- Share via

Two days after Kobe Bryant was killed in a helicopter crash, a young man with a shaved head and muscular, tattooed arms walked into a Norwalk bar and took a seat at the counter. His name was Joey Cruz, a deputy trainee at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

Cruz, who had been on patrol just two months, had stood sentry at a trailhead leading to the debris field in the hills above Calabasas in the frenzied aftermath of the crash. People had swarmed to the area — reporters and devastated fans, lookie-loos and seekers of macabre souvenirs — and Cruz had helped keep them away.

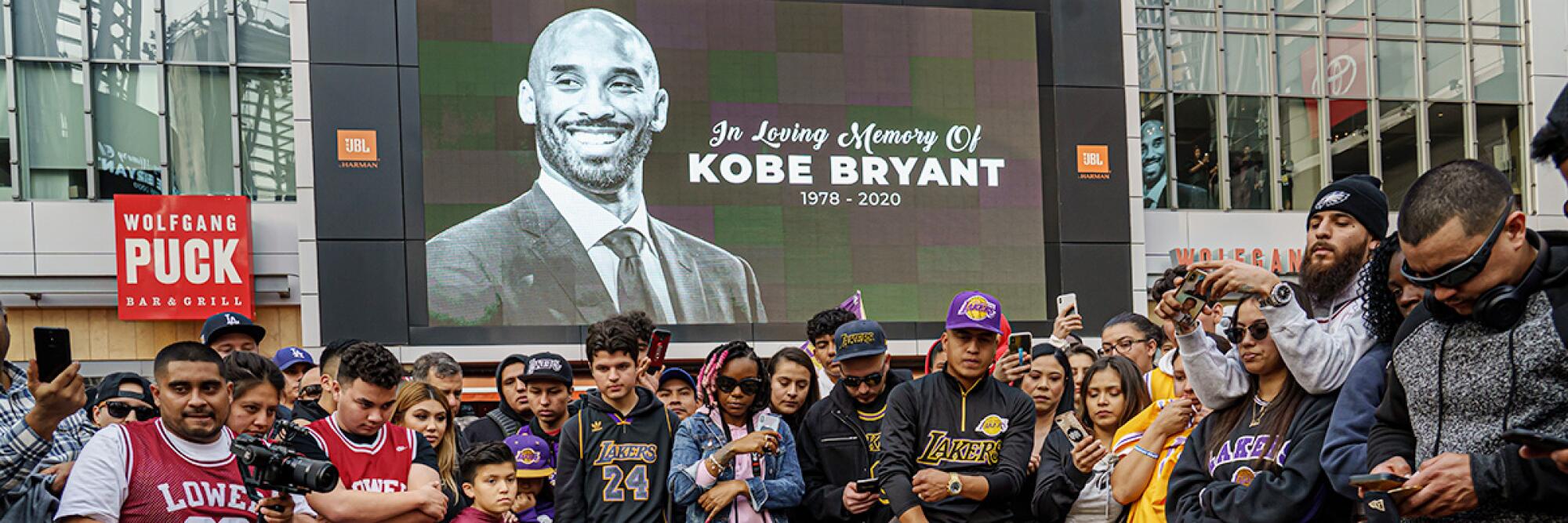

Now Cruz sat at the Baja California Bar and Grill 45 miles south, a bottle in his left hand and his phone in his right. Across the world, news and social media were full of tributes to the basketball great, and questions about the Sunday morning crash that killed him, his 13-year-old daughter, Gianna, and seven others.

