Hallelujah! The remarkable story behind this joyful word

- Share via

It begins with the violins — orderly and baroque. The choir rises. The audience rises. And before you know it, the concert hall, church, rec center or school auditorium fills with the triumphant sound of one of the most beloved musical works of the season: Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus.

Over the next four minutes (and change) the choir will repeat the word hallelujah 48 times, but the audience and musicians never seem to tire of it. Credit Handel’s vibrant melody, but also the almost mystical power of that combination of vowels and consonants.

HalleLUjah!

HalleLUjah!

Hah-lay-ay-loo-YAH!

But what does hallelujah mean, exactly? And why does it continue to resonate with us, untranslated, thousands of years after it first appeared in the Hebrew bible?

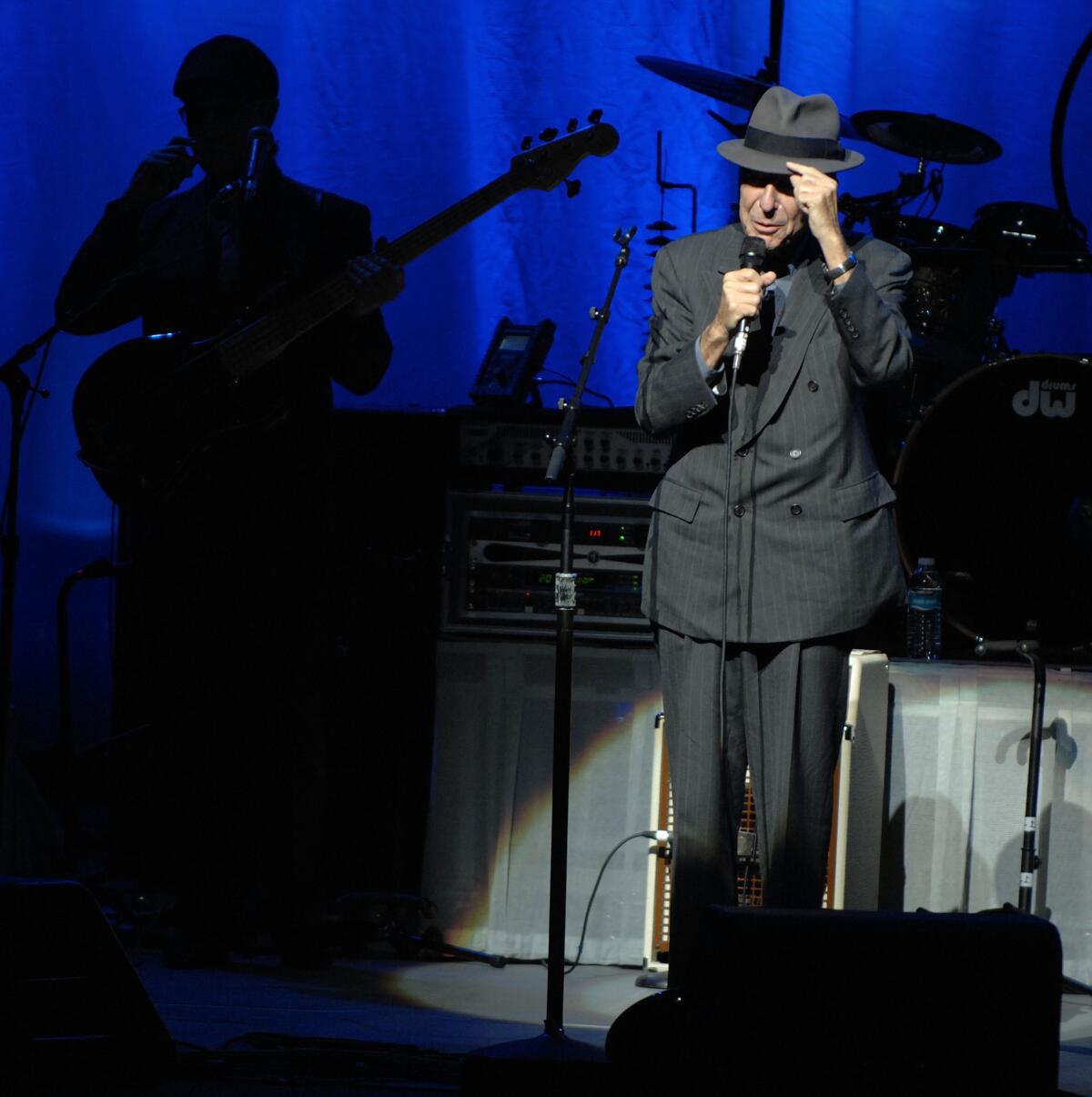

And what is it about hallelujah that inspires composers and songwriters to deploy it so frequently and reverentially from Handel to Ray Charles to Leonard Cohen?

The Oxford English Dictionary defines hallelujah as “a song or shout of praise to God,” but biblical scholars will tell you it’s actually a smash-up of two Hebrew words: “hallel” meaning “to praise” and “jah” meaning Yahweh, or God.

But that’s just the official meaning. For Grant Gershon, director of the Los Angeles Master Chorale, hallelujah is a perfect word because it can take on different meanings.

“It’s this sound that is just so full of possibilities,” he said. “You can fill it with whatever you need to say or communicate.”

In Handel’s great chorus, the word is joyous, victorious, accompanied by trumpets and drums. In Sergei Rachmaninoff’s “All Night Vigil,” however, hallelujah reflects a more quiet devotion. Repeated over and over again, it serves almost as a mantra.

“I imagine an older Russian person in front of an icon, just murmuring to themselves, ‘Hallelujah, hallelujah, hallelujah,’ ” Gershon said.

