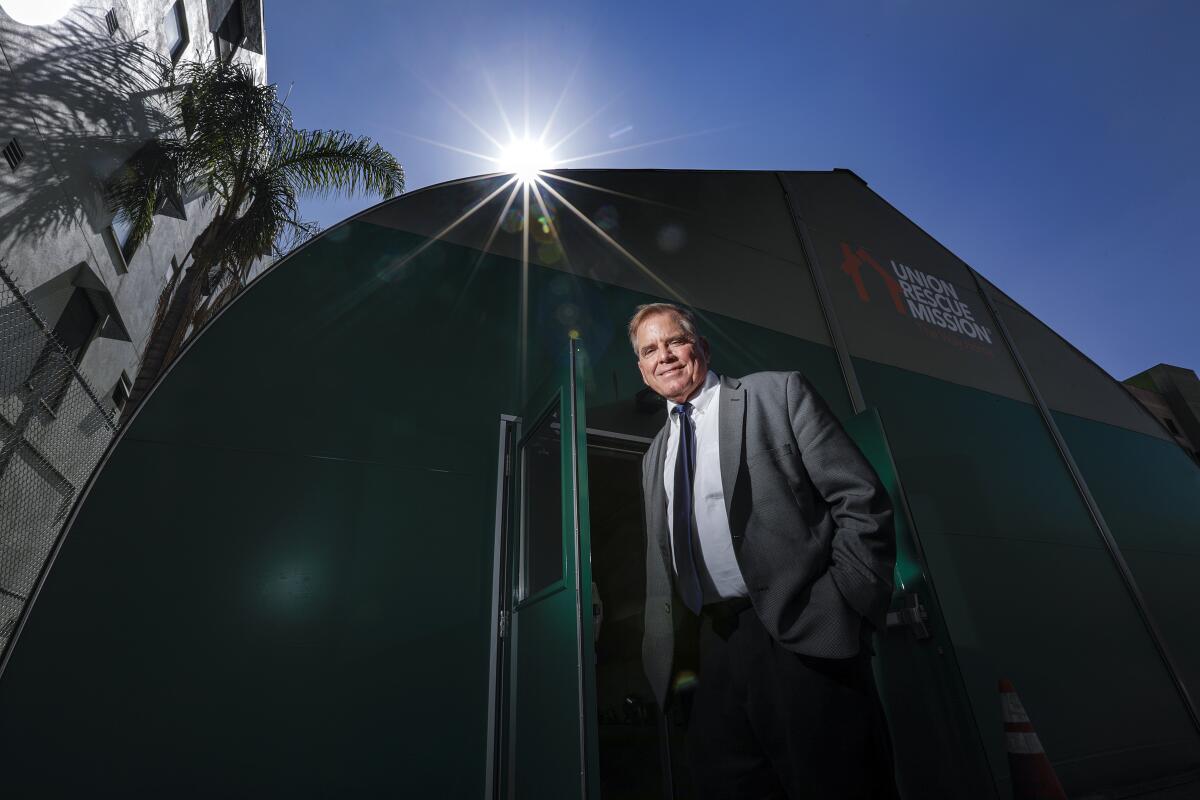

He’s no Dr. Drew, but Andy Bales could shake up L.A.’s homeless advocacy establishment

- Share via

After her first nominee, a celebrity doctor, was met with fierce moral outrage, Los Angeles County Supervisor Kathryn Barger is trying again to bring a contrarian voice to the 10-member Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority commission.

This time, it might actually work.

On Tuesday, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors will vote on Barger’s LAHSA nominee, the Rev. Andy Bales, president and chief executive of the Union Rescue Mission on skid row, who for years has denounced Los Angeles homelessness policy. Bales criticizes the prevailing strategy known as “housing first,” which seeks to remove barriers such as sobriety requirements and move homeless people from the street into individual homes either directly or after short shelter stays.

Barger said that while she supports the “housing first” approach, it cannot address “all that ails those on the street,” and she thinks Bales will bring a street-level perspective to the commission.

“The more people you have providing solutions and thoughts, the better system we’re going to have to address this problem,” Barger, the only Republican on the Board of Supervisors, said. “And I think to have someone not of like mind is not a bad thing.”

Barger originally recommended Dr. David Drew Pinsky, more commonly known as “Dr. Drew,” to the LAHSA commission in April but pulled the nomination after massive opposition from homeless advocates.

Dr. Drew Pinsky is a trained physician with decades of experience treating mental illness and substance abuse, says L.A. County Supervisor Kathryn Barger.