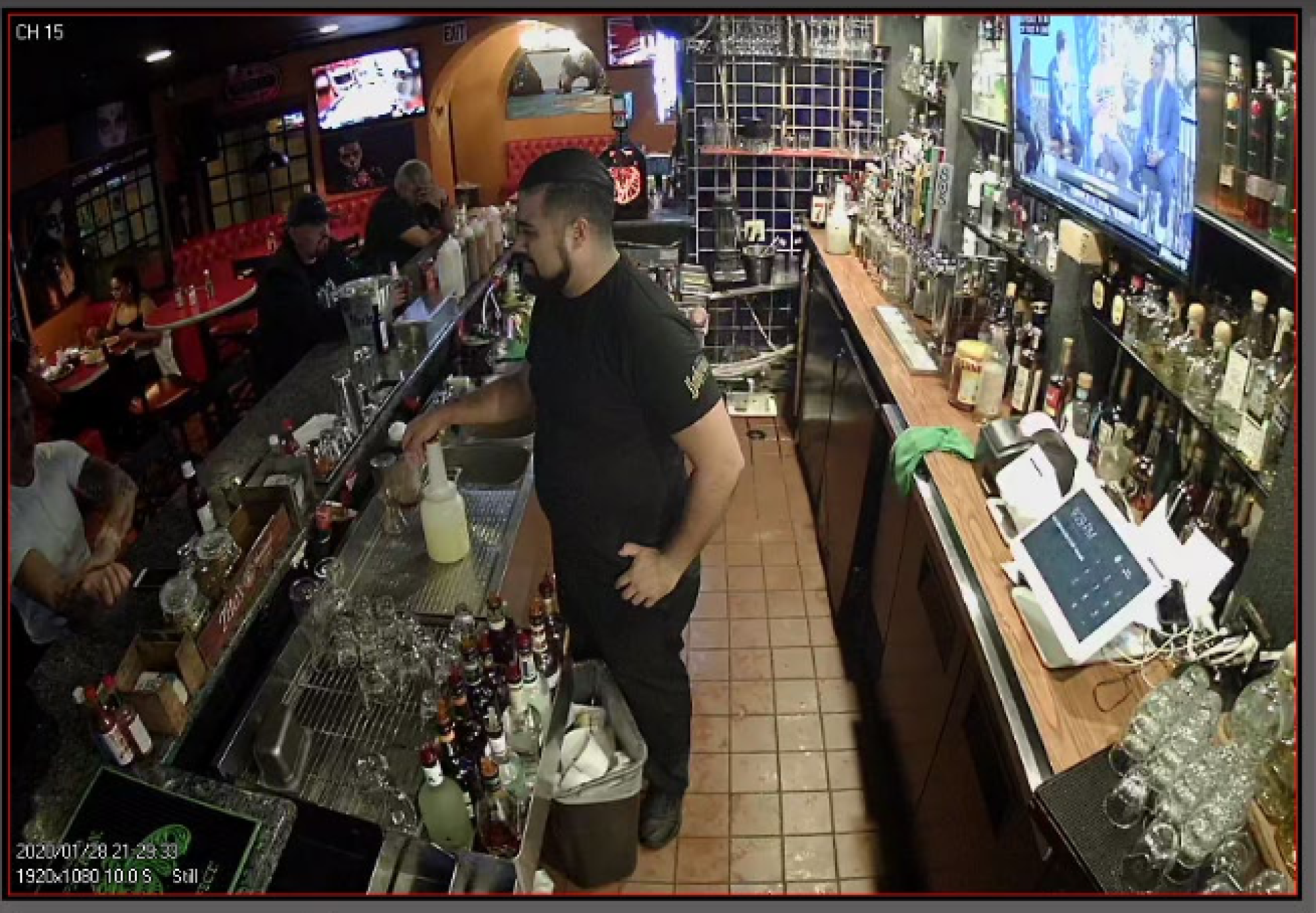

Cruz had photos of the carnage on his phone, forwarded to him by another deputy. About 9:30 that Tuesday night, bar surveillance footage captured him showing his phone to the bartender. Cruz appeared to make a downward slashing motion with his arm, as if to indicate the nature of the injuries on display.

In a nearby booth sat Ralph Mendez, a 46-year-old real estate investor. He was there with buddies from his softball league. They did not hear the conversation. But soon the bartender came over to explain that the muscular man who had just left was a deputy, and had shown him photos of Bryant’s remains.

Mendez’s friends did not really believe it — it sounded like empty bar talk. The muscular man was probably not even a deputy. But Mendez thought it might be true. He’d seen a Marine Corps tattoo on the man’s arm, which fit his image of a cop.

The case between Vanessa Bryant and L.A. County has intensified in recent weeks, with Bryant detailing her interactions with Sheriff Alex Villanueva.

Driving home, Mendez brooded about what to do. If it was true, and the grisly photos got out, he would regret not trying to stop it. He admired Kobe Bryant and had wept at the news of his death. He had watched the Lakers play all his life, but the connection he felt to Bryant really took hold after the star’s 2016 retirement. He would see Bryant courtside beside Gianna, smiling.

Mendez’s fiancee, at that moment, was pregnant with a girl, after an excruciating eight-year gantlet of fertility doctors. And when Mendez thought of becoming a father, he saw a model in Bryant, a dad who brought his daughter everywhere.

All of that, Mendez will say, played a role in what he did next. When he got home to Cerritos, he sat in his driveway and took out his phone. He went to the sheriff’s office website. He found the Contact Us link, and wrote:

There was a deputy at Baja California Bar and Grill in Norwalk who was at the Kobe Bryant crash site showing pictures of his ... body. He was working the day the helicopter went down … He is a young deputy, shaved head with tattoos on his arm …

He hesitated, then hit “submit.” It was 12:21 a.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 29. The email soon reached Sheriff Alex Villanueva, who quickly offered deputies amnesty from discipline if they came clean and deleted the photos.

