Before a 4-year-old boy’s killing, authorities wavered on rescuing him

- Share via

Maggie Hernandez dialed Los Angeles County’s child abuse hotline on a spring afternoon in 2019.

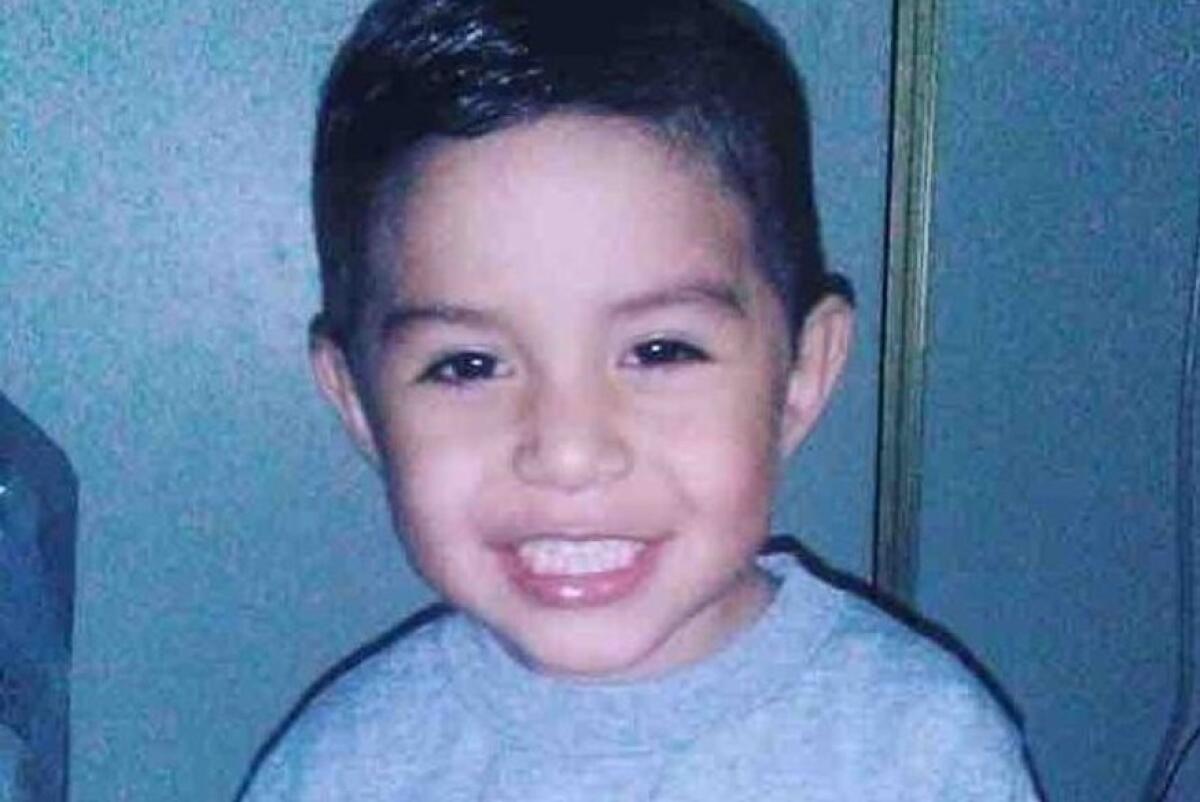

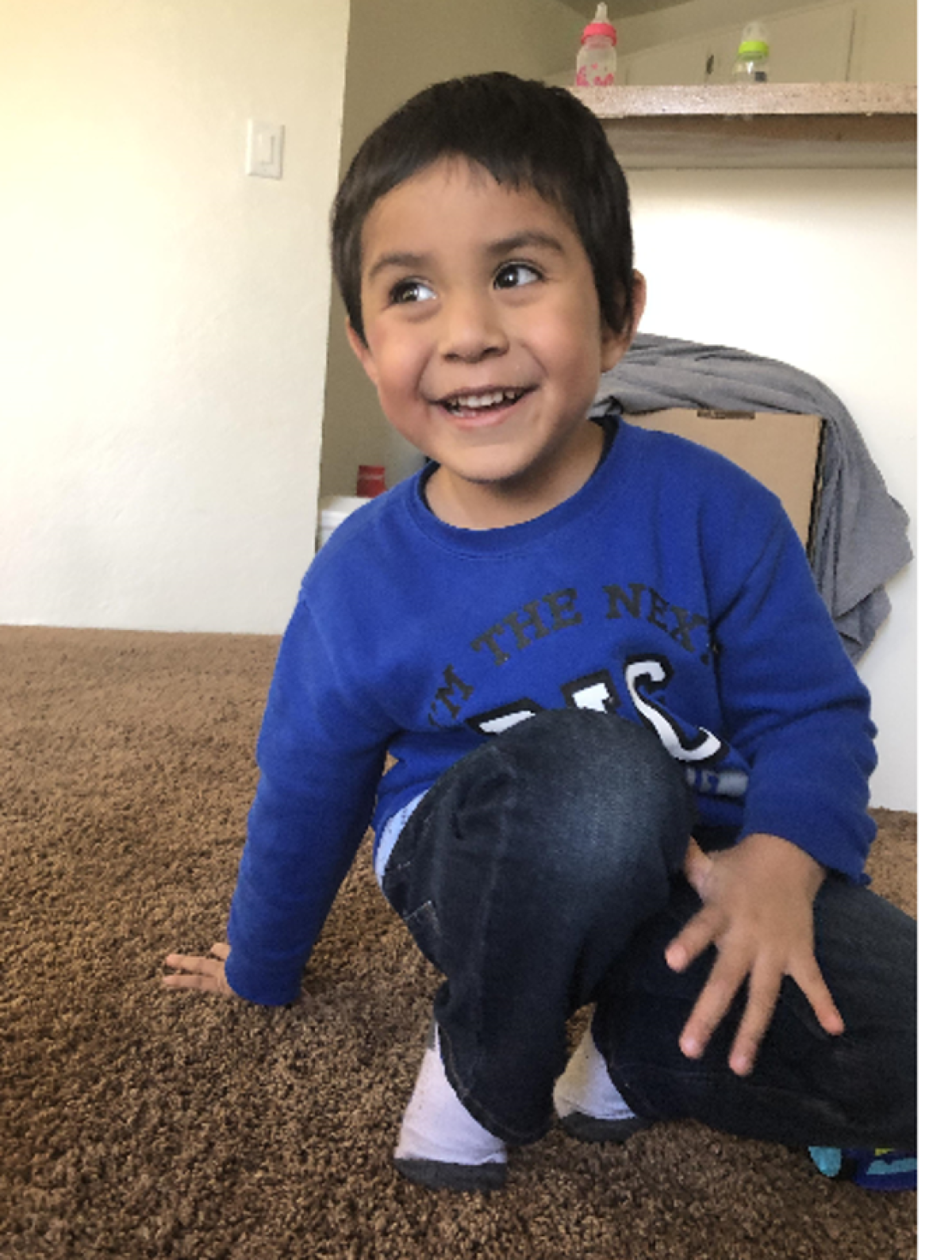

She said her niece’s son, Noah Cuatro, was losing weight and had thinning hair.

During an overnight stay with a relative, Noah had night terrors and complained that his butt was hurting, perhaps a sign of a rash or sex abuse, she said. Above all, Noah had changed from an exuberant boy to a fearful one.

“And when a child changes their, you know, their demeanor, I feel like something is going on,” Hernandez told the hotline. “He’s 4,” she said. “Nobody’s going to advocate for him.”

The call was the latest source of alarm for Susan Johnson, the Department of Children and Family Services caseworker tracking Noah. More than two years earlier, DCFS records show, his parents’ neglect led to the point where he was starving, weighing just 17 pounds and unable to walk. Authorities took Noah away then, but a commissioner had recently sent him back to his parents.

The call culminated in Johnson‘s securing a Juvenile Court order to again take Noah away and put him in protective custody. DCFS had 10 days to get Noah out and seen by a doctor, even if it required barging into the home with police. Carrying out that removal order could have saved Noah’s life.

Instead, DCFS ignored the order and kept Noah with his parents. He died less than two months later, on July 6, 2019. He was a month shy of his fifth birthday. His parents, Ursula Juarez and Jose Cuatro, now stand accused of murdering and torturing him.

An investigation by the Los Angeles Times and the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley found that errors, misjudgments and bureaucratic conflict within the child welfare system — including among top supervisors — blocked multiple opportunities to protect Noah.

