He sued SeaWorld to liberate the whales. Then he started getting postcards from them

- Share via

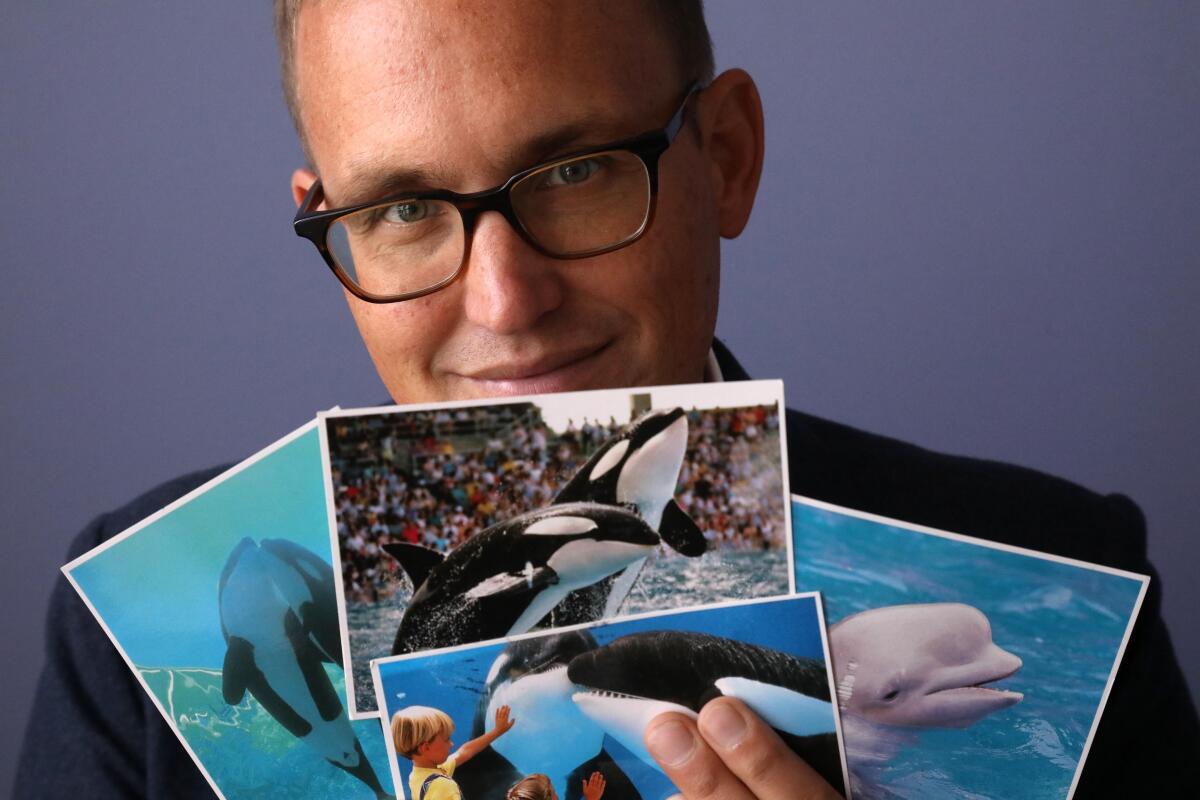

In 2018, Matthew Strugar received a postcard from a whale.

