How to be an ally: What you can do as a bystander to race-based harassment or violence

- Share via

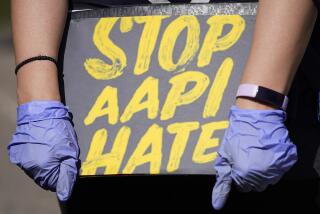

As coronavirus cases began to climb in the spring of 2020, so did incidents of anti-Asian harassment and violence.

Anti-Asian hate speech and a permissive attitude toward prejudice came from the top, with the then-president of the United States talking about the “China virus” and the “kung flu.”

On Tuesday, a white man killed eight people, including six Asian women, at three different spas in Atlanta. The victim’s names are Xiaojie Tan, Delaina Ashley Yaun, Paul Andre Michels, Soon Chung Park, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Yong Ae Yue and Daoyou Feng.

The killings rocked the Asian American community, already on edge after the wave of race-based violence during the pandemic. Just this week in San Francisco, a 70-year-old Asian woman fought off an attacker by herself.

Issues with data collection and poor rates of reporting make it impossible to accurately capture the number of anti-Asian hate crimes in this country. But some groups are working to shed light on how that hatred manifests.

In a new report, the group Stop Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Hate detailed 3,795 incidents of anti-Asian harassment and violence. Of the incidences, reported from March 19, 2020, to Feb. 28, 2021, 68.1% were verbal harassment; 20.1% were avoidance or shunning; 11.1% were physical assaults; and 6.8% were online harassment. Women reported incidents 2.3 times as often as men. In addition, 7.2% of victims said they were coughed or spat on. Stop AAPI Hate has a list of safety tips available in multiple languages for people who may be the victims of harassment.

Here’s what we know about the victims in the attacks on three Atlanta-area spas that left eight people dead, including six women of Asian descent.

If you witness someone saying or doing something racist, what can you do to safely intervene and help the victim? Several organizations offer guides and workshops for bystander intervention.

Here’s how to be an effective bystander and a good ally.

Practice the 5 Ds

The most important thing to know about intervening as a bystander is that your job is to create a safe atmosphere for the targeted person, not to confront the attacker. You aren’t Batman stepping in to fight the bad guys. You’re a human, being a friend to someone who needs it.

“You don’t have to be a superhero or make some huge superhero gesture to intervene,” said Jorge Arteaga, the deputy director of Hollaback, an organization that provides workshops, training and education materials to help end harassment. (Hollaback just added additional free virtual workshops on bystander training.)

In fact, confronting the perpetrator is likely to backfire, said Courtney Mangus, a programs manager for CAIR California, a civil rights advocacy group that offers workshops on bystander intervention. A person who’s already coming from a place of aggression will likely continue to escalate the situation if you get involved. So ignore them. She said you want to create a safe space for the target and give them an option to leave the situation. You aren’t their savior swooping in to rescue them. You’re a fellow human being acting from a place of kindness and support.

So what does that look like? Let’s say you’re on a public hiking trail and you hear someone shout a slur, or you’re on a train and you see someone loudly saying racist things in the earshot of a person of that race. Hollaback has a list of what it calls the “5 Ds” that constitute your options.

Distract. This is often the most helpful and effective thing you can do. The goal here is to interrupt the incident and indirectly derail the attacker. One method is by making conversation. Approach the targeted person and start talking about something unrelated. “Do you know if this trail goes up past the Hollywood sign?” “Does this train stop at Union Station?”

Keep the perpetrator in your peripheral vision, but focus on being physically present with the affected person. Help them find an exit: “Do you want to get off at the next stop with me?” “Want to walk over there with me and check out the view?”

“Be with them just like a friend would be,” Mangus said.

You can also create a small distraction: Spill your water bottle, or drop something on the ground. Disrupt what’s happening and draw focus away from the targeted person. Even just physically placing yourself between the perpetrator and the victim can serve as enough of a buffer to throw them off.

If you see someone being mistreated by a store employee, such as by refusing them service or making racist comments, ask the targeted person how you can help, said Manjusha Kulkarni, the executive director of the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council and the co-founder of Stop AAPI Hate. Introduce yourself and ask what you can do or what they need (find the manager? Walk them out of the store and to their car?) and take it from there.

