed into a Dodge Ram perished after their van crashed; the muddy boots of the corpses peeked out from sheets as responders tried to identify them.

For the record:

11:26 a.m. March 7, 2021An earlier version of this article said the plane crash in Los Gatos Canyon occurred in 1945. It was 1948.

March 2, 2021: A big rig slams into a Ford Expedition with 25 people crammed inside near the Imperial Valley town of Holtville. Thirteen dead Mexican and Central American immigrants.

Ghosts, so many ghosts.

These migrant dead haunt California, like an Edgar Allan Poe horror story. They wander the border and farms, linger on the side of roads and in overcrowded spaces. Forgotten cogs of the Golden State machine, a land where Latino labor has always been simultaneously essential and expendable.

We stop and hand over a pinch of our attention, like tithing on Sunday, when the number of dead is too large to ignore.

Woody Guthrie wrote one of his most moving songs “Deportee (Plane Wreck at Los Gatos)” after he heard a radio broadcast’s dismissive descriptions of the Mexicans onboard the ill-fated flight.

Goodbye to my Juan, goodbye, Rosalita,

Adios mis amigos, Jesus y Maria;

You won’t have your names when you ride the big airplane,

All they will call you will be “deportees”

The 1963 Chualar tragedy helped dissolve the bracero program, the binational agreement between the United States and Mexico that legally brought in millions of Mexican men to work in agriculture but which activists decried as codified serfdom.

At a funeral Mass for the 1974 Blythe bus disaster, Cesar Chavez told a crowd of 4,000: “It is our obligation — our duty to the memory of those who have died — to see to it that workers are not continually transported in these wheeled coffins, these carriages of death and sorrow.”

Right now, the newest migrant ghosts look upon crosses crafted from cedar door shims that bless both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border in their honor. Painted and pasted on by refugees and deported people based in Tijuana, the crosses hang off the border wall in Calexico, decorate San Diego’s Chicano Park, are staked into the ground in Holtville.

Each bears a different message: Clarity. Peace. Justice without borders. No Más. A remembrance of those who passed away. A reminder that they weren’t the first migrants killed this way. And that they will not be the last.

“Things have only gotten worse for the migrant community,” Hugo Castro, an immigration activist who helped to distribute and place the crosses, told my colleague Andrew J. Campa. “For the refugees and for those deported who give so much and get so little in return.”

There will be funerals and memorials to honor them. There will be hearings, and maybe even new laws, to address what happened and hope it doesn’t happen again.

Just like before. Of course, this will all happen at a time when open racism and racial polarization over issues like immigration have been catalyzed with renewed vigor by Trump — and the ghosts of hate he helped conjure up.

Either way, the bodies will get buried, here or thousands of miles away, and prayers will be offered and we’ll collectively move on.

California history sadly bears this out.

Monuments to the dead stand all over California. For those who gave their lives in war, who were lost at sea, or cut down by gang violence. There are three just for James Dean.

Next to none exist for Latino migrants. Those few that exist took decades to erect, usually long after survivors had passed and relatives only had faint memories of the departed.

It took 50 years to designate the stretch of the 101 where the Chualar accident happened as the Bracero Memorial Highway. It took over 60 years to replace a bronze plaque at Holy Cross Cemetery in Fresno that summed up what happened at Los Gatos with a breezy “28 Mexican citizens who died in an airplane accident” with a gravestone that listed all the victims by name. There’s still nothing permanent to mark the Blythe drownings.

There is little political will or public appetite to immortalize these martyrs of the California Dream. If we do, then we acknowledge that the system that brought them in and exploited them and ultimately killed them for the benefit of us all just might be broken.

And who wants to do that?

For over a decade, Ignacio Ornelas Rodriguez and other activists in Northern California have tried to raise funds to place a statue at the railroad crossing where the Chualar disaster happened. Right now, all that stands is a large wooden cross with small American and Mexican flags that reads “R.I.P. Los 32 Braceros.”

The Holtville crash shook Ornelas, not just in a historical sense but because he could relate: he entered the United States sitting in the middle of someone’s legs, with three uncles in the trunk of a car.

“We need to put the faces and names in front of the public to investigate and tell the world that these people matter,” said Ornelas, an archivist at Stanford. “Future generations need to know who were they. It needs to turn into a public history instead of being at some library at a college.”

Tim Z. Hernandez feels the same. In 2013, he and others pushed for the Diocese of Fresno to replace the generic marker to the Los Gatos dead with something that named everyone. The author went on to write a book and work on a documentary about that journey.

His motivation also came from personal experience. Growing up in the Central Valley, he recalls seeing descanzos — private shrines maintained at the sites of deadly accidents — all over America’s breadbasket. One of them marked the spot where his grandfather was involved in a crash that broke his back and left others injured and dead.

“We need to see something happen again and again before we ask ourselves, ‘Why does it happen, and how?’” said Hernandez, a University of Texas, El Paso professor. “That’s the saddest part right there. It’s become normalized that we’re seeing [such deaths] over and over, and that desensitizes us that these are human lives. By doing a memorial, it forces us to be accountable.”

He understands why it might take time to create a monument in the wake of what happened at Holtville and other such calamities. “It’s too painful a chapter for us to return to too quick,” Hernandez said. “We have to go through the phases of grief.”

But both he and Ornelas hope one goes up sooner rather than later.

“We have the power to do that now,” Ornelas said. “We can call [U.S. Senator Alex] Padilla and over 30 Latino Assembly members right now and do something about it. They have the money and the budget to make something happen in a matter of weeks — not months, not years. Now, there’s no excuse.”

A monument to the Holtville dead, to all our migrant dead, is the right thing to do — not only to commemorate their lives, but to confront the living. The Imperial Valley’s unforgiving sun and elements are already bleaching and chipping away at those crosses put up with such love and care.

Let’s do better than the uncaring society Guthrie decried in his long-ago ballad.

“Who are these dear friends who are falling like dry leaves?” his song asked. “Radio said, ‘They are just deportees.’”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.