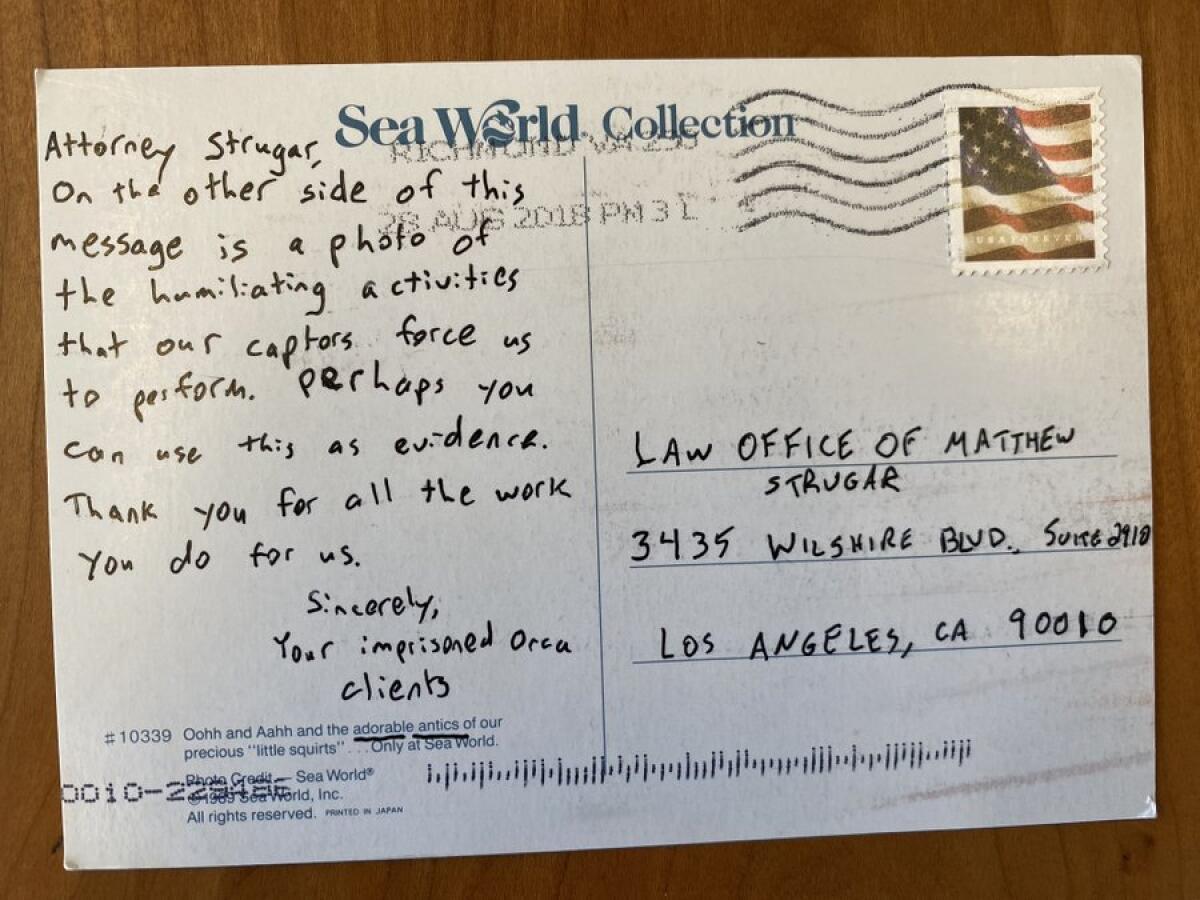

The card came out of an old SeaWorld tourist pack, the kind with glossy pictures of animals doing tricks, purchased for excited kids by worn-down parents then tossed in a drawer when vacation is over. Its front showed two orcas, one big, one juvenile, jumping gracefully from the confines of their chlorine-blue pool as sunburnt 1980s patrons in tank tops snapped photos and gawked.

The back carried a plea for help:

“On the other side of this message is a photo of the humiliating activities that our captors force us to perform. Perhaps you can use this as evidence. Thank you for all the work you do for us. Sincerely, Your imprisoned orca clients.”

It was not the only time the whales wrote.

Strugar, a civil and animal rights attorney in Los Angeles, had made waves in the animal rights scene eight years earlier by suing SeaWorld on behalf of five orcas held in captivity. He argued their confinement and forced performances violated the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment prohibition of slavery and involuntary servitude.

The suit was lambasted by some as more stunt than law, and dismissed by a judge who ruled the amendment applied only to humans.

Strugar said he did it on behalf of PETA’s Foundation to Support Animal Protection, to raise awareness of what he considers the brutality of holding animals like the orcas in unnatural settings that he argued can harm their physical and mental health.

