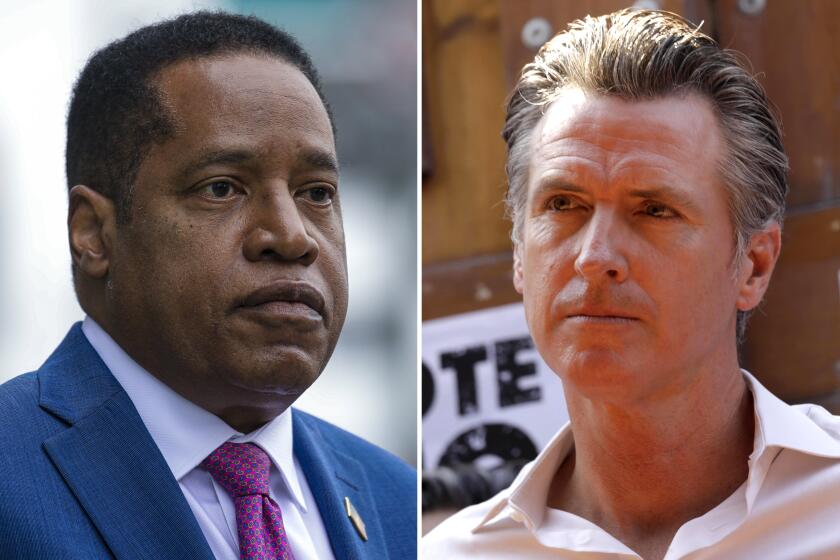

Larry Elder calls himself ‘Sage From South Central.’ But his ties to Black L.A. are fraught

- Share via

Two weeks ago, Larry Elder took Fox News’ Laura Ingraham and a camera crew to his old neighborhood. The interview was promoted as a tour of South-Central but viewers didn’t get scenes of the gubernatorial candidate pressing the flesh in Leimert Park, Watts or even Hyde Park where he grew up.

Instead, they were treated to carefully staged shots of Elder in front of his childhood home and Crenshaw High School, his alma mater. Standing in front of Crenshaw’s brick façade, Elder declared proudly to Ingraham: “I was born and raised here. I’m from the ’hood.”

The self-proclaimed “Sage From South Central” has embraced his origin story as a defense of racial politics. His critics say he’s made a career of upbraiding Black people to white audiences. They say he’s the Black face of white supremacy and his proposals would harm Black and Latino Californians.

Elder answers with where he’s from.

“Do I look like a white supremacist?” he asks in a new ad. “I walked those hard streets.”

As for his old neighborhood, Elder said he’s seen no evidence that voters here dislike him.

“A 37-year-old man came up to me and told me he was voting for me,” he told The Times about people he met during the taping for Fox News. “And some people came out of the house and told me that they were voting for me.”

But Elder has struggled to gain wide support in his old neighborhood in his quest to become California’s first Black governor.

Many Black voters here have heard him deny the existence of systemic anti-Black racism, have read his defenses of former President Trump and promotion of the birther lie that former President Obama was born in Kenya. They remember that Elder published a book in 2008 titled “Stupid Black Men.” More recently, Black voters have heard his case for reparations to the descendants of slave owners who lost their “property” when enslaved Black people were emancipated.

“I haven’t seen him take any initiative or try to organize anything for Black Americans in the community,” said Ernest Moore, a high school classmate.

“Larry Elder is not welcome anywhere in South-Central,” added former friend and collaborator Najee Ali.

Earl Ofari Hutchinson, a community leader and one of Elder’s longtime critics, calls the “sage” title “a phony, self-serving tag to get street cred.”

Elder dismissed the criticism but concedes that the moniker doesn’t carry much meaning.

“I didn’t think very much about it,” he said. “I probably came up with it within a few seconds of being on the air and it stuck. People call me that, but I can’t say there’s anything deep behind it.”

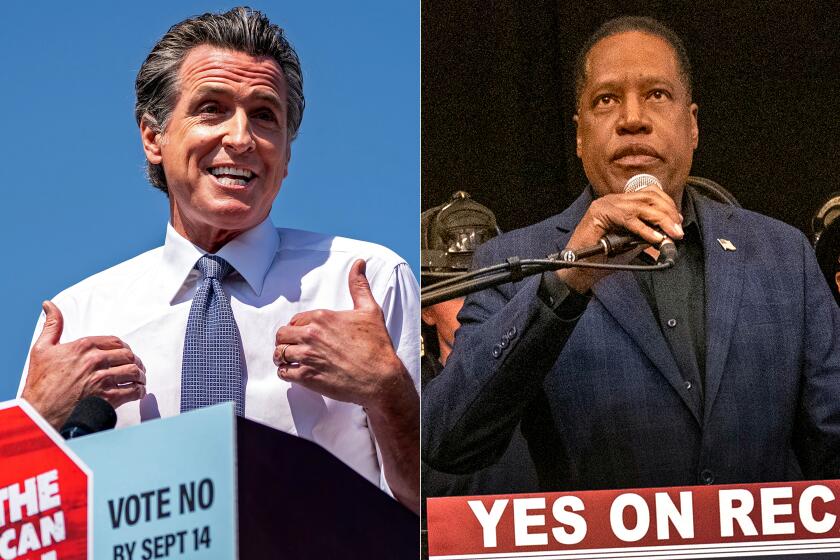

Here’s a look at The Times’ coverage of the California governor and the front-runner in the race to replace him should voters choose a recall.

Elder grew up in Hyde Park, a section of what was once called South-Central. The term fell out of use in recent years but it was once synonymous with Black Los Angeles and came to be associated with a part of the city especially hard hit by drugs, despair and gang violence in the 1980s and ’90s.

