- Share via

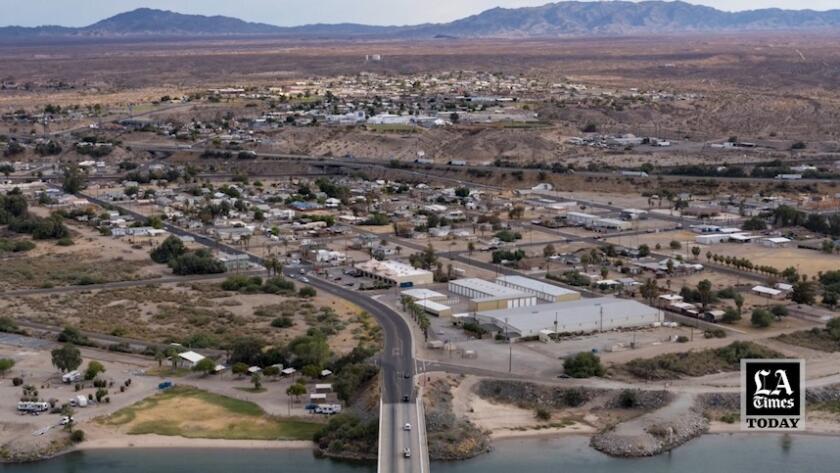

NEEDLES, Calif. — Rick Daniels lies awake at night worrying about a rusty contraption in a forlorn field, littered with discarded pipes and fire hydrants.

It is the only water pump in Needles that meets state water quality standards, running 23 hours a day to keep up with demand, according to Daniels, the city manager. That’s a thin margin in one of America’s hottest cities, an urban speck in the desert near California’s border with Arizona.

If this lone pump fails, 5,000 residents face the ultimate risk of taps running dry, as temperatures soar past 120 degrees and people need to gulp as much as two gallons daily. In June, a transient person died while sitting on a curb midday, one of about 10 people a year who succumb to heat, city officials say.

Across California and the West, the current drought is causing many wells to dry up, but few other communities are looking at their single water lifeline going to zero.

“We are incredibly vulnerable,” Daniels said. “We are talking about life and death.”

The Colorado River flows right through this isolated historic railroad town, carrying about 6 million gallons every minute. But under western water laws, the city can’t pull a single drop from the river.

Historically, the city has depended on four wells that draw from the river’s nearby aquifer.

That worked fine for decades until late last year, when California’s water authorities notified the city that three of its wells failed to meet state standards because of a naturally occurring mineral — manganese — that affects health. A May citation found the city had violated state water law and ordered a corrective plan by the end of this year.

The city says it can’t afford a fix, which would include a new well for $1.5 million.

So, Needles’ single well works around the clock. The city has three tanks that could keep water flowing for 24 to 36 hours if the pump stops — assuming everything else were to go just right. By comparison, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California requires its member water agencies to have a seven-day emergency supply.

Needles officials say state officials don’t appreciate their desperate situation and protested that the order could jeopardize public safety. The city wants to keep the decommissioned wells as a backup in case of emergency.

Eric Zúñiga, the district engineer at the State Water Resources Control Board who signed the citations, said the board is encouraging the city to make its system more redundant, either by filtering or treating the bad water or by finding new sources. In an email, he added that his citation does not forbid the city from using wells contaminated with manganese if it notifies customers, but city officials believe they will be forced to physically disconnect them.

It is doubtful that, in an emergency, the city would facilitate a mass casualty event by not somehow supplying water — even contaminated water or water taken unlawfully from the Colorado River. But it has entered unknown territory, a zone of risk where few other cities venture.

Daniels agrees, but adds, “This citation was outrageous, insensitive and out of touch.”

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

By all accounts, the city’s water system is decrepit. In 2020, a 16-inch city water main burst at a bridge abutment over I-40 and dumped roughly 500,000 gallons on the freeway, a main freight route from California ports. The spill halted eastbound traffic for hours until one lane was opened. It took days to remove 3-foot-thick mud.

A lot of California water agencies are in tough shape, because of aging infrastructure, drought, rising temperatures and political priorities lying elsewhere. Jay Lund, director of the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, said that California has about 9,000 regulated water utilities and that as many as 1,000 of those systems have problems of some type.

Decision-making authority is diluted. Municipal water managers make most decisions and report to regional water boards. The regional boards are overseen by the state water board. The Department of Water Resources controls the supply of surface water. The California Public Utilities Commission oversees rate setting and service. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has some jurisdiction over state operations. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation controls the Colorado River.

“We have quite a few chiefs looking over this deal,” Lund said. “If you are a regulator, you have all these systems all over the place, and you don’t have much staff.”

Needles, among the poorest communities in California, has always prided itself for persevering. But now an inhospitable climate is becoming unbearable in so many ways.