Despite its legal downfall, the suit marked the beginning of years of negative publicity and financial hardship for SeaWorld, which eventually pivoted away from its reliance on large animal shows.

“There are sort of creative ways to use the legal process to advance movements and points,” Strugar said. He was gratified that the judge heard his logic and “didn’t take it unseriously.”

The whales seemed to agree, and Strugar was tickled to hear from them.

For the next three years, they kept sending him vintage postcards — along with some signed by SeaWorld’s dolphins and seals and flamingos — in all nearly a dozen missives from mysterious marine correspondents alternately thanking him for his help or begging him for more.

“It was kind of a delight,” he said. “I don’t want to call it a prank because it feels like almost an art project.”

It was a lighthearted mystery that didn’t seem to end, even during the pandemic. Whenever one arrived at his Koreatown office, he would call his fellow lawyers in to read it.

The postcards came sporadically, always from different places — New York City, Chicago, Pennsylvania. Even one from his hometown in Richmond, Va. The handwriting changed, too.

“Attorney Strugar — Thank you so much for the defense of us all. You’re an incredible ally to so many, but especially us. We appreciate you,” a beluga whale wrote in red ballpoint pen with loopy, feminine script shortly after the first card arrived.

Another one from the red-pen writer showed a flock of flamingos under palm trees.

“Dear Matthew, (We hope we can call you that), just a note to say thank you for advancing the rights of non-human animals. Years later the impact continues. Yours in struggle, Flock 7.”

Who, Strugar wondered, was sending them? Someone who knew him? Someone who didn’t? Which scenario was weirder? Part of him didn’t want to know — didn’t want to ruin the game with a good guess.

The cards grew more pointed, carrying the desperate yet informed tone that is common in the letters prisoners send to journalists and lawyers — “jail mail,” as it’s sometimes dubbed. They often addressed him with the formal “Attorney Strugar,” a greeting that made him laugh because incarcerated people do the same.