Bales’ relationship with Barger goes back to 2007 when, as a deputy to then-Supervisor Mike Antonovich, she helped smooth the way for the mission’s development of a center for women and children in Sylmar. He calls her “a real hero in my eyes.”

Originally from Des Moines, Bales, 63, was teaching in a Christian school there in 1985 when he decided to dedicate his life to serving people living on the streets. He was ordained in the First Federated Church in Des Moines in 1989. Now living in Pasadena, he and his wife, Bonnie, a nurse, have raised six children and hosted 25 foster children. Bales, who has Type 1 diabetes, lost his lower right leg to flesh-eating infections he acquired on the streets of skid row and later had to have his lower left leg amputated.

Union Rescue Mission director Andy Bales is indefatigable, despite major health challenges.

He led other nonprofits in Des Moines and his current home, Pasadena, before taking on leadership of the Union Rescue Mission in 2005.

Union Rescue Mission, founded in 1891 to dispense food and clothing from gospel wagons, is a privately funded provider of homeless services that today occupies a five-story building in the 500 block of South San Pedro Street, in the heart of skid row. It practices a faith-based “recovery model” offering immediate shelter, healthcare and life skills training for up to 1,000 clients.

According to its tax filing, it offers a 12-month intensive program that includes 2,000 hours of a biblical 12-step study, recovery classes, work therapy, counseling and physical fitness classes, followed by a transitional program of 6 to 24 months.

Under Bales’ leadership since 2005, Union Rescue Mission has opened the Hope Gardens Family Center, the satellite in Sylmar for senior women and mothers with children, and expanded its fundraising and solidified its mission of recovery in a Christian context.

In 2011, Bales won his board’s approval for the Gateway Program to “instill a greater sense of responsibility and dignity” by charging a small fee for long-term shelter.

Bales faults the permanent housing strategy both for leaving people on the street for years because there is insufficient housing and for allowing what he views as chaotic conditions when residents in those homes continue to use alcohol or drugs.

In an interview, he said he lovingly refers to the mission’s long-term housing “as our permanent supportive housing — the sober version — because we believe in creating environments where people can stay sober and recover in safe environments. And that’s one thing that I want to emphasize is there’s a missing link in the continuum of housing that LAHSA currently has.”

While that posture has made Bales an outsider in the secular nonprofit milieu of current homeless policy, his unquestioned passion and commitment to serving homeless people has insulated him from the wave of opposition that derailed Barger’s first choice of Pinsky.

In recent years, Pinsky has argued that the homelessness crisis is not driven by a lack of housing but by mental illness and addiction.

Los Angeles has undertaken a major shift in its approach to homelessness, one that puts a priority on clearing unsightly street encampments.

Barger pulled Pinsky’s nomination amid the outcry — and rumblings that her colleagues on the Board of Supervisors would not support the appointment if it came to a vote.

It’s rare for supervisorial appointments to local boards to cause controversy and even more uncommon for them not to receive unanimous approval.

The LAHSA Commission, which has authority to make financial, planning and program policies, has 10 members, five appointed by county supervisors, and the other five by the L.A. mayor and City Council.

It’s unclear how much power Bales could have as a single member, and even those who differ with him on strategy declined to find fault with his appointment, at least publicly.

Nan Roman, chief executive of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, didn’t criticize Bales’ appointment but suggested in an interview that it wouldn’t be helpful to have a commissioner advocating for a particular recovery model.

She said that it can be helpful for faith leaders’ voices to be heard but that they must be open to listening to data that show their ideas, such as Bales’ support for transitional housing, might not work for everyone. Research has found transitional housing to be expensive and not as effective as permanent housing.

Bales said he has no intent to be disruptive.

“So the first step is to listen,” he said. “And second is to, you know, gently and humbly share my ideas in a way that they will be welcomed and at least heard.”

“I hope,” he added, “there’s room for a faith-filled person who believes in recovery and believes in immediate housing or shelter over the heads of everyone in L.A., not just a few, as is currently being practiced in. ... A contrary voice is sometimes needed to think about things differently.”

Bales supported Pinsky’s nomination, and when it was pulled, blamed “cancel culture” and the “echo chamber” of advocates for housing first and harm reduction.

“It kind of told me I also would not be welcomed because I believe in recovery and people that are homeless with addictions — whether the addiction developed because of it or led to it — the addiction still needs to be addressed for them to live a whole healthy complete life,” Bales told Newsweek in April.

His appointment is expected to be approved at Tuesday’s supervisors’ meeting.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.