His life and tragic death offer a sobering window into how race and ethnicity, cultural sensitivity, and trust collided inside the agency.

In Noah’s case, his parents and Johnson’s own colleagues accused her of bias and having “an agenda,” according to DCFS records and internal emails.

The charge of “bias” pointed to DCFS’ reckoning with a history of inappropriately separating children from their parents, especially in Black and brown families.

But without a way to effectively deal with those accusations in Noah’s case, the debate over bias paralyzed the agency, clouded the view of his family, and sidelined the staffers who knew him and his family best.

The months leading up to Noah’s death also raise questions about a signature policy implemented by the L.A. County Board of Supervisors and touted by DCFS Director Bobby Cagle. This policy, which guided administrators’ decisions, is in line with a national movement calling for a less adversarial approach to parents, respect for diversity, and a shift in focus away from the family’s weaknesses and toward its strengths.

A spate of child fatalities in the Antelope Valley — Gabriel Fernandez, Anthony Avalos and Noah Cuatro — has led to calls in recent years for more resources in the underserved region.

Despite Noah’s death, Cagle said in an interview that he saw no problems with DCFS’ current policies nor its handling of Noah’s case, and he refused to say whether discipline was imposed on any staff involved.

“I think my staff actually carried that process out well,” Cagle said. “It’s very difficult for, I think, the public especially to understand why those decisions were made, but I’m confident that the decisions that were made were the right ones.”

At the heart of the case is whether signs of Noah’s neglect and abuse were taken seriously enough. Some officials believe they couldn’t foresee a catastrophe.

“You went from virtually no physical abuse to the worst kind possible: The child was murdered,” said Michael Nash, who facilitates child protection oversight for the Board of Supervisors.

But the Times-UC Berkeley investigation found glaring red flags in the months before Noah’s death: the ignored removal order, the disregarded court order for a medical exam, the parents’ repeated failure to comply with the terms of their custody and an assessment cited in grand jury testimony that Noah’s mother showed traits of a sociopath.

Reporters also reviewed text messages among relatives discussing their concerns of abuse by Noah’s father as well as a deliberate effort to mislead social workers, underscoring the challenges faced by DCFS and the shortcomings of the agency’s investigation.

Noah’s great-grandmother remains frustrated and despondent, replaying her memory of the last time she saw him and his parting words: “Never forget me.”

“If they listened to the court order, he would still be alive,” Eva Hernandez said through tears. “He was such a beautiful little guy…. I hate the things that happened to him.”

Prosecutors announced Monday the parents of a Palmdale boy who died under suspicious circumstances in July will face murder and torture charges.

Cuatro and Juarez have each pleaded not guilty, and their attorneys declined to comment. This story draws from a review of Juvenile Court files, emails among DCFS staff and testimony from a grand jury proceeding that led to his parents’ indictment. The Press Freedom and Transparency practice at UC Irvine School of Law and The Times obtained the records via court orders.

On DCFS’ radar even before he was born

When Johnson took over Noah’s case around the fall of 2018, she inherited the supervision of a dysfunctional family whose members were either neglectful, powerless to help or unwilling to intervene.

Noah’s mother, Ursula Juarez, first met Jose Cuatro at John F. Kennedy High School in Granada Hills. Juarez gave birth to their first son when she was 18, Noah at 20, and a daughter at 23.

Noah’s birth in 2014 was different from that of his siblings. DCFS whisked him away at the hospital because the agency accused Juarez of abusing an infant half-sister, causing skull fractures.

He spent his first weeks of life cycling through foster homes before being placed at the San Fernando home of his great-grandmother, Eva Hernandez.

His parents forever felt DCFS had robbed them of the first months of caring for their son. And Noah formed perhaps the most enduring bond of his life while staying with Eva Hernandez, sometimes calling his great-grandmother “Mommy.”

When Noah was 9 months old, DCFS could not prove the abuse allegation against Juarez, and the Juvenile Court cleared him to live with his parents for the first time.

Once under their care, Noah’s health took a tailspin. Eight missed doctor’s appointments over the spring and summer of 2016 prompted Kaiser Permanente to alert L.A. County’s child abuse hotline of possible neglect.

