After a Black student faced racist slurs, some wonder: Will O.C. ever change?

- Share via

Watching his son play basketball at Laguna Hills High School, Terrell Brown couldn’t shake an uneasy feeling.

He has felt it before in Orange County, where he and his family are often the only Black people in a room.

For the record:

11:38 a.m. Feb. 8, 2022An earlier version of this article said the Laguna Hills High mascot is the Eagles. It is the Hawks.

Fans of the home team, the Hawks, and the visiting Portola High Bulldogs slammed their feet against the wood bleachers and screamed. It was a type of energy that often makes for an exciting game. But the vibe was off, Brown recalled.

He was soon proved right. His son, Makai, became the target of racial slurs shouted from the stands by a Laguna Hills student.

A video capturing the slurs at the Jan. 21 basketball game has generated widespread outrage. The family was interviewed by Don Lemon on CNN. A group of local businessmen gave Makai a $20,000 college scholarship.

But Brown and others are wondering what will change in a county where racial taunts of students of color, particularly at sporting events, still happen with alarming regularity.

Brown, who moved to Irvine from the Atlanta area about four years ago, said the overt racism of the South is in some ways easier to deal with than Orange County racism.

The mother of a Portola High School basketball player posted the video to Instagram, saying her family was “up in arms.”

“The microaggressions here are worse,” said Brown, 48. “The guy with the Confederate flag, he’s letting you know he’s a racist. He’s making it very clear. But here, you don’t even know.”

For Black people, life in Orange County can be particularly challenging. They are 2% of the population in a county where whites are a minority and two-thirds of residents are Latino or Asian.

With all the crowd noise, the Browns didn’t hear the insults at the time. Makai, 17, a senior point guard at Portola High, discovered them the next day while studying game footage.

“Where’s his … slave owner? Who let him out of his chains? Who let him out of his cage? He’s a monkey!” the student yelled as Makai shot free throws.

Violence and hate incidents directed at Asian Americans have surged across California since the pandemic, with some blaming Asians because of the coronavirus’ origins in Wuhan, China.

For several days, the Browns dealt with their shock and pain mostly alone.

Then, Makai’s mother, Sabrina Brown, posted the video on Instagram. It was viewed more than 171,000 times in just over a week.

“Laguna Hills Boys Basketball fosters a culture of aggression, unsportsmanlike conduct and RACISM! And this has to be brought to the light and stopped,” Sabrina Brown wrote on Instagram.

The student who yelled the slurs was counseled and disciplined. But some say that administrators at Laguna Hills High have a history of not taking such incidents seriously.

Everyone who attended Saturday’s basketball game between the Coronado High Islanders and Orange Glen High Patriots knew it was going to be a classic, the kind of matchup prep dreams are made of. What wasn’t expected were the flying tortillas.

Brian Hosokawa, 39, president of the Portola High girl’s basketball booster club, posted footage of the incident on YouTube and began forwarding it a day before Sabrina Brown went public with it on Instagram.

Laguna Hills High administrators requested that he take it down.

The video “will only complicate matters for them in their investigation and subsequent disciplinary action,” Portola High Principal John Pehrson wrote in an email, relaying the request to Hosokawa. “They are afraid that this video could distract from other things they are trying to get done as they go through a process to improve things and deal with individuals.”

Hosokawa refused. People need to know what happened if similar incidents are to be prevented, he said.

“As a country, we have allowed racist incidents to be handled quietly for far too long,” said Hosokawa, whose maternal grandparents were among the Japanese Americans unjustly sent to incarceration camps by the U.S. government during World War II. “Their response right away when they found out the video was posted was to try to bury it. That’s part of the toxicity of the culture. That’s why these things keep happening. For every one of these incidents that gets caught on camera, there’s thousands that don’t.”

Laguna Hills High Principal Bill Hinds did not return a call seeking comment.

Last May, at a volleyball game at Laguna Hills High, another Black athlete was heckled with racist slurs by a student spectator.

The student yelled for Jonathan Coleman, a Black outside hitter for Burbank High, to “go back to the plantation” and called him the N-word and a “cotton picker,” said Coleman’s mother, Lorri Hubert.

Officials at Laguna Hills High vowed to investigate. Ultimately, according to Hubert, they said students who were interviewed after the game denied making the remarks.

No one from Laguna Hills High ever called to apologize, Hubert said.

In recent years, students have expressed antisemitic, anti-Black, anti-Latino and anti-gay sentiments at other Orange County high schools including Newport Beach, Costa Mesa, Newport Harbor and San Clemente.

Hubert said listening to Sabrina Brown talk about what happened to Makai put her right back in that gym.

The fallout over allegations of racism at a recent Orange County high school football game erupted on social media over the weekend, reflecting the broader tension gripping the country in the Trump era.

“I cried when I heard it. I didn’t sleep the entire night because I had chills through my body,” she said. “Some of the same exact language that was spoken to her son was said to my son. And now they’re sorry? This could have been prevented.”

