From homelessness to homicides, Garcetti leaves L.A. with unfinished business

- Share via

For Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, there is so much unfinished business.

Homeless encampments have taken hold throughout the city, even though hundreds of millions of dollars have gone toward shelter and low-income housing. Transit ridership has been declining for years, despite billions of dollars devoted to new rail construction.

And while city leaders are looking to rework the duties of the Los Angeles Police Department, moving away from armed responses to certain calls, they’re also contending with a surge in homicides and gun violence.

The person who succeeds Garcetti as mayor will have to confront those issues and decide whether to embrace the departing mayor’s current agenda or chart a different course.

Given public dissatisfaction with homelessness, crime and public transit in the city right now, it’s almost certain that several candidates who run for mayor in June 2022 will promise change, said political consultant Dermot Givens.

In the short term, any interim replacement for Garcetti will be less likely to rock the boat, Givens said. “To get appointed by the council, they would have to promise ... they’re not going to make waves, or create any interference for the upcoming campaign.”

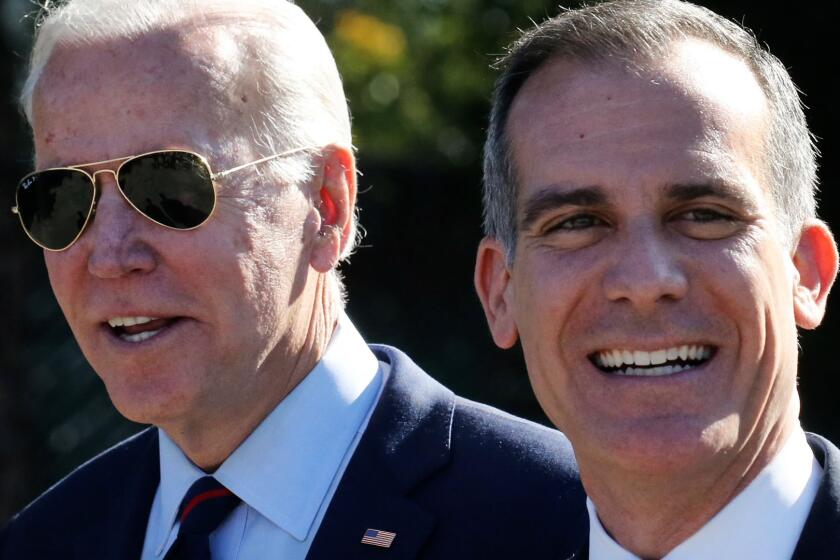

President Biden selected Eric Garcetti to become U.S. ambassador to India. Garcetti would step down as L.A. mayor after Senate confirmation.

President Biden announced Friday that he had tapped Garcetti to serve as the U.S. ambassador to India, a position that requires U.S. Senate confirmation. How much more Garcetti could have accomplished over the next 18 months, when his term is scheduled to end, is a subject of debate.

Garcetti allies say his biggest initiatives — expanding the county’s transit system, transitioning away from fossil fuels and building permanent housing for homeless Angelenos — were always going to take several years to execute, going well beyond his two terms in office. They also argue that key pieces of his agenda are already completed, such as increases to L.A.’s minimum wage and the recent renegotiation of city employee contracts, which significantly cut costs.

Whether Garcetti’s work is viewed as finished or unfinished, a new mayor could chart a sharply different course, replacing his department heads, choosing a different crop of volunteer city commissioners and pursuing different strategies for addressing the city’s biggest problems.

Garcetti’s replacement also could have a different take on the role of city government.

Although he spoke frequently during his tenure about taking City Hall “back to basics,” Garcetti pushed city agencies out of their comfort zone during the COVID-19 pandemic, assigning them duties that were not part of their core mission.

The Biden administration could nab L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti. If so, he will leave with a mixed legacy.

The mayor opened free COVID-19 testing sites, even though county government — not City Hall — is responsible for public health. He had librarians and other city employees serve as contact tracers. And he helped turn some of L.A.’s most recognizable spots, including Dodger Stadium, into major vaccination sites.

“It will be interesting to see whether an interim mayor will be as willing to draw outside the lines as Garcetti has been,” said sociology and American studies professor Manuel Pastor, who directs the Equity Research Institute at USC.

Addressing homelessness

As Los Angeles emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, its most pressing issue by far is homelessness. The humanitarian crisis has sparked public calls for action that are frequently in conflict, with some demanding the removal of tents from parks and sidewalks and others insisting that encampments remain until permanent housing is available for those who need it.

Garcetti pledged nearly $1 billion for homelessness initiatives in his budget, with Gov. Gavin Newsom calling for billions more statewide. That money could make this the most critical moment for homelessness in Los Angeles in nearly 40 years, said Gary Blasi, professor emeritus of law at UCLA.

Blasi fears that much of those funds could be spent on temporary measures to make homeless encampments less visible, while failing to address the root of the problem. “This is a time of tremendous potential that could easily be squandered chasing short-term political gain,” he said.

Over the past year, Garcetti has attended ribbon-cuttings for new shelters, “tiny home” projects and affordable housing built with funding from Proposition HHH, the $1.2-billion bond measure he endorsed in 2016. He also has been grappling with a federal judge’s recent order to get people off skid row, which is now on appeal.

