When needles strike fear, practice comes before the COVID-19 vaccine

- Share via

Margie Garcia, the mother of an 18-year-old with autism, desperately wants her son to receive the COVID-19 vaccine.

But she fears that the sight of the syringe could trigger his anxiety, causing him to run away or tackle someone.

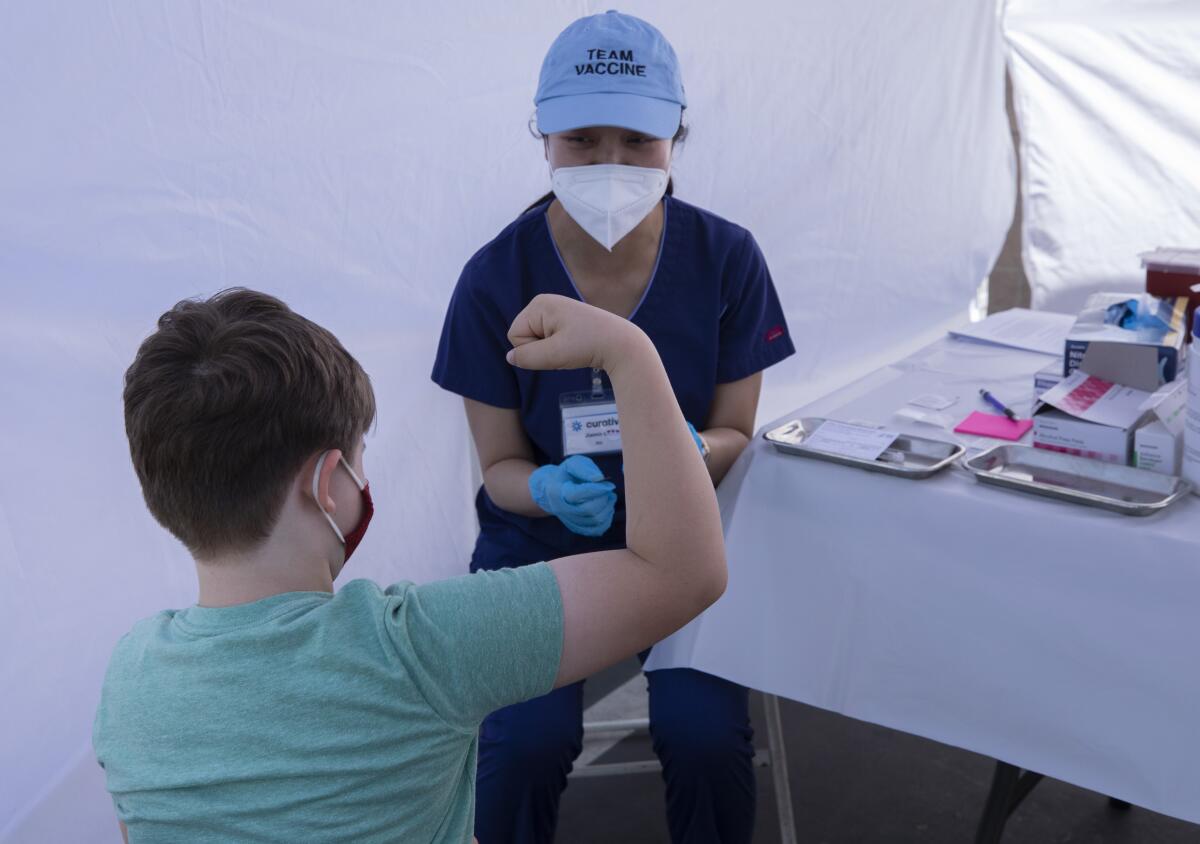

So last week, her son, Niko, made a practice run at a mock clinic along with dozens of other young adults and children with developmental disabilities. He went through a registration process, then a nurse placed a syringe — needle-less — against his arm and stamped the spot with a bandage. Afterward, he sat in an observation area, wearing red headphones to block out any unexpected noise. All around him in the parking lot floated bubbles and balloons.

The goal of the clinic was to create a controlled environment free of stimuli that could cause distress, and it worked for her son, said Garcia, 47.

“It’s so difficult to go to a non-special needs population vaccination climate,” said Garcia, who worried about her son being overwhelmed by unexpected noise or bright lights. “This is really, really beneficial for him.”

For most children and young adults with developmental disabilities, the vaccination process takes place without incident. The scene at the mock clinic held by the Friendship Foundation — a nonprofit in Redondo Beach — was mostly calm, and aside from a few grimaces and some coaxing, most participants went through the simulation with ease.

But reactions to a new environment can be unpredictable, raising concerns for parents and advocates. Some are cautious about exposing their children to situations that could cause them to panic and physically resist. People with autism do not always respond to the commands of a stranger. The mock clinic itself was inspired after a parent shared a story of her son having to be held down to receive the shot.