State Sen. Dave Min (D-Irvine) said Orange County has come a long way from its past as a bastion of white conservatism.

Incidents like these are a throwback as the county grows increasingly diverse and progressive, he said.

“I wouldn’t be elected if that was still Orange County,” said Min, who is Korean American. “The county is changing, but unfortunately, we still see sentiments of that old, ugly specter of hate that rears its head every once in a while. But we’re not going back.”

To change a culture that enables racist behavior, school leaders need to educate students on how to respond, rather than just punishing the perpetrators, said Peter Levi, regional director of the Anti-Defamation League.

“It’s about the greater environment,” Levi said. “This person was yelling racist obscenities throughout the game, but what were the people around the individual saying? Were they doing nothing or joining in? There’s a greater culture on these campuses that needs to evolve.”

After the student unleashed his racial invective at the Laguna Hills High basketball game last month, another student responded, “You always say the wildest s—, bruh.”

In addition to disciplining the student who hurled the slurs, school officials advised students who witnessed the incident on their responsibility to “redirect such language” and immediately report it to administrators.

They have also discussed how to make changes with players, coaches and student government representatives.

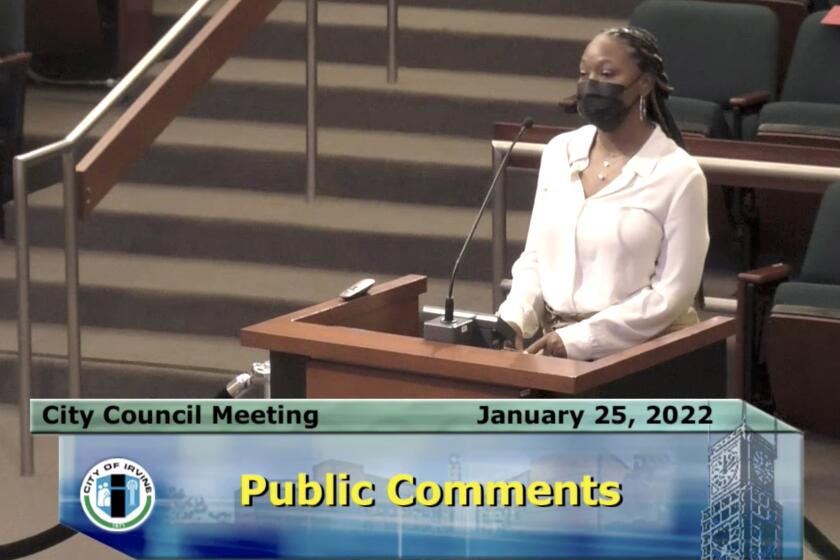

For Irvine Mayor Farrah Khan, that is not enough. She has received numerous complaints about the sports culture at Saddleback Valley Unified School District, which includes Laguna Hills High.

“I am asking SVUSD to conduct an investigation into the coach and other staff regarding their involvement in incidents like this and bring forward appropriate actions taken,” Khan said in a letter to the school district and Laguna Hills City Council.

When Terrell Brown left Atlanta, his work as a regional director of a tax preparation company allowed him to settle almost anywhere in California.

Sabrina Brown, 44, a registered nurse, chose Irvine because of its high-achieving schools.

Their friends in Atlanta — a city with a large Black middle class — were in disbelief. Some said they would never let their kids go to school in Orange County because of a history of racism against Black people.

But the Browns forged ahead because of their emphasis on the best education for Makai and his younger sister.

Makai Brown wants to study sports psychology at UCLA.

At Portola High, where he also plays baseball, most of his teammates are Asian, but there are also two other Black players. He loves the high school, which he says is the “best in Irvine” — and one where classmates and teachers treat everyone with respect.

“When I first watched the video, it was an initial shock,” he said. “After a little bit, it wasn’t really that surprising anymore. You shouldn’t say those things anyway, but the fact he said them at a game out loud and in front of a camera and no one said anything — none of it makes sense to me.”

A week after the game at Laguna Hills, Makai arrived at Portola High for the last home game of the regular season against Irvine High.

It was senior night, when soon-to-be graduating players and their families are honored.

Under an arch of purple and silver balloons, Makai stood next to his parents and sister as he was presented with a courage award — a $1,000 check from a local business.

A group of local businessmen surprised him with a $20,000 college scholarship, an internship with a sports agent and one-on-one basketball training.

“I couldn’t allow that to be Makai’s last basketball experience, so I called in my super friends to change the narrative,” said JJ Jones, a businessman and mentor in Orange County.

At first, Makai didn’t think that releasing the video would make a difference.

But the support he has received from teammates, classmates and community members has made him think that change might be possible.

“I’m starting to understand that how we’re handling this, putting it out there, maybe it can help other people or at least inspire people not to just sit back and let this happen without doing something about it,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.