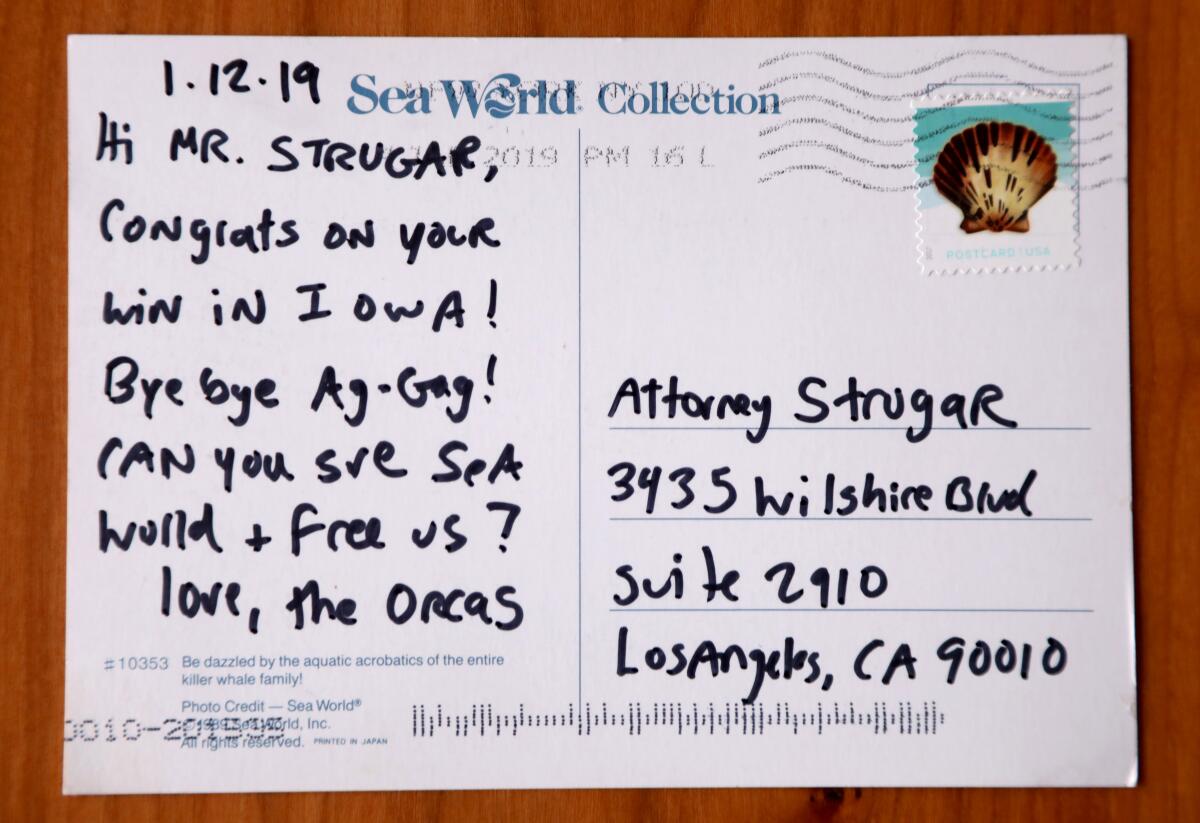

One parsed the legal nuances around claims of unjust confinement, debating which constitutional amendment applied to their situation — the one prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment, or the one that protects against being unfairly detained. Its front pictured two young boys with their hands on the glass pane of an orca tank as the whales inside, mouths open and teeth bared, seemed to look straight back at them. The tight black script had misspellings, dropped capital letters and underlined the important words.

“Counsel, we’d like to retain your services for a class action for an 8th Amendment conditions of confinement claim. Though it is arguebly a 14th Amendmat claim, as we have not been convicted of anything! We are innocent! Both as a legal matter and as a moral issue. We’re also interested in suing for them using our likeness on this postcard. they talk to us. but they don’t listen. we are begging these children to free us! Sincerely, The whales.”

His favorite was from a sea lion who claimed he had already filed documents with the court “pro se,” Latin for “on one’s own behalf,” as many incarcerated people without lawyers are forced to do.

“Dear Mr. Strugar, I got your name from some of the other guys in here. They said you did good work for them on some of their cases. There aren’t many lawyers that take these kinds of cases, so I’m hoping you can help. I filed suit pro se and will send you the paperwork. Sincerely, the Superstar Sea Lion.”

::

By 2021, the secretive sender was coming to the end of his pack. He had found the postcards, purchased on spring break in 9th grade, in a box of his childhood possessions, stored in his parents’ basement until they made him clean it out as they prepared to move. He didn’t like throwing away useful things, but a quick internet search showed the cards had little value. Nobody wanted them, even as a giveaway. Then he started thinking of Strugar and his whales.

Brad Thomson had met Strugar at a conference for the National Lawyers Guild, a left-leaning organization best known for the legal monitors it sends to protect protesters’ rights at rallies and marches. The two shared passions for underdogs, fighting “the man” and not eating animals. Strugar, a kidney donor, is vegan, like Thomson. Both are civil rights lawyers who came to their activism through the socially conscious punk rock scene of the 1980s and beyond.

Before law school, Strugar crossed the U.S. 13 times in one calendar year as tour manager for the (International) Noise Conspiracy, an anti-capitalist Swedish punk band.

Thomson, who started out as a paralegal and private investigator for the People’s Law Office in Chicago, a legendary firm that represented the Black Panther Party, has long loved bands such as Propagandhi, whose lyrics are anthems of the far left. “Is this class war? Yes, this is class war.... (We’re): 1) born 2) hired 3) disposed,” screams one popular song.

Like Strugar, Thomson sought out tough cases, ones where he saw injustice and powerlessness. While he was getting his law degree, he became prison pen pals with members of MOVE — the radical Black revolutionary group from Philadelphia that eschewed technology, consumerism and government.