Juarez blamed insurance problems. But a social worker verified Noah always had medical coverage, and she grew distressed: At 17 pounds, he had gained only a few ounces from February 2015 to October 2016. His muscles were deteriorating, and his inability to walk placed him in the first percentile for 2-year-old boys.

“He appeared very thin. His eyes were hollow,” said Jennifer Montano, who worked on Noah’s case at the time. Juarez said Noah ate too much, which made him vomit and thus not gain weight.

Caseworkers obtained a removal warrant for the second time, citing Noah’s dire condition and his parents’ neglect. In foster care, and later at Bithia’s House, a facility in the San Gabriel Valley for medically fragile children, he gained several pounds and the digestive troubles that Juarez had insisted he suffered had vanished.

During his stay at the Pomona facility, Noah’s development hastened.

“He was not quite caught up, but almost there. He was running around. He was sliding on the slide. He would call himself No-no,” said Michelle Thompson, the administrator at Bithia’s House. She forever remembered him as “such a ham” with a “wild mop of brown hair and a sweet, sweet disposition.”

Noah returned to live with his great-grandmother. He was a “bright little boy,” said Eva Hernandez, who recalled a visit to the doctor’s office where he corralled those in the waiting room into singing “Old McDonald.”

“Every day, he’d tell me, ‘Grandma, you know what time it is? It’s time for you to hold me and tell me you love me,’” she said.

But Noah’s parents wanted him back. Juarez protested that she would never intentionally starve her child and lamented that DCFS caused her to miss the first nine months of Noah’s life. She said she “just wanted to be one big family again.”

To reunite Noah with his parents, the court allowed supervised visits, then weekend stays.

Johnson’s predecessor on the case testified that Noah would wet the bed on the days before or after visiting Juarez and Cuatro, and wail and scream for up to 45 minutes, begging to stay with his great-grandmother.

“He would cry to me and tell me that ... ‘I don’t want to go with them,’” said Lizbeth Hernandez Aviles, the caseworker. She eventually made the unusual step of demoting herself within DCFS, citing how “very stressful” Noah’s case was, among other factors.

In 2018, after Noah turned 4, he told Hernandez Aviles that his parents’ home was a sad house “because they get angry and yell,” according to her case notes.

After his death, authorities uncovered text messages between the parents suggesting physical abuse around this time.

“Almost killed him so many times I had to do CPR for him to wake up,” Juarez texted Noah’s father in 2017. In another text, she wrote to Cuatro that he “almost killed his son and beat him.”

Eva Hernandez expressed concerns to DCFS that a permanent return to his parents would be catastrophic. By late 2018, Noah had lived apart from his parents for nearly two years. His turnaround was at a high-water mark: He was at the appropriate height and weight for his age, and doctors were thrilled.

She pleaded that Noah stay with her. “They never bonded with Noah,” Eva Hernandez remarked to a caseworker, “and I think that’s why they treat him the way they do.”

Noah didn’t want to leave. “This is my home. Grandma and Grandpa love me,” he told a DCFS staffer.

DCFS also opposed his going to live with Juarez and Cuatro. Johnson told the Juvenile Court commissioner, Steven Ipson, that the parents had not fully complied with visitation. Nor had they participated in therapy with Noah despite a court order to do so.

But Ipson said he saw “substantial” progress by the parents and sent Noah back to them. He imposed mandatory therapy and visits with Eva Hernandez, all to guard against the threats that had already harmed him.

“I get hit.… I do not get hit.”

When Johnson took over, her predecessor, Hernandez Aviles, warned her that Noah was the “target child.” The parents, according to Hernandez Aviles, were “habitual liars,” which was borne out by DCFS records and testimony: They lied about whether Noah had medical coverage, where they lived, and even two pregnancies.

Johnson was urged to conduct “unannounced” visits to see if parents were hiding mistreatment. Noah’s parents seemed to thwart those visits, DCFS records show. Johnson couldn’t access the family’s apartment complex in North Hills, or Juarez, then a manager-in-training at a nearby McDonalds, and Cuatro, an occasional construction worker, claimed to be at the mall, out of town, or otherwise unavailable.

When Johnson did make it inside, she saw that Noah and his siblings did not have their own beds and that the parents ignored the conditions imposed by the Juvenile Court. Noah, then 4, had not seen his great-grandmother, nor did he attend preschool or therapy.