But it was a solidly working-class neighborhood in the 1960s and ’70s, when he was coming of age.

His family had a modest home with a garage, a manicured frontyard, and a backyard with an apple tree. Folks in the neighborhood were “house proud,” said Elder, and had traditional values. “Most of the kids in my neighborhood had mothers and fathers in the house ... People worked hard.”

A close look at Larry Elder, the top challenger in the California recall election: his life, his beliefs and his sudden political rise.

According to Elder, his family helped integrate the neighborhood, but white neighbors started to move away.

“My mother kind of explained to me why people were moving and I was surprised about that because I didn’t feel that I was threatening,” he said. “I didn’t feel that people should be fearful but a lot of people were and left.”

Larry Elder leapfrogs the others vying to replace Newsom, with provocative stances from firing teachers to downplaying the dangers of secondhand smoke.

Elder claims the changing demographics of the neighborhood didn’t make much of an impression on him — he was too busy riding his bike and playing Little League Baseball — but he did miss his white friends who left.

“I remember their names,” he said proudly. “One was named Carl Carrion, and one was Dennis Livermore. One was named Carmen Donard, Karen Pace.”

It was the period of “white flight,” the mass exodus of white families from cities to the suburbs starting in the 1950s as Black families like the Elders moved in. But Elder believes his friends had another reason to move. He said there was a minority of Black kids that “terrorized” his white friends.

“Many of them felt bullied,” he explained. “And I know they went home and told their parents they were bullied and their parents moved them out when they finished elementary school.”

By the time Elder got to Crenshaw, the high school and his neighborhood were predominantly Black. He wasn’t active in campus life, focusing instead on his academics, which helped him earn admission to Brown University.

Rommel Agee was on the varsity basketball team at Crenshaw and graduated in 1970 alongside Elder. He remembers his old classmate as not “politically involved” at a time when the Black Power movement was at its peak.

The former Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy and investigator with the L.A. County public defender’s office said he’s impressed with his old classmate’s accomplishments, but he doesn’t support Elder’s candidacy because he’s just too far right.

“I’ll smile if he becomes governor. And I’ll say, ‘Damn,’” said Agee. “He’s a brother — he knows he’s Black — but sometimes, cats like him from our generation look down on other Black people. They adopt an attitude that they ... achieved some success, so other Blacks who haven’t are just lazy. That’s not the case.”

The leading California recall candidate won’t waver, even when it costs him listeners, and his best friend. Now talk radio standout wants to replace Gavin Newsom as governor of California.

Moore was a class behind Elder. He taught adult education within the Los Angeles Unified School District for more than a decade before starting his own real estate business.

“I think most Black people know that Larry Elder is a sellout,” Moore said bluntly.

Opposition to Elder in Black L.A. goes back to the mid-’90s when he launched a radio show on KABC. Community leaders like Congresswomen Karen Bass and Maxine Waters, both Democrats representing Los Angeles, found the program so offensive that they refused to appear as guests.

But Elder maintained an audience and moved from one opportunity to the next — from a radio show to a short-lived TV show, to a podcast.

Ali was one of very few to break ranks and appear as a guest on Elder’s radio show. Over the years, the two became close.

But Ali said they fell out nearly a decade ago after an on-air debate in which Elder defended George Zimmerman, the man who fatally shot Black teenager Trayvon Martin, who was unarmed, in 2012. A Florida jury acquitted Zimmerman in 2013 of all charges in the killing.

Ali said he and Elder haven’t spoken since.

“Anyone that can defend the murder of Trayvon Martin can’t be someone I can be friends with,” said Ali, a longtime South L.A. activist.

Ali adds that, looking back at the time when he was part of Elder’s circle, he realizes that he was almost always the only other Black person there.

“Larry Elder lives in a white world. He really has just a handful of Black friends,” he said.

A spokesperson for Elder said in a statement to The Times: “Larry chooses his friends by the content of their character, not by the color of their skin. He has no race quota when it comes to friendship. When he becomes governor, he will be governor for all Californians, not just governor of certain races or ethnicities.”

Though polling shows only a small percentage of Black voters support his run for governor, his approach has attracted some, like D’Angelo LaVelle, a Black resident of downtown L.A. whose main concerns are homelessness and COVID-related mandates.

“He has a sense of urgency and talks about declaring homelessness an emergency. I also like his position against the mask mandate,” LaVelle said of Elder. “Giving people an option correlates more with my beliefs.”

Michael Mahdi, a Black voter in Pasadena, says he’s voting for Elder because he’s fed up with Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Democratic Party. Mahdi began voting Republican with Trump, who he believes won reelection, and he sees Elder as a continuation of the former president’s legacy. He likes his position against mask and vaccination mandates and thinks Elder could help improve public education.

“Sometimes it takes the common person that isn’t poisoned by the political machines to come out and do something,” Mahdi said.

“I think the measure of how close I am to Black folks ought to be how I articulate the issues,” Elder told The Times. “And whether or not I’m advancing issues that improve the lot of all people, including Black people.”

He said he wants to use the bully pulpit of government to support police and put a focus on rising crime. He’s also an advocate for charter schools and “school choice” and says he’ll continue to champion families and hard work.

“I don’t know how that makes me not connected to the Black community,” Elder said. “I’m talking about regular people — they know the quality of schools is bad. They know that crime is affecting them disproportionately. They know that this defund the police movement is ridiculous.”

Elder, by far the leading candidate to replace Newsom if the recall passes, is unlikely to triumph based on how people in his old neighborhood will vote. Then again, his success never depended much on what people in places like South L.A. thought about him.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.