California encourages venues to require vaccine ‘passports’ — just don’t call them that

- Share via

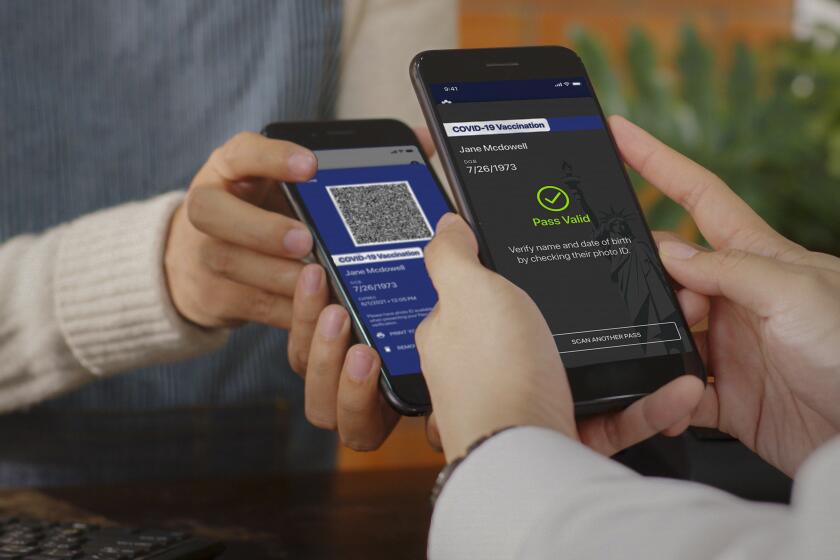

California health officials have repeatedly said they have no plans to institute COVID-19 vaccine “passports” — digital or paper passes that allow vaccinated residents or those who’ve tested negative into concerts, baseball games and other sports arenas.

But this month, the state announced reopening rules for indoor live events that give businesses an incentive to demand such proof from ticket holders. Businesses can hold larger events when they verify either of the safeguards.

“Of course, it is a form of a vaccine passport,” said Dr. John Swartzberg, a UC Berkeley infectious-disease expert.

That California has not embraced the label is unsurprising, he said.

“What is happening to vaccine passports is the same thing that happened with masks,” Swartzberg said. “It has become politicized, and that is really just unfortunate.”

As the pandemic continues, vaccination requirements by California employers, colleges and others will probably grow, particularly once the vaccines can be easily obtained and win formal federal government approval. Private companies and medical and education institutions are already working to produce a pass, akin to an airline boarding pass, that could be used digitally or printed out.

We explain what vaccine passports are, how they work, where they’ve been implemented, and why some people object to them.

“The idea of vaccine verification is very old,” said Dr. Christopher A. Longhurst, a professor of pediatrics and chief information officer for UC San Diego Health.

Scores of countries require that travelers carry “yellow cards” verifying inoculation against yellow fever or other diseases. In the United States, children have long been required to be vaccinated to attend schools and camps.

“What is new and different and what is scaring some people is the idea of vaccine verification not for employment or school registration but for daily activities,” Longhurst said. “You need to show it more frequently.”

UCLA constitutional law professor Eugene Volokh said a vaccine pass might have generated less opposition if it hadn’t been dubbed a passport, which is a government-issued document and “makes it sound like the government is controlling your movement.”

“Communicable disease creates a special imperative that authorizes things that otherwise people might be skeptical about,” said Volokh, one of many legal scholars who says such passes are constitutional. Still, he said, it was not surprising that verification systems might worry some.

“It’s just not an American thing to be constantly told, ‘Your papers, please,’” he said.

Longhurst and UC San Diego are working with a group called the Vaccination Credential Initiative, which is helping develop a system that aims to produce trustworthy and verifiable copies of COVID-19 vaccination records in digital or paper form.

Whether such passes become widely used will depend in part on public health as well as political leanings. In places where most people are vaccinated and the virus levels are low, it might not make sense, Longhurst said.

“This will really be driven by the market,” he said. The U.S. government “is not going to mandate vaccine passports. This is very clear. But other governments will require it, most certainly,” particularly for international travel, he said. Israel already has a robust vaccine passport system.

In the U.S., he said, it will take at least two to three more months before a workable, technical standard is developed for health passes.

Dr. Robert Wachter, a professor and chair of the UC San Francisco Department of Medicine, said he anticipated that proof of vaccination would eventually be required to travel or attend certain events.

“If you thought masks were a hot potato,” he said, “wait for this one.”

