Column: What a fight over a noose says about the coming clash of red and blue California

- Share via

Mike Saunders thought the fight was over.

For almost a year, he’d made it his mission to persuade the city of Placerville — perched in the remote Sierra foothills, not far from Lake Tahoe — to change its official logo from a noose swinging from a tree.

For the record:

9:57 a.m. May 5, 2021An earlier version of this story said the town of Truckee was in Placer County. It’s in Nevada County.

The noose, he’d explained again and again with uncanny patience, is a symbol of hate and violence toward people of color. In Placerville, or as the locals call it, “Old Hangtown,” let’s just say the majority of those who were hanged during the vigilante justice era of the Gold Rush weren’t white.

And yet, many in this overwhelmingly white and conservative city resisted, arguing that the noose was merely a cultural and historical symbol, and had nothing to do with racism. Meanwhile, Saunders, who is Black and liberal, was hit with a barrage of racist taunts and threats.

When I interviewed him last summer, Saunders expected that his campaign against the noose would succeed — eventually. And in mid-April, he was proved right when the Placerville City Council voted unanimously to change the logo.

“Noose down!” he texted me at the time.

What Saunders didn’t expect was that, two weeks later, the same City Council would vote unanimously for a resolution to allow the city’s nickname, “Old Hangtown,” to continue to be used on signs, like the massive one that greets drivers along Highway 50.

The fight to retire Placerville’s noose should serve as a warning, in this time of support for Black Lives Matter, that change will not happen quickly.

Mayor Dennis Thomas said the resolution was necessary to head off a “slippery slope that it’s part of this whole grand scheme of taking down everything historical in the city.”

Then again, this is Placerville, where a mannequin that many locals affectionately call “George” still hangs from a noose on the side of a downtown building.

The sequence of events has left Saunders trying to make sense of it all.

Beyond the obvious racism involved in celebrating extrajudicial hangings, he has come to believe what happened is also a reflection of a deep-seated — if irrational — fear that has taken root in Placerville and in other pockets of red California that they are about to be taken over by blue California.

It’s a fear, this paranoia over a supposed invasion of liberals, that has only grown during the pandemic as remote work has become more prevalent and some have moved inland to escape increasingly high housing costs in coastal cities or settle in to a new way of life in rural resort cities.

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Take the town of Truckee, for example. Located a couple of hours from Placerville, just north of Lake Tahoe, it has recorded a larger percentage of new residents from San Francisco than any other U.S. city during the pandemic, as my colleague Liam Dillon reported last week, citing an analysis of U.S. Postal Service data by the San Francisco Chronicle.

“They want to hold on to these values and ideals,” explained Saunders, who has lived in El Dorado County, home to Placerville, for almost 20 years. “It’s, you know, ‘I don’t want to give up being the red part of the state’ and the noose plays into that.”

::

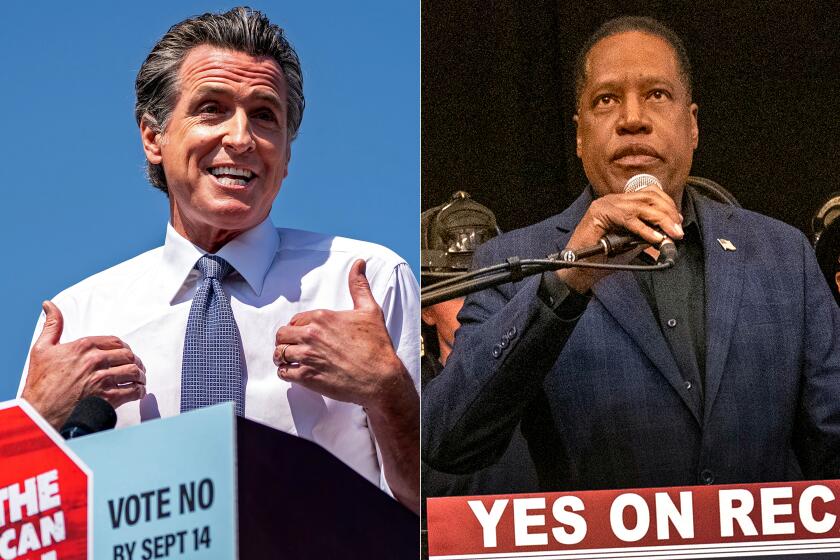

As the circus-like campaign to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom gets underway in earnest, there’s one narrative that you’re likely to hear repeatedly between now and the election.

In fact, it took only a couple of hours after the U.S. Census Bureau released population data last week, confirming that California will soon lose a congressional seat, for former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer, a Republican challenger, to tweet it.

“Gavin Newsom’s policies have been an assault on affordability and livability for families across this state,” he posted in a statement that also made the rounds in a campaign email. “Californians are being forced to leave their home state in droves.”

The truth is, of course, more complicated than that.

There is no mass exodus from California. Yes, people are leaving and fewer people are arriving from other states. But other factors, including fewer babies being born, have also contributed mightily to the state’s slowing population growth. Multiple studies have shown that.

But multiple studies also have shown there is a very real “assault on affordability and livability” that is driving Californians — especially working-class Californians — out of more expensive, mostly liberal, urban coastal areas and into less expensive, mostly conservative, rural inland areas.

The number of people moving is relatively small, but it is noticeable. Think Los Angeles to the Coachella Valley. Or San Francisco to Placer and Nevada counties, the latter of which is home to Truckee.

Vacation destinations have become primary homes during the COVID-19 pandemic as Lake Tahoe and Palm Springs see surges in population and housing costs.

Many of these rural counties, particularly in Northern California, have long felt underrepresented, ignored and steamrolled by the state’s Democratic majority. So it’s no surprise that, according to a recent Times data analysis of the roughly 1.6 million valid signatures gathered to oust Newsom, the highest concentrations were collected from voters in conservative counties to the north and east of Sacramento. That includes El Dorado County.

Saunders sees this support for the recall as part of the broader backlash to the exaggerated belief that rural counties are being invaded by liberals.

During the months of debates over the noose, for example, one of the main talking points from opponents was that “people from the Bay Area” were behind the push to change the logo — an unfounded claim. Even Saunders, who has lived in El Dorado County for almost 20 years, said he has frequently been accused of being an outsider.

City Council members, two weeks after voting to lose the noose, said they were affirming that the Gold Rush-era name would stay.

And last week, during the City Council’s debate over the resolution to protect the “Old Hangtown” nickname, several callers alluded to outsiders bringing in “wokeism.”

“They’re coming after every business, every noose that’s around this town — they’re coming after everything,” one caller, Placerville resident Mandi Rodriguez, said. “This virus, critical racism wokeism, is going to destroy our country.”

It remains to be seen if housing prices and remote work will continue to encourage people to relocate away from the coast, but it’s more likely than not that the clash between red and blue California will continue. Placerville is just the latest battleground.

“I have to remind people, there are symbols of inclusivity and exclusivity,” Saunders said. “No one’s trying to change culture or anything, but there’s just norms of society now that you have to work with.”

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.