The MOVE 9, as the media dubbed them, had been sentenced to up to 100 years each for a controversial 1978 police raid on their home that left one officer dead — though the MOVE 9 denied they fired weapons (they argued the shot that killed the officer came from a different building). When the seven living members came up for parole hearings beginning in 2018, Thomson offered legal help free of charge. All seven won their freedom after decades in prison.

A fan of “The Office,” Thomson started thinking of the postcards as a “Güten Pränken,” a phrase coined in the finale of the sitcom by Jim Halpert, the character played by John Krasinski, for gags he played on a colleague.

“It’s hard to pull off a prank without being mean, and I certainly didn’t want anything about this to be mean-spirited toward Matthew or to make light out of anything that was happening to people in prisons or animals in captivity,” Thomson said.

But he “quickly realized that a lot of the joke relied on the mystery of it,” he said. “If I just wrote these cards pretending to be a dolphin and Matthew knew it was coming from me, it would be mildly funny.”

So he enlisted friends. The cards with loopy red script came from civil rights attorney Sharlyn Grace, who helped in the fight to make Illinois the first state to end cash bail, and who knew Strugar from legal circles.

SeaWorld Entertainment Chief Executive Joel Manby is stepping down after failing to deliver a rebound in sliding attendance and revenues that have dogged the company years after the release of the anti-animal captivity film “Blackfish.”

Daniel McGowan, a former Earth Liberation Front activist who served time in federal prison after being convicted of setting fire to Oregon lumber company facilities in the 1990s, was enlisted to send two cards from New York, written in chunky black marker. Strugar had represented him in a civil case against the federal prison system.

Once, while incarcerated, McGowan became annoyed at a visitor who made fun of him for reading “The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” thinking it lowbrow. McGowan spent the next four years convincing people to help him repeatedly “Rickroll” the friend, an online joke in which the mark is tricked into clicking on a hyperlink that leads to English singer Rick Astley’s music video for the 1987 hit “Never Gonna Give You Up.”

But his past has left him mistrustful. When a reporter contacted McGowan, who now works for the American Civil Liberties Union, to ask about his part in the Thomson scheme, he was certain the call was a setup.

“Am I getting pranked?” he asked repeatedly. “I wouldn’t put it past either of them.”

::

Last month, Strugar stopped in Chicago during a cross-country train trip and had dinner with Thomson and Grace — a rare visit in the time of COVID-19. Thomson decided it was time for the reveal.

As they shared a plate of vegan nachos before a Bulls game, he pulled out the final card. Strugar never saw it coming.