“It is really about centering that person,” Kulkarni said.

Delegate. Find a person in a position of authority — the store manager, a transit employee — to let them know what’s going on and ask them to intervene. Or find someone in the immediate vicinity who may be better able to intervene than you.

Document. If you don’t feel safe intervening, you can help by documenting the incident. In California, you have the legal right to take photos and video when you are in public. The attacker might escalate the situation if they realize they’re being photographed, so try to do this in an unobtrusive way.

Delay. You might not feel safe intervening until after the attacker has moved on. Once that happens, you can still help by checking in with the victim.

It might not seem like an “intervention” at all since you aren’t acting in the moment, Arteaga said, but he said his group’s research indicates that even a knowing glance from another person after an incident can reduce the trauma for the victim. Express solidarity and let them know that what happened wasn’t OK, and that you want to check in.

“I’m so sorry that happened to you.”

“Can I call someone for you?”

“Can I walk with you somewhere?”

Direct. Only do this if you feel safe and comfortable speaking up. This is the riskiest response, because you can’t know how the perpetrator will react.

Avoid direct confrontation if the attacker has already been violent, Mangus said: “If someone has made physical contact, they’re already showing that they’re escalated enough, that they don’t see that there’s a boundary between your body.”

If you do feel safe, say something like, “Leave them alone,” or “That’s inappropriate/racist/disrespectful/not OK.” Keep it short and don’t engage in a discussion or argument. Then pivot back to helping the victim.

Pepper spray, Instagram and video: How Asian Americans in Southern California are dealing with anxiety about racial attacks during the pandemic.

What about calling the police?

Everyone interviewed for this article cautioned against defaulting to calling the police as your first response to witnessing harassment.

In most cases, Mangus said, the police officer who shows up will be the only person with a firearm. That instantly escalates the situation. And in the United States, there is a documented history of police harming the person they were called to help, particularly if that person is Black.

If the attacker has a firearm, Mangus said, that’s a good indication that you should call the police. But otherwise, try to resolve the situation without getting police involved.

There are other ways to seek government-based accountability and redress without calling the police, Kulkarni said. LA vs Hate is a community-based campaign that lets people report hateful incidents to 211, which is not affiliated with law enforcement. It does not have to rise to the level of a hate crime to merit reporting, Kulkarni said.

“Hate crimes are a very small minority of what Asians are experiencing right now,” she said. “We can’t police our way out of this problem; we can’t prosecute our way out of this problem.”

How to be a good ally right now

There are ways to be a good ally proactively. Posting a “Stop Asian Hate” graphic to Instagram is nice, but only if it’s the start of your activism. Kulkarni compared it to putting up a “Love Not Hate” sign in your yard. It’s a good way to indicate that you’re an ally, but you have to back it up with action.

Stop AAPI Hate has a list of ways to get involved and act right now. Here are a few ideas to get you started.

Hold your people accountable. If someone on your Facebook feed posts something about the “China virus,” call them out on it, either publicly or in a private message. Let them know that if they say something like that, they’re going to get pushback. It’s probably not going to be productive to engage with anonymous trolls online, Kulkarni said, but if it’s someone you know personally, there’s a chance of getting through to them. Or, at the very least, letting them know that people aren’t OK with what they’re saying.

Educate yourself. America has an ugly history of anti-Asian racism and violence. Read books and articles to become more knowledgeable about our country’s history. Lean more on what legal protections people have to be treated fairly in businesses. And educate yourself on ways to help, like signing up for one of Hollaback’s virtual bystander intervention trainings.

Get civically engaged. Kulkarni mentioned the number of people who publicly spoke at City Council and Police Commission meetings last summer during the Black Lives Matter movement. All those meetings are still taking place over Zoom, which means it’s easier than ever to weigh in and demand accountability and action.

Support local businesses owned by Asian people. Since the start of the pandemic, many Asian-owned businesses have suffered from racist backlash. Show them your support by being a customer.

Donate to anti-hate and civil rights organizations. Contribute to groups pushing back against hate. In other words: Put your money where your posts are.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.