Ed Buck is cast as deadly predator as overdose trial opens

- Share via

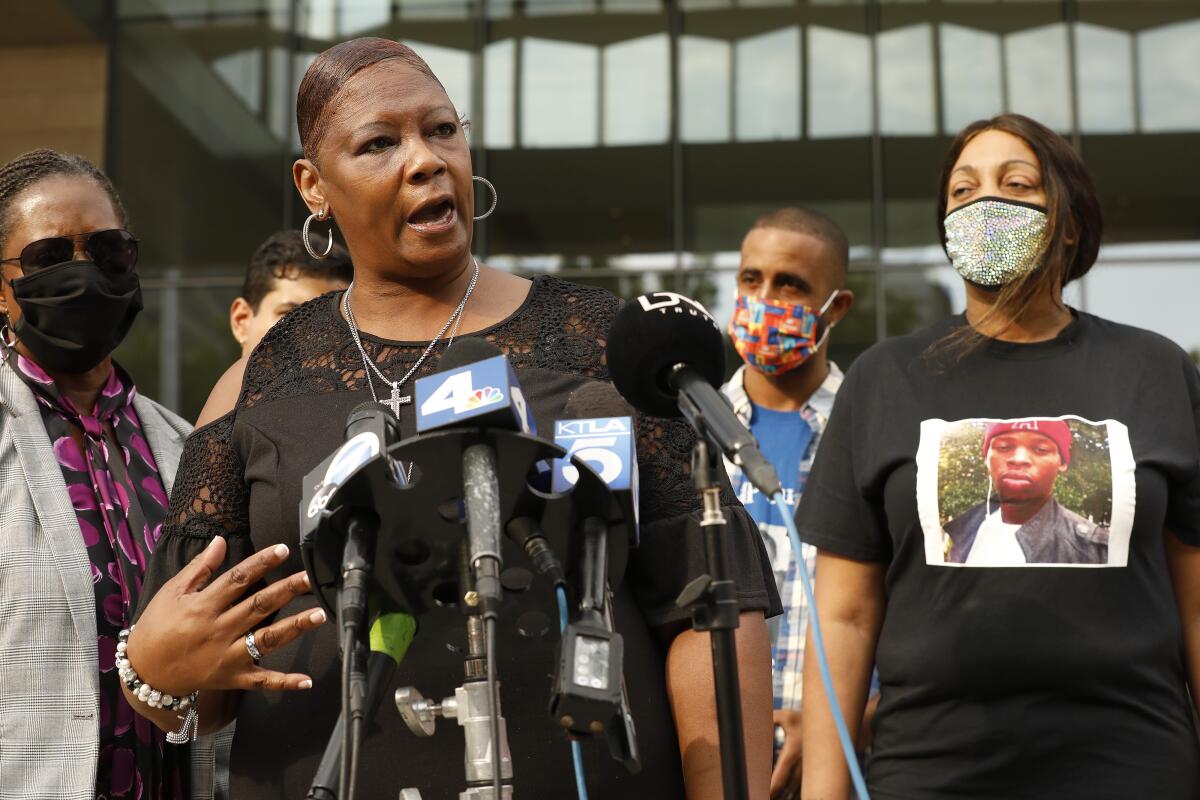

Joyce Jackson still struggles with the pain of losing her brother Timothy Dean to a fatal drug overdose in the West Hollywood apartment of Ed Buck.

So when Jackson arrived at a federal courthouse in Los Angeles on Tuesday, it was with a measure of hopefulness: Buck was going on trial on charges of supplying the methamphetamine that killed her 55-year-old brother in 2019 and another man, Gemmel Moore, 26, in 2017.

“It’s a somber day, but it’s still a good day because we are here to make sure that my brother gets justice,” said Jackson, who with her sister Joann Campbell traveled to L.A. from Tampa, Fla., to attend the trial.

Prosecutors say that Buck, 66, solicited Black men who were poor, homeless or addicted to drugs to have sex and use crystal meth and other drugs during “party and play” sessions at his Laurel Avenue home. He lured them with promises of drugs or money, offering cash bonuses if they let him personally inject them, they say.

