Omicron variant adds new peril to holiday season in California and beyond

- Share via

A newly identified coronavirus variant that has sparked global restrictions on travel and shaken financial markets could make the critical holiday season even more perilous in California and across the nation.

Even before the Omicron variant was discovered, health officials were warning of a winter wave of COVID-19 as society regroups for holiday events and travel, and cold weather keeps more people indoors. While it’s not clear how dangerous the new variant is, it’s adding urgency to efforts to get more people vaccinated — and to get booster shots for those with waning immunity — and to follow masking and other safety rules, experts say.

“The new variant adds another reminder that there are more new variants out there that are potentially incubating,” said Dr. Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute in La Jolla. “So if anything, the silver lining of Omicron is it’s a wakeup call for all those people thinking we’re at the end of this. No, we’re not — not by any stretch, unfortunately.”

While no cases of the Omicron variant have been detected in the United States, many experts say it may already be here, given the country’s lack of systematic genomic sequencing that would flag it.

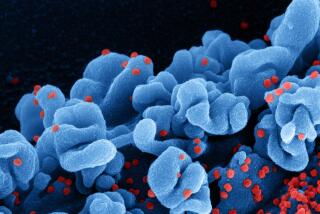

The variant, first identified in South Africa amid a spike in infections there, has more mutations than any scientists have seen, including some that may make the virus more resistant to immunity generated from previous infections or vaccines. But much isn’t known, including whether the variant is more transmissible, results in more severe illness or reduces the efficacy of vaccines.

“We are in a constant battle with this virus,” said Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, chair of UC San Francisco’s Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics. “We have to always be vigilant, and we neither have to overreact to this or assume that there is no threat at all.”

California will go into December in better shape than many other states. New coronavirus cases in California have decreased slightly in recent weeks after ticking upward in late October. But there continue to be hot spots in California where the Delta variant’s impact on hospitals remains high; in the Central Valley, some hospitals are overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients.

Nearly 64% of Californians are fully vaccinated, according to The Times’ vaccine tracker, but that figure is too low to curb an expected fifth surge of COVID-19 this winter. There has been an uptick in demand for shots among 5- to 11-year-olds, and interest in booster shots is rising, but authorities are concerned about lackluster rates of vaccination among young adults.

The specter of a potentially dangerous new variant comes as many report an overwhelming sense of pandemic fatigue as the health crisis approaches its third year.

While jabs and boosters are offered in the U.S. and much of Europe, vaccination rates remain low in southern Africa, where the Omicron variant was first detected.

The World Health Organization on Friday named the new variant Omicron and quickly classified it as a variant of concern. The news prompted multiple countries, including the U.S., to restrict travel from South Africa and other African nations. The U.S. travel restrictions take effect Monday.

“It clearly has been around for weeks. It has been moving silently. It takes a while for these kinds of things to come to your attention,” said Dr. Robert Schooley, professor of infectious diseases at the UC San Diego School of Medicine.

Still, he said, it is difficult to predict when the variant might pop up in California.

“One of the things that makes it hard is that we may have seen it first in South Africa because they have a more sophisticated system of tracking variants,” he said. There is no evidence that the variant arose there, he added — it could have started anywhere with a connection to that nation.

While restricting travel could have benefits, it’s unlikely to prevent the variant from spreading, he said.

“It will give us more time to understand its properties, to convince people who haven’t been vaccinated that they have a moment to jump on things, but it is not going to prevent it from becoming global,” he said. “We live in a global world.”

The variant has about 50 mutations, Topol said. Of those, 30 are in the spike protein, which is targeted by vaccines and some monoclonal antibody therapies, according to Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, an epidemiologist and infectious-diseases expert at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health.

“So the concern is, will this variant have some ability to work around, if you will, our vaccines and some of our therapies?” Kim-Farley said.

Early observations suggest that could be the case, with breakthrough infections reported in vaccinated people, Topol said.

“We know breakthroughs are occurring, and they have so far occurred with multiple vaccines,” he said. “That is, in and of itself, concerning. And looking at the structure of the virus, it could have the potential to basically override our immune response.”

Initial data suggest that the variant causes mild illness, based on many of the cases followed in South Africa, Topol said. That would make sense from an evolutionary point of view, as it’s advantageous for a virus to become more infectious but less virulent, Kim-Farley said.

“If a virus becomes so severe that it’s killing most people, then it will not travel much, because it needs people that can transmit to others,” he said. “So in a sense, the virus is seeking to increase transmissibility and usually to actually decrease its severity.”

But although scientists can make educated guesses about how the variant behaves based on its genetic structure and initial reports, more testing and observation is needed.

“At the moment, all of these questions really are still up in the air as to the answers, and so that’s why there’s so much intense scrutiny going on in South Africa and countries in Southern Africa, as well as now the fact that it has been seen most recently in the U.K., the Czech Republic and Belgium,” Kim-Farley said. “And so the guard is up everywhere now to be looking for this new variant, because no doubt it will be found in other places.”

The variant has also been found in travelers to Israel and Hong Kong; Germany and Italy reported cases Saturday afternoon.

In people who got a booster shot, levels of neutralizing antibodies exceeded the peak that followed two doses of COVID-19 vaccine.

When it comes to dealing with Omicron, California is well positioned compared to much of the country, because elected officials have largely been in agreement with public health experts on imposing control methods like vaccination and masking requirements, Kim-Farley said.

Even if the variant were to spread and generate a surge in hospital patients here, the healthcare system has had plenty of practice in weathering these types of spikes. That picture may be somewhat more complicated in the Central Valley, where officials are already expecting a difficult winter due to relatively low vaccination rates.

California’s statewide rate of full vaccination is slightly higher than the U.S. average, which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates to be 60%, but the rate remains “well suboptimal,” Topol said.

“We need 90% of people, at least, who are vaccinated or have had a recent COVID infection confirmed, and we’re not even close,” he said, adding that this leaves millions of Californians who need to gain immunity. “We are very vulnerable here, and it can change quickly. Once it gets going, it becomes exponential — we’ve seen this repeatedly, and we haven’t learned that lesson yet.”

He urged people to take extra precautions during holiday gatherings, including testing attendees and hosting events outdoors or, if indoors, with open windows and air filtration devices.

Bibbins-Domingo added that “common sense” tactics include wearing a mask and evaluating whether to enter “riskier travel situations.”

Scientists should also increase the frequency of deep analysis of the results of COVID tests, she said.

“When you go to get a PCR test, for example, right now, your PCR test is just telling you whether the swab you gave has the virus present or not,” she said. “But we can take that same swab and go right down to the pieces of DNA that allow you to characterize that virus down to its molecular level.”

Now that scientists in South Africa have raised the red flag about Omicron, those in the U.S. will likely carry out that more rigorous research with greater frequency, Bibbins-Domingo said.

The most important thing people can do is get vaccinated and get booster shots when they’re eligible, because even if the variant does render vaccines less effective, they offer some protection and remain the best tool to fight the disease, Kim-Farley said. It’s anticipated that manufacturers will be able to rapidly adjust the formulations of vaccines to account for the variant if needed, similar to how the flu shot is adjusted each year, he added.

More than anything, he said, the emergence of the variant has shined a harsh light on exactly what will be needed to bring the pandemic under control: global solidarity.

“We really should think of the world as one human body,” he said. “And if we have a sore on our foot, the brain cannot say, ‘I don’t have to worry about it; it’s only the foot,’ because ultimately, that sore could become infected, and the whole body dies.”

Times staff writer Luke Money contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.