In March 2019, Johnson arrived at the apartment where Cuatro and Juarez had claimed to be living. Cuatro’s sister answered the door and said her brother and his kids had not lived there for at least four months. Cuatro’s mother, Nuvia Barrios, said the family occasionally stayed there and confessed to being worried about her grandkids.

Noah was always hungry, according to Barrios, who worried about her grandchildren not being in school.

The following month, Maggie Hernandez, an aunt on the other side of Noah’s family, made her anonymous call to the child abuse hotline. She reported concerns that his “butt hurts” and that Juarez “wasn’t feeding him.”

“If he’s vocalizing something’s wrong and he’s having night terrors,” she said, “I feel like something’s going on.”

Johnson rushed to see Noah and saw marks on his right arm and neck; his left arm bore a “big bruise” and freshly applied lotion covered his back. Juarez said the cream was for eczema. Johnson was suspicious because she couldn’t see his skin.

Alone with Noah, Johnson asked what happened when he did something wrong.

“I get hit,” Noah replied. Johnson recalled in testimony that Noah seemed “startled,” as if he was surprised the words had tumbled out of his mouth. She pressed for details, and he backtracked: “I do not get hit.”

Sensing he had been coached, Johnson posed the same question. He again revealed physical abuse, then recanted.

On May 9, less than two months before Noah died, Johnson told the Juvenile Court that “many concerns have arisen from the family.” She said that the parents were isolating Noah, that it was “nearly impossible” to assess his well-being, and that she wanted the Juvenile Court to order the parents to receive mental health exams.

The same day, Johnson and her immediate supervisor huddled with a senior administrator at the Lancaster office, Shannon O’Brien.

“Because I was concerned about Noah’s safety,” Johnson later testified.

The parents had yet to comply with court-ordered therapy, they were not quickly responding to his medical needs, and Noah seemed coached during visits. Noah’s mother had also texted Johnson a photo of Noah’s back without cream that appeared to show bruising.

Asked if it was time to take Noah away for the third time, O’Brien was blunt to Johnson: “Get a warrant.”

‘Why would we hurt our baby?’

The task of probing Maggie Hernandez’s allegations of potential neglect and sexual abuse fell to Maggie Vasquez Ducos.

Johnson remained the caseworker in charge of long-term services. Vasquez Ducos was more temporary, part of the DCFS team that figures out whether abuse or neglect allegations are credible.

Like Johnson, she also drove to visit Noah and his family. There, Juarez gave her account of his bruising: Noah fell off the bunk bed and hit himself on the wood.

With a new DCFS staffer on the scene, Juarez also seized the opportunity to unload about the agency generally and Johnson specifically.

“Why would we hurt our baby when we just got him back?” Noah’s mother said. “I have had this case open for four years, and I have been told I’m good enough to only have my two kids but not Noah. How does that make sense?”

Vasquez Ducos wrote in her case notes that Noah’s mother had tears rolling down her face as she protested, “I don’t trust the Department.”

Noah, then 4, denied any sexual abuse. A medical exam found it “plausible” the blue and yellow bruises on his back and arms could have come from falling off the bunk bed.

Vasquez Ducos and her supervisor arrived at a finding of “inconclusive.”

During this investigation, Vasquez Ducos attempted to contact Noah’s grandfather but was unsuccessful. There’s no indication she reached any relatives.

Text messages uncovered after Noah’s death show that at the time, relatives were candidly expressing concerns within the family about Noah.

“At the end of the day, I know what’s going on isn’t right, and deep down inside theirs truth to the mistreatment of Noah,” said Juarez’s sister’s boyfriend in a text message.

Juarez’s sister theorized that Cuatro “has something against” Noah, otherwise he “wouldn’t be so aggressive.”

“When he kills that kid don’t come crying to me, because we told you so,” she said.

While all this was going on, Johnson worked with L.A. County lawyers to file the petition to remove Noah.

Ipson, the Juvenile Court commissioner, granted the order to take him away from his parents and have him undergo a medical or sexual abuse exam.

That didn’t happen.

Los Angeles County caseworkers allowed 4-year-old Noah Cuatro to remain in his parents’ home despite a court order in May — weeks before the Palmdale boy died under what authorities say are suspicious circumstances, according to two sources who have reviewed court documents.