Judge David O. Carter has chided Garcetti for concentrating HHH funds so heavily on permanent housing with social services, which has been expensive and slow to build. That criticism has cast “a pall of uncertainty” over the city’s strategy for combating the crisis, said Alan Greenlee, executive director of the Southern California Assn. of Nonprofit Housing, which represents developers of affordable housing.

“The debate is turning into this zero-sum game” between housing and immediate shelter, Greenlee said. “We have to do both.”

By August, city officials expect to have opened more than 6,400 beds for homeless people — motel rooms, overnight parking and other facilities — over a 14-month period. Meanwhile, housing advocates have begun strategizing about what happens when the city runs out of HHH money, which will only serve a fraction of the city’s homeless population.

One idea being discussed is a new voter-approved tax, said Tommy Newman, vice president at the United Way of Greater L.A. The next mayor will have to decide whether to support such a strategy, Newman said, and look for ways of building permanent homeless housing that are less expensive.

“It’s the right time to have a debate: Do we keep investing in affordable-housing creation the way we’ve been doing it? Or do we find new ways of reducing costs and building it faster?”

The future of public transit

Garcetti also has been facing questions about the future of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, where he served repeatedly as chairman and controls four of the board’s 13 seats. Metro is in the middle of a construction boom, building new rail lines in downtown Los Angeles, on the Westside and elsewhere, paid for in part by Measure M, the transportation tax Garcetti championed in 2016.

Yet Metro is also struggling with declining ridership. The agency saw weekday boardings on its buses and trains drop from 1.5 million in September 2013 — not long after Garcetti was sworn in as mayor — to 1.2 million in September 2019, according to Metro’s figures.

By September 2020, six months into the city’s COVID-19 shutdowns, weekday boardings had fallen again by half, below 600,000. Metro is now attempting to rebuild.

With passengers starting to return, the next mayor will need to figure out how much of L.A.’s workforce intends to work from home permanently, said Richard Katz, who spent eight years on Metro’s board. The answer, he said, could scramble passenger demand and complicate the effort to rebuild ridership.

“You’ve got to look at the impact on light rail,” he said. “You’ve got to look at the impact on long-distance commuting.”

Garcetti has championed efforts to provide free fares for children, college students and seniors, which could potentially boost ridership but also take a bite out of the agency’s budget. At the same time, transit activists are arguing that the entire Metro system should be free to all passengers.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Metro bus passengers have not had to pay. But that could change in the coming months.

Remaking the LAPD

While Metro is grappling with whether to go fare-free, the Los Angeles Police Department is facing far more urgent demands for change in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

Last year, Garcetti and the council responded to massive protests over Floyd’s killing by cutting the LAPD’s budget, reducing the size of the force and promising new measures to take some assignments out of the hands of police.

Garcetti has embraced a pilot program to send social workers, not police officers, to nonviolent mental health emergency calls. Meanwhile, city agencies are preparing to study strategies for moving traffic assignments out of the LAPD, possibly by handing them to civilian city workers, such as parking enforcement officers.

Taking traffic enforcement away from the LAPD would reduce the number of traffic stops that end in police violence, said Chauncee Smith, who manages the Race Counts initiative for the nonprofit civil rights group Advancement Project California. Such a move would also decrease the number of racial profiling incidents involving Black and Latino motorists, he said.

“Whether the mayor is Garcetti or some other person,” Smith said, “there is an urgent need ... to explore alternative models of traffic safety.”

But while grassroots activists have been urging city leaders to scale back the LAPD’s duties, others have been voicing alarm over rising gun violence.

As of July 3, homicides were up nearly 41% compared to the same period in 2019 — the last full year without COVID-19, according to LAPD statistics. The number of shooting victims was up nearly 40% over the same timeframe.

A plan for how to solve Venice’s homeless crisis has emerged from behind-the-scenes talks among a coalition of Venice activists, city officials and deputies of the area’s city councilman.

Jorja Leap, adjunct professor at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, said she fears the surge in gun violence could spark a public backlash against community policing programs and partnerships with gang intervention workers.

“What terrifies me is that people will say, ‘Crime is increasing, we’ve got to stop this,’” she said. “And they’ll go back to the bad old days of command-and-control policing.”

The next mayor, interim or otherwise, will face calls to rethink city spending priorities and invest more heavily in marginalized neighborhoods.

Shifting priorities

The city’s newest budget sets aside $35 million to keep Angelenos from slipping into homelessness and even more for a citywide guaranteed-income pilot program, which will aid families on the brink of poverty, according to the mayor. Those investments were largely made possible by a windfall of pandemic relief from the federal government, which runs out next year.

The next mayor will have to decide whether to keep those programs going and, if so, how to pay for them without that federal money, said Hamid Khan, coordinator for the Stop LAPD Spying Coalition.

Khan’s group has long called for big cuts to the LAPD, with the proceeds going toward housing, child care and other social services. “Exactly what are the priorities of the city?” he asked. “Does the city want to keep being a police state and police their way out of all these problems?”

Former City Councilman Mike Hernandez believes a shift in priorities is already underway, with the city’s elected leaders putting more money into aid to immigrants, working-class renters and those who are homeless. The mayor and council, he said, are confronting “the reality that we’re a majority-minority city.”

“We’re trying to basically create environments that are welcoming to everybody,” he said. “And it’s going to cost a lot of money.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.