As a side note, the Russians add an extra vowel sound to their hallelujah and drop the “H” so it is pronounced Ah-lay-lu-ee-yah. That opens up even more possibilities to the liquid, fluid approach to the word, Gershon said.

Hallelujah first appears in the Book of Psalms — a compendium of sacred poems in the Jewish Bible that dates to the 5th or 4th century BC. There it generally prefaces the beginning of a passage or shows up at its conclusion.

“Hallelujah functions as a summary,” said Chris Blumhofer, assistant professor of New Testament at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena. “It’s meant to usher you into the experience of praising who God is and what God’s done.”

Sarah Bunin Benor, director of the Jewish Language Project and a professor at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles, said hearing the word makes her think of the Hallel — a recitation of Psalms 113-118 chanted by observant Jews on holidays.

“We say it on Rosh Hodesh, the first day of the month celebration. It’s part of the Passover Seder,” she said. “It’s a very joyous prayer, very beautiful and very meaningful.”

Hallelujah shows up just four times in the New Testament, all in the Book of Revelation. All four come at the climax of the text, when God delivers his people from the destructive power of Babylon. In response to this deliverance the people cry out, “Hallelujah!”

“They are praising the salvation from oppression and violence,” Blumhofer said. “They are praising God for delivering his promises and protecting his people.”

Scholars can’t say for sure why hallelujah was preserved intact when nearly every other Hebrew word in the Bible was translated first into Greek and then into Latin (amen is another notable exception). Markus Rathey, a professor of early Christian music at Yale University, said it suggests the word was already charged with an emotion that transcended its linguistic meaning.

“I must say, personally, hallelujah sounds so much more beautiful than simply just ‘Praise the Lord,’” Rathey said. “Hallelujah is almost music already, even without a musical setting.”

That musical power comes through no matter the spelling. The Oxford English Dictionary lists eight English transliterations from the Hebrew, including alleluia, allelujah and hallelujiah. There’s even an adjective: hallelujatic.

All those vowels lend themselves to music.

“It’s like the perfect word to sing,” Gershon said. “It has all these long vowels, and all the consonants are liquid as well. It feels like this beautiful flowing stream of sound.”

Historically, the word has offered composers and vocalists the opportunity to use the voice in unusual ways, Rathey said.

“Because it’s only one word and it has that final long ‘ah,’ it inspired composers to write very beautiful, almost instrumental lines that put celebration and the sound of music in the foreground,” he said. “The focus is not on the word anymore; it’s really on playing with sound and virtuosity.”

Thousands of works of classical liturgical music use hallelujah, in part because there was a great need for them. In the first half of the traditional Mass in the Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran traditions, there are two biblical readings separated by several musical pieces. One of them is “Hallelujah.”

“There were ‘Hallelujahs’ that were sung by the congregation, but at a major church it could be an opportunity for a composer to create a larger-scale piece that is performed by a choir,” Rathey said.

Hallelujah was seen as so joyous that it had to be put away for the 40 days of Lent. It was considered too celebratory for such a subdued time of the ecclesiastical year.

There are stories of choir boys in the Renaissance making a tiny coffin and putting the word hallelujah in it, only to resurrect it at Easter.

“Even if you don’t notice that it’s gone, I know the feeling on Easter morning when all of a sudden you are singing it again,” Rathey said. “It’s almost like a beautiful dress that you get out for celebration on Easter morning.” (In fact, Handel’s “Messiah,” composed in 1741, was originally intended for Easter week.)

There is no set time that the word is sung (or not sung) in the nondenominational church that Deborah Smith Pollard attends in Michigan, but she said it shows up when the spirit, emotion and joy begin to crescendo.

“When the praises are so high, somebody is saying hallelujah,” said the professor who studies gospel music at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. “Maybe it’s pastor, or maybe it’s somebody in the choir singing it. All of a sudden, you might see members of the audience singing or saying hallelujah.”

Smith Pollard also sees the word being used outside the church. She is also a radio host, and for the last two years she’s hosted an annual gospel concert and fundraiser put on by DTE Energy, which provides heat for many people in the Detroit area. The event is called “Hallelujah for Heat.”

Smith Pollard thought it was a cute name for when she first heard it. Then her furnace broke down in a cold Detroit winter.

“When we got it working again, the first thing I said was, ‘Hallelujah!’” she said. “You immediately go: Praise God, I’ve got heat again!”

“You don’t have to be in the church, or a Christian, or tied to the Jewish community to use that word,” she said. “Hallelujah shows up in the community.”

It shows up in Ray Charles’ “Hallelujah I Love Her So,” where the singer uses it to implicitly thank the divine for bringing the woman next door into his life. Hip-hop artists like Chief Keef and Logic have titled songs “Hallelujah” as they celebrate their own success. Recently, the L.A.-based band Haim released a Fleetwood Mac-inspired song in which the word serves as a way to acknowledge the blessing of having friends and family help them through life’s challenges.

But by far the most popular and famous use of hallelujah in popular music is Leonard Cohen’s haunting and frequently covered “Hallelujah,” written in 1984.

The song does not rely on biblical quotations, but it does make use of biblical stories: It’s about David, who consorts with Bathsheba, and orchestrates her husband’s death so he can marry her. And it’s about Samson, who, instead of saving his people from a hostile army, runs off with Delilah, who cuts his hair, leaving him powerless.

But ultimately, the song is about all of us — our failings, our imperfections, and our desire to have a relationship with the unknowable divine, said Marcia Pally, author of “From This Broken Hill: God, Sex and Politics in the Work of Leonard Cohen.”

“He articulates in the song what we know about ourselves,” she said. “It’s about our relationship with the transcendent and with other people, how we breach those relationships, and sever them, and yet still we have to come back to hallelujah.”

Amen. (But that’s another story.)

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.