She didn’t want a ‘dead kid on her watch’

As Ipson was examining the request to remove Noah, however, Johnson’s colleagues at the DCFS office in Lancaster began questioning whether such a measure was necessary.

Vasquez Ducos believed there was not enough evidence of danger to require taking Noah away. She also conveyed that Noah’s parents felt harmed and misunderstood by DCFS, and told her supervisor that Johnson “was harassing them,” as her supervisor, Keith Blyn, testified.

Like Noah’s mother, she started to view Johnson as biased in assessing the family, showing deference to Noah’s great-grandmother, according to emails among DCFS staff.

Her supervisor, Blyn, echoed this view in a private email to one of the administrators of the Lancaster office: “[Vasquez Ducos] feels like this stuff might be untrue and that the extended family (and even [Johnson]) may have an agenda.”

It is not uncommon for social workers reviewing a case to come to different conclusions. The system is designed to have checks and balances, especially on momentous decisions like child removal.

The case of 10-year-old Anthony Avalos exposes serious failures by the Los Angeles County child protection system to intervene before his death.

It’s ultimately up to DCFS’ chain of command to chart a path forward. The brass sided with Vasquez Ducos.

“From sitting in the room with both of them,” Blyn testified, Vasquez Ducos was “better able to articulate her viewpoint” than Johnson. He also said that DCFS management wanted to follow the core “practice model” that requires workers to remain focused on the positive, taking a better look at a family’s strengths and less at its weaknesses.

Johnson, the primary advocate for removal, felt that the time had passed for Noah’s parents to work through their chronic deficits while the boy suffered. But when she tried to speak in a meeting with colleagues in the Lancaster office, Johnson recounted, a supervisor elbowed her to remain quiet. At some point, she interjected that she didn’t want a “dead kid on her watch,” as Blyn later summarized in an email.

A top administrator at the Lancaster office, Nancy Bryden, decided to put a stop to the removal. She also wanted Johnson, a Black woman, replaced with a Spanish-speaking caseworker, Johnson later wrote in an email.

It wasn’t clear why. Noah, his parents and siblings are all Latino and spoke English. One person in the extended family spoke Spanish with limited English.

According to testimony and DCFS records, the final reason for keeping Noah with his mother and father was something of a paradox. A fresh allegation of abuse and domestic violence had come in from Noah’s great-grandmother, Eva Hernandez, so leaders wanted that investigated as well.

Johnson was instructed to withdraw the petition for a removal warrant, but it was too late. The court had already signed it. Still, Bryden instructed Johnson to refrain from carrying out Noah’s removal.

Johnson vented in an email to her immediate supervisor who was on vacation, “They seem to not believe that my concerns are valid.”

The following day, she tapped out a terse note of protest to a senior supervisor, expressing disagreement with keeping Noah at home.

Shannon O’Brien, who had previously urged removal, replied that there was “more investigatory work that needs to be done.”

Johnson elevated her concerns to a regional administrator who oversaw the office’s staff.

“Because I was upset,” Johnson testified. “I couldn’t believe that they did that. Nobody had ever taken me off a case like that.”

‘Traits of a sociopath’

Five days after the commissioner issued his order to remove Noah, Vasquez Ducos traveled to the family’s new apartment in Palmdale. Hernandez Aviles, who previously handled Noah’s case, joined her.

They found Noah had an injury on his upper cheek, and there were three different explanations of what led to it.

Juarez attributed the mark to kids rubbing a salty ice cube on him at a birthday party. Noah claimed it was a bug bite. Cuatro reminded Noah, “Remember you fell, we took you to the doctor, and they gave us ointment.”

During the visit, Noah “randomly” ran up to Hernandez Aviles, saying, “They feed me a lot,” “They take good care of me,” and “They love me.”

“Many of [the] child’s responses throughout the visit appeared coached,” she wrote in notes.

The DCFS team huddled again in late May to review Noah’s case. By then, Vasquez Ducos had interviewed some relatives; nearly all denied abuse.

During the discussion, Hernandez Aviles testified, she shared concerns about Noah, but colleagues favored a meeting between Noah’s parents and DCFS, not taking him away. She said this was in line with “a strength-based approach,” a reference to the core practice model promoted by agency leadership.