Wachter has been fully vaccinated but still won’t dine indoors at a restaurant because the vaccines aren’t foolproof. If a restaurant ensured all its employees and patrons were vaccinated, Wachter said, he “absolutely” would partake.

Swartzberg said he would pay a premium to fly on an airline that required travelers to show they were vaccinated against COVID-19.

“If I knew a store that said people who come in here have to be vaccinated, I would preferentially go to that store,” Swartzberg said.

The 2011 movie “Contagion” presciently displayed vaccine passports, said Longhurst, who also serves as associate chief medical officer for quality and safety at UC San Diego Health. The movie is about a deadly virus that spreads around the globe. Scenes show Americans having to wear wristbands proving vaccination to enter stores.

In real life, the United States has had vaccine verification campaigns to curb smallpox outbreaks. At the turn of the 20th century, proof of vaccinations was required in some places to go to work and school, ride trains and even attend theaters. Health officials often demanded to see a vaccination scar rather than rely on certifications that could be forged.

Some cities created virus squads, going door to door to check people’s vaccination status, said Michael Willrich, a history professor at Brandeis University. People who refused to get a vaccine resorted to exposing part of their skin to nitric acid. It created a nickel-sized scar similar to the mark left by the vaccine.

In 1905, the Supreme Court upheld state laws that require vaccination for communicable diseases. In a 7-2 decision, Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote that “the rights of the individual … may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.”

Legal scholars say states have the latitude to either require vaccine passports or ban them in their jurisdictions, and the political fighting has already begun. Conservative governors in Texas and Florida have banned them, arguing that vaccination cards are personal medical records that shouldn’t have to be revealed. Liberal New York has authorized an “Excelsior Pass” to prove vaccination or a negative test result for entry to Madison Square Garden, large weddings and live performances.

In California, Assemblyman Kevin Kiley (R-Rocklin) has drafted a bill to ban such passes “as a condition of receiving any service or entering any place.” The legislation is unlikely to go far in the state Assembly and Senate, both controlled by Democrats.

Dr. Mark Ghaly, the state’s health and human services secretary, said he did not view California’s rules for reopening indoor venues as a vaccine passport. A pass system would have to be carefully designed to protect privacy and ensure fairness, he said.

“We’re working through whether it makes sense in the highest-risk venues — large, indoor, random-mixing environments — where there could be an expectation to have vaccine or testing verification,” Ghaly said in an interview.

The new state rules vary according to a county’s place on the state’s color-coded risk tier. In the orange tier, in which virus spread is moderate, the capacity for indoor venues will be capped at 15% or 200 people. But if the operator demands proof of vaccination or a negative test, the venue can more than double capacity to 35%.

Under the rules, theaters, music halls and other indoor venues will have to decide whether opening at limited capacity makes financial sense and whether they want to risk blowback from customers who object to verification of vaccinations or tests. That may not be an issue in urban areas that support vaccinations but could pose quandaries for businesses in “redder” parts of the state, where opposition to vaccine passports runs high and relatively fewer people have been inoculated.

The U.S. government won’t issue so-called vaccine passports, the White House said, after Texas sought to limit their development due to privacy concerns.

Several universities around the nation plan to require students to be vaccinated to return to campus in the fall. The University of California system, which last year required all students and staff to receive a flu vaccine, has yet to decide whether to mandate a COVID-19 inoculation.

The California State University system will not require vaccines, at least not until they get formal approval by the Food and Drug Administration, though some campuses may require athletes and dormitory residents to get the shot, spokesperson Mike Uhlenkamp said.

San Francisco, which has conservatively managed the pandemic, allowed fans to attend Giants games this month after the team agreed to require people 12 and older to present either proof of vaccination or a negative coronavirus test. About 7,300 fans attended the home opening game at Oracle Park, close to the roughly 8,000 allowed by health officials.

Julie Elliott, 46, a teacher and ardent Giants fan, lauded the safety protocol. “It is respectful of the other fans and the players and their families,” she said.

Elliott has been vaccinated, but her 14-year-old daughter is not yet eligible and would have to be tested to enter the venue. “It wouldn’t stop me from taking her to a game,” Elliott said.

The Golden State Warriors, following San Francisco rules, also will ask attendees to show proof of a negative test or a vaccine to enter their stadiums.

“We know that much of what makes San Francisco special are the live performances and events where people can come together for music, sports and cultural performances and graduations,” Mayor London Breed said in a statement. “We are excited for this step and what lies ahead, but we all need to keep doing our part to put safety first.”

Times staff writer Luke Money contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.