Column: L.A. should take a lesson from Sacramento on how to clear a homeless encampment

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — To look at the grim sidewalks that stretch under Highway 50 at the south end of midtown Sacramento, it’s hard to understand why anyone — no matter how desperate — would want to call these blocks home.

It’s always dark. It’s dirty. It stinks. And there’s an incessant rumble of cars and trucks, punctuated by the occasional blaring of a horn and screeching of brakes.

But for Shane, a homeless man I found absent-mindedly drawing on a piece of paper inside his tent on Monday afternoon, the underpass and the nearly 300 people who lived there with him for months had come to feel familiar.

The only reason he agreed to move a few blocks away to a new, city-sanctioned camping site for homeless people, known as a “safe ground,” is that others from the encampment were going, too.

“They told me we could come over here,” Shane mumbled, under the protective gaze of two friends. “So here I am.”

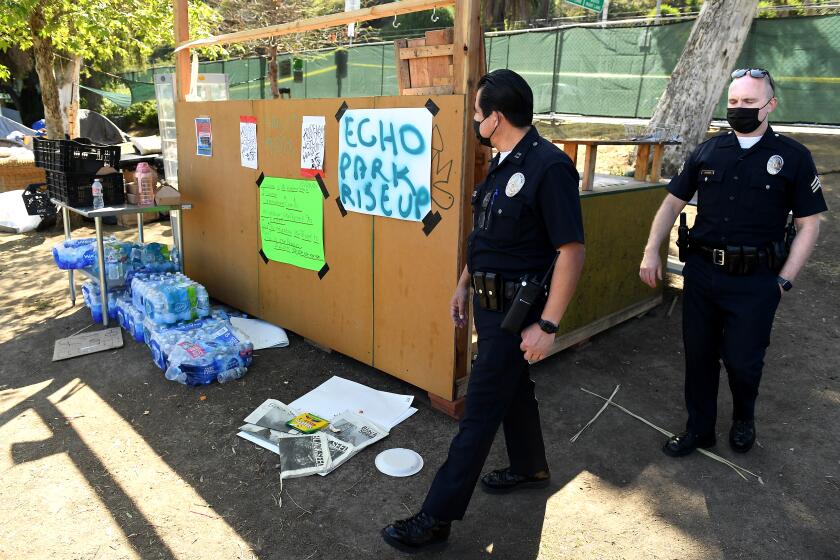

I can’t help but feel there is a lesson in here for Los Angeles, where city officials are still getting grief from some of the homeless people who were forced out of their commune-like encampment in Echo Park and dispersed to temporary housing all over the county.

As I wrote last week, some of those former park dwellers have found being split up so dispiriting that they’re thinking about abandoning their four- and five-star hotel rooms — provided under the government-funded program Project Roomkey — and returning to the squalor of streets. Others, fearful of losing track of everyone in the community they had built on the banks of Echo Park Lake, never went to a hotel at all.

L.A.’s elected officials see the shutdown of an Echo Park encampment as a success. The homeless people who ended up in hotels don’t agree.

While their distress is likely to garner little sympathy from housed Angelenos who are rapidly losing patience with mushrooming encampments, it does raise important questions about the effectiveness of L.A.’s strategy on homelessness if people won’t take the help that’s offered.

Which brings me back to Sacramento.

Faced with a similar need to clear a massive homeless encampment on short notice — in this case, so Caltrans could start widening Highway 50 — officials here chose a different strategy than L.A. did and found a way to keep as many people as possible together.

Sacramento City Councilmember Katie Valenzuela moved quickly to hammer out a deal with Caltrans to use a parking lot alongside Highway 50 for the safe ground.

The city then tapped outreach workers to spread the word that all those at the encampment had to do was pack up and move less than a mile down the street. Those who did so would have access to bathrooms, food, services, storage and, most important, could continue to come and go as they please.

“We’re trying to help people get off the streets, but also remain part of a community, even while they’re living outdoors,” explained Mayor Darrell Steinberg, who also is co-chair of the state’s homelessness task force.

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“It’s really important that we honor that,” said Valenzuela, whose background is in community organizing. “These are the only folks that they feel safe around, that they’ve established a routine with, and so we didn’t want to break that up. And also, just from a practical aspect, they’ve formed sort of natural COVID pods.”

So far, the results have been encouraging.

In the short time that the safe ground has been open, at least 85 people have moved in, pitching tents and parking their vehicles and RVs. More are arriving every day, and city officials expect that will ramp up as word gets out and homeless people begin to trust the city’s intentions.

What would’ve happened if caseworkers in Los Angeles had been able to move everyone camping on the banks of Echo Park Lake to another site en masse — be it a Project Roomkey hotel or a parking lot?

I have to think more people would’ve agreed to go and wouldn’t have as many qualms about staying. That’s because homeless people don’t just want housing; they want homes. They want community — just like we all do.

“It always astounds me why people think that people, once they become homeless, they’re not like us anymore,” said Bob Erlenbusch, executive director of the Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness. “They build up friendships and watch each others’ stuff while they leave. All the stuff that goes with community protection.”

Granted, relocating an encampment without losing any members of it requires time and it requires patience. And many housed residents in California are understandably fresh out of both.

Homelessness seems to have grown exponentially worse during the COVID-19 pandemic — not only because the devastated economy pushed more people onto the streets, but also because, until recently, encampments have largely been left alone, with outreach workers abiding by public health guidance to do so.

At a time of intense frustration around homelessness, Gabriel Donnay’s killing by an intruder who police say was living in his car has family, friends and neighbors saying change must come.

Meanwhile, in Beverly Grove, residents have had it after the killing of 31-year-old Gabriel Donnay, who was apparently stabbed in his own backyard by an intruder who police said was living in his car.

And after the clearing of the encampment in Echo Park, residents are demanding the same along Ocean Front Walk in Venice, pointing to rampant drug use and a series of destructive fires that have charred several buildings.

In response, L.A. City Councilmember Mike Bonin has floated the idea of opening Sacramento-style safe ground sites in Pacific Palisades, Marina del Rey, Playa del Rey, Venice, Del Rey and Westchester. Of course, there’s already an online petition against any “legalized homeless encampment at Palisades Beach.” As of Tuesday afternoon, more than 7,000 people had signed it.

Even in Sacramento, residents have taken to social media to criticize the new safe ground alongside Highway 50 and the plan to open at least a half-dozen more spaces for city-sanctioned, staffed encampments in different neighborhoods.

“I’ve taken flak for either not doing nearly enough or doing way too much,” as in “all you’re doing is making the city a magnet” for homeless people, Steinberg said.

This is why he sees safe ground as the first part of a “master plan” that could have statewide ramifications — that is assuming he can convince the Legislature to make it easier to open shelters and other facilities for homeless people without the fear of lawsuits from NIMBY residents.

It’s a long shot. But what’s happening now clearly isn’t a sustainable strategy for getting people off the streets permanently in a post-COVID world.

Perhaps it’s time that we stop looking at a solving homelessness through the narrow lens of just getting a roof over somebody’s head and start looking at it through the broader mission of building and maintaining communities.

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.