Asked about the injury Noah showed on his cheek, the conflicting accounts, and why this did not raise red flags, Hernandez Aviles said supervisors seemed inclined to think the parents would lie because of their history with DCFS.

Social workers have 10 days to take children from their homes after a commissioner issues a removal order; otherwise, they must alert the court.

But by mid-June, the final full month that Noah spent alive, 29 days had passed, and no one ever told the Juvenile Court that he remained with his parents.

In emails, colleagues across DCFS’ chain of command expressed confusion about who was responsible for the case and struggled to articulate why no one had removed Noah.

“We do need to have a staffing on how this needs to be explained that the warrant was approved but not served,” wrote Desiree Robinson Moody, a supervising social worker. “I want us to be able to submit a reply to court with a substantial reason why, and I am not with the full understanding as to why.”

Ultimately the task of explaining this to the Juvenile Court fell to Johnson, even though she was no longer assigned to Noah’s case and had opposed keeping him at home. When Johnson was questioned under oath why she updated the court, she replied: “You have to follow directions when you’re at work.”

She told Ipson that another allegation of sexual abuse of Noah and domestic violence required investigating, so that was why the removal was not carried out. She said an allegation of neglect was recently “substantiated.” She also told the court that a recent assessment showed a “very high risk” for abuse and neglect.

Johnson also informed the court about a troubling new fact: Juarez had just given birth to another baby boy.

The details of the birth were left out of the update to the court. At a Kaiser hospital in Panorama City, Juarez had claimed to be a surrogate, despite lacking any paperwork to back that up. She received no prenatal care and even tried to sneak out of the hospital.

Nazeli Oglukyan, a Kaiser social worker who had previously called DCFS about Juarez and her children, alerted the agency. Vasquez Ducos traveled to the hospital and was told the results of Kaiser’s psychiatric exam that indicated Juarez showed “traits of a sociopath.” Oglukyan said she was worried by Juarez’s contradictory accounts of her pregnancy, but Kaiser concluded Juarez was not suicidal, homicidal or in a state of psychosis.

Vasquez Ducos consulted with her supervisor and, exactly a month before Noah’s death, DCFS let Juarez go home with the newborn.

Briefed on the developments in Noah’s case, Ipson granted DCFS 30 more days to take a deeper look at the family. He also requested an interview with Eva Hernandez. Ipson did not respond to questions.

As June continued, it appeared no one in the Lancaster office had been designated to replace Johnson as the coordinator of services and decisions in the case.

Vasquez Ducos was effectively tasked with being the caseworker and said she would try to see Noah, but her relationship to the family was fraying.

“The mother is threatening me at the moment and is not happy with me therefore, I don’t know if she will comply or allow me to see her children,” she wrote in an email.

“As of now, the mother is resistant to contact and I am unsure if she will let us in the door at this point,” echoed Blyn, her supervisor.

Despite the allegation of sex abuse, for which DCFS policy requires a forensic exam, and the court ordering a medical or sexual abuse exam, none had occurred.

One supervisor, Robinson Moody, told Vasquez Ducos that she would “highly recommend” a forensic exam.

To Vasquez Ducos, however, it seemed no such exam was necessary. She said in an email that a forensic exam two months prior showed “normal findings,” even though that exam merely found it was “plausible” that Noah’s bruises came from a bunk bed. Vasquez Ducos also asserted that there were no allegations of sexual abuse, despite an allegation the prior month that DCFS categorized as sexual abuse. She asserted that relatives and witnesses had reported no concerns, omitting those on both sides of Noah’s family who shared worries with Johnson and on the hotline.

Vasquez Ducos completed what would be her final visit to Noah on June 28, 2019.

Investigators are trained to interview children alone and record details of the conversations. Her notes do not show a one-on-one interview, but Noah said he enjoyed swimming and he “appeared well in spirits,” according to case notes.

When she tried to confirm the date for a long-delayed meeting between the parents and DCFS, Cuatro was dismissive, saying they did not want “any further involvement” with the agency.

By early July, the final week of Noah’s life, the focus of DCFS’ scrutiny had veered from Noah’s parents to those who believed he was endangered.

A senior administrator accepted a finding of Vasquez Ducos’ investigation: that Johnson was biased toward Noah’s family and the “only area of great concern” was Juarez’s mental health, according to an email.