Complete coverage of the death of Kobe Bryant, his daughter, Gianna, and seven others in a helicopter crash.

The sheriff insists he did the right thing, that his strategy was a success. The families of the victims never saw the grisly photos. Nearly two years have passed since the crash, and the images never hit the internet.

The possibility that they might surface, however, underpins the lawsuit by Bryant’s widow now being fought in federal court. “For the rest of my life, one of two things will happen: either close-up photos of my husband’s and daughter’s bodies will go viral online, or I will continue to live in fear of that happening,” Vanessa Bryant said in a declaration in the case.

Bryant, and other families who lost loved ones in the crash, sued the county and the sheriff for negligence and invasion of privacy. The Board of Supervisors has already agreed to pay $2.5 million to settle two of the suits. But Bryant and one other family have refused to settle.

Lawyers for the county have demanded, and won, access to Bryant’s psychological records, in hopes of showing her anguish is independent of the photos. The lawyers have called her suit a vengeance-fueled “cash grab” of taxpayer dollars by a plaintiff who is already a millionaire many times over, and whose legal argument depends on “hypothetical harm.”

The scandal surrounding the photos has already prompted a change in the law, making it a misdemeanor for first responders to take unauthorized photos of a death scene, a law the sheriff supported. In her deposition in the case, Bryant insisted she still wants “accountability,” but did not specify what that means.

Bryant’s lawyers argue that the images spread to at least 28 sheriff’s deputies and a dozen firefighters. Because many of the people who possessed the images deleted them, reset their phones or swapped them for new phones, the attorneys say, it is now impossible to tell how far the photos spread.

The court will consider the case in the light of a 2012 ruling from the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals that involves the death of a 2-year-old boy. In that case, a former prosecutor gave images of the boy’s corpse to journalists, prompting a lawsuit by the mother, Brenda Marsh, who argued she was horrified at the possibility of finding her son’s death images on the internet.

“We find the Constitution protects a parent’s right to control the physical remains, memory and images of a deceased child against unwarranted public exploitation by the government,” the court ruled. The case “shocked the conscience,” the court said, finding that the dead child’s mother might easily stumble across the photos on the internet.

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

In the Bryant case, the county acknowledges that Deputy Joey Cruz flashed his cellphone at the Norwalk bar, and that a fire captain displayed crash photos to colleagues at a hotel banquet. But county lawyers argue the photos were never “publicly disseminated.” In contrast to the Marsh case, the lawyers point out, not even the media got them.

“The subject photos are gone and cannot be recovered,” county attorneys argued in a recent motion asking for a judge to throw out the case. “This news should come as a relief to plaintiff. Instead, she continues to litigate this case with speculation and conjecture.”

Villanueva himself was initially a defendant, but a U.S. District Court judge dismissed him from the case in December, saying it “defied common sense” that his instruction to delete the photos would somehow increase the risk of their dissemination. If the remaining case survives L.A. County’s effort to throw it out, it is scheduled to go to trial in early 2022.

::

Hours after the crash, Vanessa Bryant walked anxiously into the sheriff’s Lost Hills station in Calabasas to meet Villanueva face-to-face. The crash was dominating the news, and the phrase “RIP Kobe” kept appearing on her phone, but one of her assistants had said there were rumors of survivors.

Leaving from Orange County, Bryant had traveled by car nearly two hours to reach Lost Hills. By her account, she was shuffled from room to room while she waited to meet the sheriff. She was ushered to a closet-sized room with kids’ toys. Then to a conference room. Then back to the first room.

She kept asking whether her husband and daughter were OK, but could not get an answer. Finally the sheriff appeared and told her there had been no survivors. As Villanueva would recall, Bryant expressed worry about paparazzi swarming the crash site, and he promised to secure the area and keep lookie-loos out.

The way Bryant remembers it, she testified in a deposition, she made a specific request to the sheriff: If you can’t bring my husband and baby back, please make sure no one takes photographs of them. Get on the phone now, she pressed him, to secure the area.

Villanueva left and came back, she recalled at the deposition, with the promise that the area was secure. But soon afterward, gruesome photos of the crash were being texted and AirDropped among his deputies.

Firefighters also got ahold of photos, and about three weeks after the crash, Tony Imbrenda, a captain and spokesman with the L.A. County Fire Department, was at the Golden Mike Awards ceremony recognizing radio and TV journalists at the Hilton Hotel in Universal City.