“Every time there is a heat wave, Needles is up there among the hottest temperatures of the day,” said Brian Lada, an Accuweather meteorologist. A ranking of the nation’s most blistering cities by Lada didn’t include Needles because it is too small, he said.

A housing survey found that 55% of the residents are on some form of welfare assistance. There isn’t a grocery market in town, though a well-stocked liquor store has a few aisles for canned goods and frozen food. A handful of cannabis dispensaries and shuttered 1950s-era motels cluster around the main drag, the historic Route 66.

The city’s economy and its tax revenue are hurt by its proximity to Arizona, which is right across the Colorado River, and Nevada. On a recent day, gasoline was selling in Needles for $5.19 a gallon, but across the bridge it was under $2.90. A Walmart is 12 miles up Highway 95 in Bullhead City, Ariz.

Many of the highly paid in Needles live in Nevada or Arizona, spending their California income out of state. BNSF railroad has a crew station in Needles with about 500 employees, but the vast majority live in Nevada or Arizona, city officials say. Indeed, nearly all cars in the BNSF employee parking lot have Arizona or Nevada license plates.

Calling Needles “remote” would be an understatement. The city is more than 200 miles from the county seat, San Bernardino. Its state senator lives farther away in the Central Valley. The nearest major California city is Barstow, 140 miles away. Las Vegas is 100 miles away. It isn’t clear what friends it would have in an emergency.

Even now, after begging for intervention, the city hasn’t gotten much help. Gov. Gavin Newsom, state legislators and its congressional representative either didn’t respond to letters or don’t offer much, according to Needles officials.

“We need help,” said Rainie Torrance, a city utility manager.

A nonprofit coalition of labor unions and contractors, known as Rebuild SoCal Partnership, has taken up the city’s cause. It has helped contact state officials and prepare grant requests. Marci Stanage, the group’s director for water and environmental relations, said she is surprised that nobody has responded to the city’s problems or her group’s efforts.

After visiting Needles to advise them on a new well, Dave Sorem, an engineer on the group’s board and vice president of a Baldwin Park construction firm, said: “The city is in more trouble than it realizes. California has a $76-billion budget surplus, but it can’t help out for a million-and-a-half-dollar well? Come on.”

The city’s single pump could fail for any number of reasons. Water wells have intake pipes at their bottoms, with screens to allow the water to flow into the pipe. The screens can collapse and plug the well, according to Bryan Hickstein, the city’s chief water operator. The steel well casings can collapse, he said, or the motor can burn out, as it did last year. The city had a spare motor, and a contractor rushed out from Anaheim with a crane.

The city’s problems began last November when the water board put the city on notice that three of its wells showed manganese levels above the maximum allowable level of 50 micrograms per liter. Then in May, the water board issued a citation, requiring a corrective action plan by the end of 2023.

Daniels said he complained about the list of requirements in the citation, and shortly after, the board issued a revised citation that moved the corrective action plan deadline to the end of 2021. Zúñiga, the water board engineer, said the original date was a typographical error and had nothing to do with comments from the city.

Manganese, not to be confused with magnesium, is a metal abundant in the Earth’s crust. At low levels, it is an essential nutrient for humans, but at elevated levels it poses undefined risks. The state established a maximum allowable level, citing “aesthetic” issues with high concentrations, which stain clothes, sinks and stucco. It also leaves water with a bitter taste. Iron was another aesthetic problem in the wells, but it is generally not high enough to be harmful.

Water toxicologists say there is growing evidence that at higher concentrations manganese can cause neurological disorders, particularly in young children.

“We are moving toward a regulated level,” said Donald Smith, a recognized national expert on manganese and a toxicology professor at UC Santa Cruz. “It is unclear whether a level of 50 micrograms per liter causes neurological effects. My professional opinion is that there is reason to be concerned. We don’t know what level is safe and what level is unsafe.”

California may be the only state to regulate manganese. Minnesota has a guidance limit of 100 micrograms per liter, twice California’s level. Zúñiga said he is not aware of any other states that regulate the metal.

Janice Paget, a board member of the Needles Chamber of Commerce, said most people in town aren’t aware of the manganese issue.

“I don’t even know what kind of side effect it causes,” she said.

Cost is a more common complaint, Paget said, noting that she and her husband, the only surgeon in Needles, had a water bill of $174 in June.

Drilling a new well would be one solution for Needles. The city hired a hydrologist who identified a site unlikely to be contaminated.

But the city doesn’t have the roughly $1.5 million needed to dig the well, Daniels said. As it is, utility customers are more than $300,000 behind on their bills.

“Our disadvantaged residents,” he said, “can’t afford a water rate increase.”

- Share via

Ralph Vartabedian

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.