Eva Hernandez, who was a source of stability and affection in Noah’s life, was faulted for “causing [Johnson] to have doubt with the family.”

“Again, there was no evidence of any of the statements made by [Eva Hernandez] to be found true,” Vasquez Ducos said in a late June email.

Noah’s parents, meanwhile, were characterized as victims of DCFS. In a July 3 email, Vasquez Ducos described the parents as “overwhelmed,” and they were “just done dealing with us.”

“I feel like as a Department we have been picking on this family,” she wrote.

‘Help, please, somebody’

Sometime on July 5, a neighbor at the Mountain Shadows Apartments in Palmdale walked by the Cuatro family’s apartment and heard a child’s cries.

“‘No, Daddy, no,’… ‘Mommy.’”

After 6 p.m., Cuatro and Juarez made panicked 911 calls. “Help, please, somebody,” Cuatro told a dispatcher. They reported the boy had been swimming in the pool and stopped breathing.

Almost immediately, police and paramedics grew suspicious.

“Things were just not adding up to what the father had already told us — that this child is down in a pool for over 30 minutes, and all of a sudden now he’s dry with a pair of tan shorts that were not wet,” said firefighter paramedic Chad Sullivan.

Noah’s body also showed “mottling” around his neck, a sign of strangulation.

Juarez expressed disbelief, Sullivan recalled, while Cuatro “kept saying, ‘I’m sorry, I’m sorry.’”

In the emergency room, Det. Susan Velazquez found a boy with bruises across his chest, arms and legs, with a large mark on his forehead.

“You knew in your heart that there was something more that he couldn’t tell us, that his body was telling us a story, and we needed to figure out what was going on,” Velazquez said.

Homicide detectives are investigating the death of a 4-year-old Palmdale boy after his parents reported he had drowned.

Doctors and nurses rushed to revive the boy, first in the emergency room at Palmdale Regional Medical Center and later at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

No family members made it to his bedside.

Dr. John Marcum said he joined a group of doctors and nurses who held the boy’s hands in his final moments.

“We were with him as he left the earth,” Marcum said.

“I should have done more.... I failed him’

The full scope of DCFS’ missed opportunities came into relief six months after Noah died, when L.A. County prosecutors summoned his family, social workers and medical experts to testify before a grand jury.

Dr. Carol Berkowitz, a UCLA pediatrician, said Noah had “so many injuries” but concluded Noah died from suffocation.

Berkowitz also found rib fractures that had occurred at least two weeks before he died, possibly longer.

“It takes significant force to fracture them, especially to fracture so many ribs and to fracture them on both sides,” Berkowitz testified.

Dr. Lawrence Nguyen, an L.A. County medical examiner, found bony deposits on a few of Noah’s ribs, showing older fractures that had since healed. “This would be considered chronic injury,” he added.

Experts also found trauma on the boy’s rectum but could not determine what had penetrated him.

One by one, relatives of Noah’s parents took the stand, recounting concerns about the boy.

Before 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez was allegedly beaten to death by his mother and her boyfriend, they doused him with pepper spray, forced him to eat his own vomit and locked him in a cabinet with a sock stuffed in his mouth to muffle his screams, according to court records made public Monday.

Juarez’s sister, Stephanie Juarez, admitted she lied to the caseworker investigating abuse.

“I dealt with DCFS a lot in my life, so I know what it’s like,” she said, later adding, “I should have done more.... I failed him.”

Deputy Dist. Atty. Jon Hatami summoned several DCFS staffers who worked on Noah’s case, including Vasquez Ducos and her supervisor, Blyn. None of the high-ranking DCFS administrators testified.

“The County and DCFS put a lot of roadblocks in front of me. Even the ones I called [to testify] were difficult to get into court,” Hatami said.

Asked if a physician ever had performed a sexual abuse exam on Noah, which was part of the commissioner’s order to take him away, Vasquez Ducos responded, “No.”

Both acknowledged they had not actually read Johnson’s 26-page filing to the juvenile court to remove Noah, despite opposing it.

Stunned, the prosecutor asked Vasquez Ducos, “You’re telling this jury that you decided not to follow the removal order that you never read? Is that accurate?”

“Yes,” she said, after explaining, “I read it after he passed away.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.