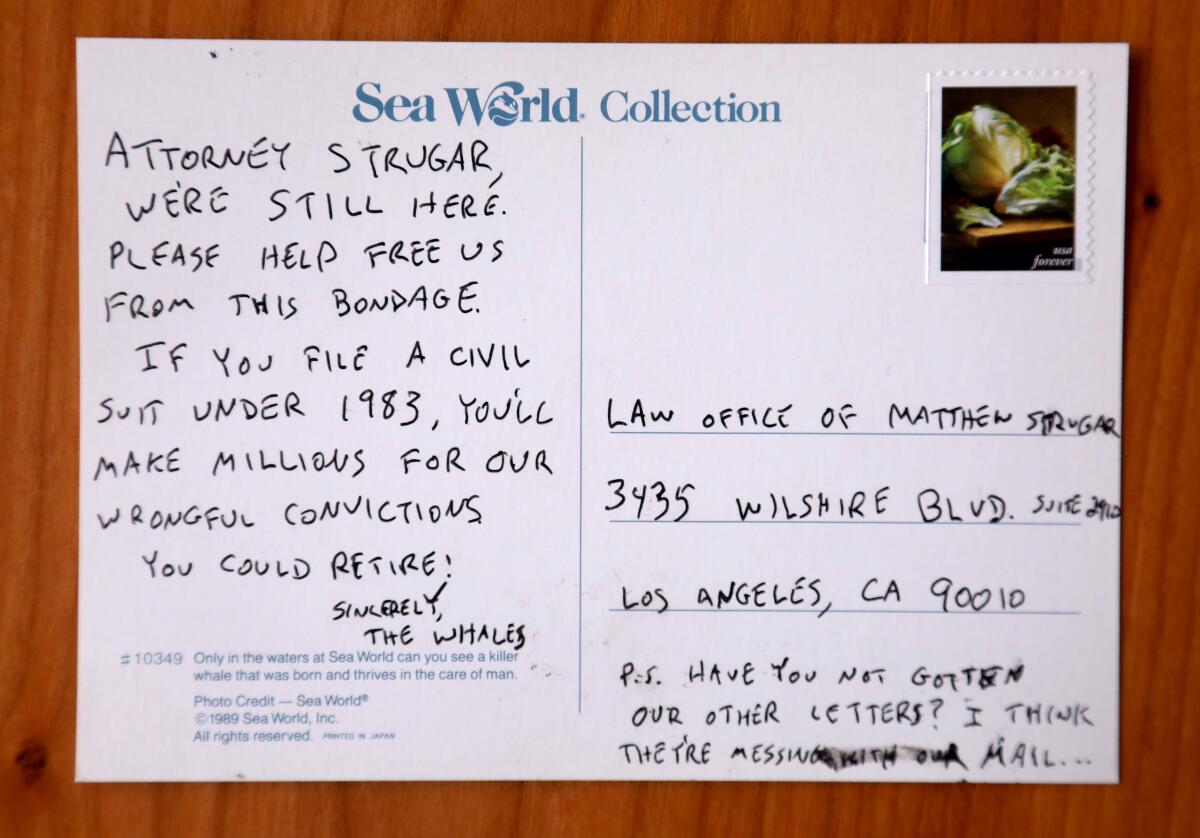

“Attorney Strugar, We’re still here,” read the back of a postcard of two orcas touching noses.

“Please help free us from this bondage. If you file a civil suit under 1983, you’ll make millions for our wrongful convictions. You could retire. Sincerely, the whales. P.S. Have you gotten our other letters? I think they’re messing with our mail.”

“I was pretty excited that he had no idea it was me,” said Thomson. “I felt like that was the big finale, the culmination of a longtime joke, and it was successful both in the moment I was sending [the cards] and in the end.”

But it wasn’t the end.

A few weeks ago, Strugar collected the cards and posted them on Twitter.

The thread went viral, beyond the small online world of “animal liberation, prison abolition, and obscure constitutional litigation” that Thomson expected. For a moment, Thomson was worried. Would there be a backlash? Angry animal rights activists? Accusations he was mocking the incarcerated?

Investors alleged SeaWorld deceived them about the anti-captivity documentary’s effects on park attendance. The settlement still needs court approval.

But people loved the prank. They loved Thomson’s commitment to it, the tenaciousness and wit. Commenters were “elated,” and dubbed it “bananas.” He gained 700 new followers on Twitter.

Thomson suddenly found himself in a virtual spotlight, and felt an unexpected sense of community — that there were others out there with his quirky temperament, his same passions, who got the joke.

It was more than funny, though. It was as if Thomson had become the opposite of the Bad Art Friend from another viral story, one about warring writers who seemed intent on tearing each other down.

Instead, Thomson had lifted Strugar up, quietly, with no other purpose than a bit of distraction for two people in a line of work that is often high-stakes and unrelenting, letting Strugar know that someone out there saw what he did, what he believed in, and valued it.

It made Grace, the red-pen writer, ask, “Who is the star of the prank?”

Grace said Thomson is always “thoughtful about what people in his life may appreciate.” She wondered why so many, especially men, keep their best self only for romantic partners. She thinks maybe we’d be better off “if more people felt more comfortable doing fun and sweet things for friends.”

The postcards resonated, she speculated, because after nearly two years of “terrible, depressing, hard things,” Thomson found a way to keep his lightheartedness intact. He gave Strugar a bright spot, and Strugar gave it to the rest of us.

And that gave Strugar the final reveal, unmasking Thomson as clever and bighearted, an undercover agent of merry mischief — the hard-charging, punk rock P.I. who can remind you with a postcard from a whale that life’s not so bad.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.