During the cocktail hour, Imbrenda showed off his photos of the crash to some firefighters, in proximity to their spouses. A firefighter’s wife complained, according to internal Fire Department records filed in court. Around the time that reports of photo sharing emerged, Imbrenda deleted about 45 photos and instructed eight to 10 others to do the same, he said in a deposition.

::

Soon after Mendez sent his email complaining about what had happened in the Baja California Bar and Grill, then-Capt. Jorge Valdez, head of the sheriff’s information bureau, began looking into it. He interviewed Mendez and showed up at the Norwalk bar to collect surveillance footage, which showed the deputy trainee, Cruz, flashing his phone to the bartender.

As Villanueva tried to contain the damage, he would later say that he thought of the infamous case of 18-year-old Nicole Catsouras. After she was killed in a car crash in Orange County in 2006, California Highway Patrol officers leaked gruesome photos that proliferated on the internet. Strangers mocked the family online. The CHP agreed to pay $2.4 million to settle her family’s lawsuit.

Villanueva did not want a repeat of that. “That’s just mind-boggling,” he said. “And I did not want anyone to ever have to go through that again.”

The sheriff made it clear that he did not want the photos to see the light of day, and his subordinates, Valdez and then-Lt. John Satterfield, handed down orders that the deputies delete them.

One by one, deputies were called in and told that they could avoid discipline if they came clean and erased the photos from their phones. Some deputies opened their cameras for review, but sheriff’s officials did not actually scour the phones to ensure the photos had not been shared by text or on social media or saved to iCloud, according to depositions.

By the end of the week, the deputies known to have the photos submitted memos attesting that they had been deleted. No one was disciplined.

The sheriff’s strategy troubled Capt. Matt Vander Horck, who ran the Lost Hills station. He knew that a prior sheriff had gone to prison for thwarting a federal investigation. What if the photos had evidentiary value? Was the department breaking the law, somehow, by deleting them?

Vander Horck testified that he made his concerns known, but he was ignored. He was soon moved, for what the sheriff said was his mishandling of an unrelated case.

‘If I had to do it all over again, I’d probably make the exact same decision,’ sheriff testifies in Vanessa Bryant’s lawsuit against the L.A. County.

Bryant says the Sheriff’s Department mishandled the investigation so she will never know whether there are still photos out there. In a court declaration, she wrote: “My fear and anxiety is informed by my understanding that the Sheriff’s and Fire Departments did not preserve or meaningfully search the wrongdoers’ phones. Because of that, I do not believe all copies of the photos have been secured.”

::

On Feb. 26, nearly a month after the crash, and weeks after the sheriff’s brass became aware of the problem, The Times asked sheriff’s officials about the complaint from the Norwalk bar.

Valdez and Satterfield — who together had gone to the bar to pick up the surveillance video and had executed the sheriff’s photo-deletion plan — denied knowing about such a complaint.

“We’re such a large organization — I mean, if there is, it hasn’t come down to our office,” Valdez told The Times that day, a remark captured in an audio recording. “I’m unaware of any complaint.”

Pressed further, Valdez said: “There was no order given to delete any photographs. I’m not aware of any complaint.” He looked toward Satterfield. “Are you aware of any complaint?”

“I’m not aware of any complaint,” Satterfield said.

- Share via

Then-Capt. Jorge Valdez and then-Lt. John Satterfield said they were unaware of a complaint about a deputy showing crash photos to a bartender in Norwalk.

Since then, the sheriff has promoted both Valdez and Satterfield. They are among his closest advisors.

Satterfield, now a captain, said last week that Mendez’s email was not “a formal ‘complaint.’” Instead, he described it as “an informational observation from a citizen who had been in a Norwalk bar.”

In a recent deposition, Villanueva insisted that the photo sharing was under investigation at the time The Times began asking questions.

The Times published its first story on the photo scandal on Feb. 27. It was not until the next day that the Sheriff’s Department requested an internal affairs investigation, according to internal sheriff’s documents attached to a court filing.

Cruz, who showed the photos at the Norwalk bar, was issued a 10-day suspension as a result of the internal affairs investigation. He appealed, and the department ultimately gave him two days off without pay, plus three days of classes, he said in a deposition.

“I made a bad decision,” Cruz said in the deposition. “I made a decision that, if I could go back, I would change the whole outcome.”

L.A. Sheriff’s Department says it is looking into reports that deputies shared graphic images of the Kobe Bryant helicopter crash scene.

Mendez, whose email to the Sheriff’s Department set the case in motion, said it has been uncomfortable to watch it unfold. The softball buddies who had been with him that night did not want to get involved, and he was hesitant to tell them he had complained. When he finally told them, he said, they assured him he had done the right thing. He said he does not regret it.

“I’d do it again in a heartbeat,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.