A standard vaccine clinic, advocates say, isn’t always a conducive place for some people with disabilities to get a shot: Appointment slots are rigid, time to get comfortable within a new environment is limited, waiting areas overwhelm. The experience can be anxiety-inducing for anyone. For those who may not comprehend what the process entails, it can be debilitating.

In an attempt to facilitate the vaccination process at home, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department unveiled an initiative this year called Operation Homebound, which sends teams of health workers and police to vaccinate senior citizens and people with disabilities in their homes.

But the program, which uses the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, was put on hold following a pause in the vaccine’s distribution.

Vaccine shots at home would be the preference for those with disabilities who fear needles or who have difficulty controlling their bodies, Disability Voices United President Judy Mark said.

“With that option off the table for now, it is critical that these individuals get practice and feel prepared before getting the shot to reduce their fear and discomfort,” she said. “We have to figure out a way to deliver healthcare, to deliver services to people with developmental disabilities that work for us — not work for the system.”

The mock clinic — a collaboration between Disability Voices United and the Friendship Foundation in partnership with vaccine provider Curative Inc. — offered walk-in and drive-thru options. Curative was slated to come back in a few weeks to the same spot to deliver a single-shot Johnson & Johnson dose — though it’s unclear now when that might be.

“They’re going to see physicians today, they’re going to see medical staff. It’s going to give them practice to ease their minds,” said Nina Patel, the managing director for the Friendship Foundation. The space was one that was well-known, and many of the helpers were familiar faces — trust had already been established.

The goal of the mock clinic, though developed with vaccine recipients in mind, was twofold — the patients could get comfortable with the idea of a shot in a safe space, and the families could offer feedback to staff about what to do — and what not to do.

Do offer praise.

Do provide distractions.

Don’t ask overly complicated questions.

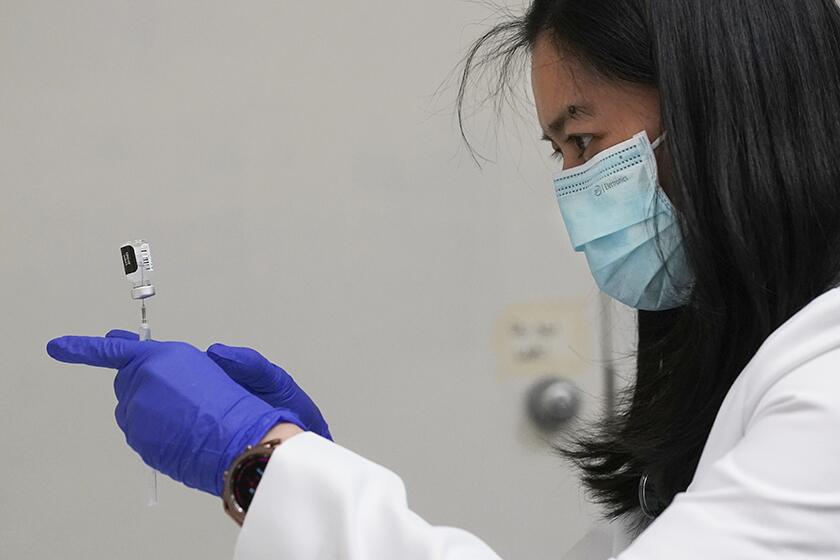

“Try to keep it simple,” nurse Jiamin Lin, 30, said. Lin, who has worked with Curative to administer the vaccine, said a big tip she received was to hold up two fingers for a patient to point at when answering “yes” or “no.” Lessons like that, as well as video and photos of the event, would be shared with Curative staff and others within the disability community.

Many of the families who showed up for the mock clinic had children who aren’t yet eligible for the vaccine but will be in the months to come. For them, the early practice was welcome.

Carrie Wetsch, 48, said that her 14-year-old son, Tyler, doesn’t do well with needles. And the pandemic has limited her boy’s social interactions. The ability to pretend to get a shot from the comfort of the car was an experience that will benefit Tyler in the long run.

“That positive memory for him, I think, will make a huge difference. That can make or break an important medical situation,” she said.

Brandon Velasquez, 39, felt similarly. He had prepared his teenage son throughout the week for the experience. He was nervous, and can’t always communicate his feelings, his dad said. But he made it to the final step, accompanied by his dad and his puppy, Kobe.

“I’m feeling good,” the boy said inside the waiting area.

For someone like Niko Garcia, a teenager with autism, the ability to get the shot in a familiar space is essential. To reduce risk of misunderstandings with authorities, Niko’s mom has registered him with the local Sheriff’s Department in Carson as a special needs child.

“He has a disability and he’s Asian. In today’s time, Niko is doubly discriminated against,” his mom, Margie Garcia, said.

When the 15 minutes were up, participants high-fived staffers and took home goodie bags filled with balloons, candies and stickers.

Mission accomplished — the real shot would come soon.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.