The government will seek to prove during the trial that Buck’s “modus operandi was to distribute drugs to Black men, in part because of the power he could exert over them as a wealthy white man,” Assistant U.S. Atty. Lindsay M. Bailey said in court papers.

Buck, she wrote, demeaned and dehumanized them with racial epithets, “verbalizing the sense of superiority and ownership he felt over these individuals and their bodies.”

“If they did not fully engage in this form of role-playing and following defendant’s every command, they would be harassed, abused, and cast out without previously agreed upon payment,” Bailey said.

Buck is charged in a nine-count indictment with providing the methamphetamine that killed Moore and Dean, enticement to travel for prostitution, distribution of methamphetamine and maintaining a drug den.

If convicted in either of the overdose deaths, Buck faces a minimum of 20 years in prison.

Ludlow Creary, an attorney for Buck, did not respond to a request for comment. Another Buck attorney said previously Buck was the target of a racially driven character attack and suggested he often helped people struggling with addiction or homelessness.

Prosecutors plan to call several witnesses to testify about their “party and play” encounters with Buck. One of them says Buck once slipped a tranquilizer into his drink, making him feel paralyzed, and when he awoke he found Buck injecting him, according to the U.S. attorney’s office.

During jury selection Tuesday, U.S. District Judge Christina A. Snyder asked potential jurors about their attitudes toward drug abuse. Several told of their own struggles with addiction, and several had friends or family who died of drug overdoses.

“It’s a lot for me to be in a case like this,” said one potential juror who broke down in tears as she told of a friend’s fatal overdose and her father’s addiction to crystal meth, cocaine and marijuana.

Opening statements are set to start Wednesday morning.

Buck, a longtime Democratic campaign donor, was widely known in West Hollywood politics long before his notoriety for the drug deaths. A onetime candidate for a seat on the West Hollywood City Council, he led the drive for the city’s 2011 ban on fur apparel.

In 2010, then-California gubernatorial candidate Meg Whitman was holding a political rally at a Hollywood hotel when from the front row a man started heckling her.

Moore’s overdose on July 27, 2017, turned Buck into a toxic political figure. Moore had flown from Houston to L.A. earlier that day at Buck’s expense.

“I have a guest who seems unresponsive,” Buck told a 911 dispatcher, according to a transcript of the call.

“Are they breathing?” the dispatcher asked.

“I got my neighbor over here giving him CPR, and he just said call 911,” Buck responded.

“I can’t find a pulse!” the neighbor shouted.

Moore was found naked on a mattress in Buck’s living room, and the apartment was littered with drug paraphernalia, including 24 syringes with brown residue and five glass pipes with white residue and burn marks, according to the Los Angeles County coroner’s report.

Moore died of an accidental meth overdose, the autopsy report concluded.

The Los Angeles County district attorney’s office declined to file charges, citing insufficient “admissible evidence.” Jackie Lacey, the L.A. County district attorney at the time, defended the decision, saying that sheriff’s deputies had no legal right to pick up the meth and paraphernalia that they saw in Buck’s apartment as emergency workers were trying to resuscitate Moore.

A year and a half after Moore’s death, Dean, who worked at Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills, died of an overdose in Buck’s apartment.

“I have a friend who’s unresponsive,” Buck told the 911 dispatcher, in a call eerily similar to the first. “I believe he did some drugs, and they were too much for him.”

In February, a month before his 55th birthday, Timothy Dean took the plunge into a rooftop pool in West Hollywood.

Dean’s death sparked protests by civil rights activists who accused authorities of failing to aggressively investigate and prosecute a politically well-connected white man suspected of preying on Black men.

In September 2019, a third man overdosed on methamphetamine in Buck’s apartment but survived. Buck was arrested on state charges of battery causing serious injury, administering methamphetamine and operating a drug house. Two days later, the federal charges were unsealed.

In the lead up to trial, Buck’s attorneys have revived the claim that deputies needed a warrant to search a tool chest in his apartment where drugs and paraphernalia were discovered. But Snyder has agreed with federal prosecutors that the evidence was “in plain view” and thus admissible.

“It still hurts,” Jackson said of her brother’s death. “I pray constantly — I wish I could wake up from a dream, and this is just a dream, and Tim is still here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.