In O.C, the wail of a siren on an iPhone app alerts a family when Ukrainian relatives under attack

- Share via

The wail of the air raid siren sent her into a panic. For days, it blared through her duplex in Huntington Beach, a phone alert that signaled her hometown in Ukraine was getting bombed.

Ganna Hovey felt helpless thinking about her parents huddled in the dark basement of their apartment building 6,000 miles away, praying to make it through the night.

The ominous siren made her 7-year-old son run from his room, covering his ears. The family dog barked while their three parakeets hopped around in their cage.

Hovey turned the alert off and wrote a text to her parents: Are you OK?

No response.

It was a windy Saturday in Southern California, palm trees swaying outside her patio door. It was Day 9 of the Russian invasion, but it could be any day of the last two weeks, when her life became an agonizing loop, circling around an app that has become both savior and nightmare.

The Times’ Marcus Yam, no stranger to war photography, gives a first-person account from Ukraine.

The conflict half a world away has changed the lives of the roughly 112,000 people of Ukrainian descent in California. Like Hovey, many feel an overwhelming sense of despair and powerlessness. They’ve donated money, collected supplies to ship back home and participated in protests to call on world leaders to do more to stop Russia. But these acts feel paltry compared with the magnitude of what’s happening in their homeland.

Hovey, 37, constantly watched Ukrainian news. She checked social media and logged into chatrooms to get any information she could about the situation in Kharkiv, the second largest city, under constant bombardment just 20 miles from the Russian border.

She trembled as she stared at the phone, waiting to hear back from her parents. Her son, Leonardo, walked up from behind and wrapped his arm around to comfort her.

The rocket warning app, called Alarm and developed for Ukrainian citizens, plunged her into a minute-by-minute anguish of war that only amplified her sense of paralysis.

The alerts blared when she was working, cooking, dropping her son off at school, sleeping.

“It’s agony,” she said. “When I hear them, I’m thinking what’s happening right now? What building did it hit?”

The sirens had stolen days of sleep. She’d been late dropping off Leonardo at school sometimes. His teachers noticed and told her counselors were available for him if he needed them.

“He’s a resilient boy,” she said “He’s too young and doesn’t understand the situation.”

Hovey knew her phone was a blessing and a curse: She was able to stay connected with her parents in a way war-torn families never have been able to. But it was torture when they didn’t reply immediately.

She prayed and imagined God placing a shield over her parent’s home.

“I repeat a mantra,” she said. “I say: Please don’t hit their home, please don’t hit their home.”

Although her parents appreciated their daughter’s vigilance, the messages and phone calls could be distracting, particularly when they were running down from their third-floor apartment to the basement. Hovey said her mom had asked her to be patient and wait until they were settled in that hovel-like shelter.

“That’s what she asked me to do, but I don’t do that,” she said. “I’m trying, but it’s really hard. A couple of times they did not hear the alarm.”

Hovey said some of the loud speakers warning Ukrainians of possible missile and airstrikes were damaged. Although many Ukrainians had downloaded rocket warning apps, the notifications didn’t always get through. On two occasions, Hovey was the first to alert her parents of an imminent attack.

Almost 800,000 Ukrainians have fled to Poland as Russian forces push farther into Ukraine.

“I told them to hide, run,” she said. “And when they did, my mom told me: You’re our guardian angel.”

On this Saturday, two minutes had passed since she sent the text. Still nothing. She opened up the app.

“It just says: ‘Kharkiv, air alarm. Everyone hide,’” she said.

The alerts had given her a grim education about living in war.

“If it says airplanes, it means it’s bad, you have to hide really deep,” she said. “If it’s just missile or explosion, it means they’re using small missiles. If you hide behind two walls away from glass, you will be OK.”

She had been planning to FaceTime her parents this morning, but that would have to wait.

Hovey looked over videos and photos in her phone displayed on the television screen: her parents inside the dark basement, screenshots of crumbled buildings around Kharkiv. She wondered what fixtures of her childhood were turned to rubble. The elementary school that sits about a block away from her parents’ home? The Lysenko Music and Drama School, where she sang in the choir and learned to play the piano?

She used to take the subway to her university, where she majored in human resources. Now the tunnels have become bomb shelters where some of her cousins have been staying. Two friends with a 1-year-old baby have been sheltering in the railway carriages.

Hovey had left Kharkiv when she was 21. She came to the U.S. after meeting her future husband online. In 2015, she became a U.S. citizen, just a year after giving birth to her son, Leonardo. The couple eventually divorced.

Last year, Hovey petitioned for her parents to get green cards. Her mother, Svitlana Usenko, 57, loved California and came to visit every summer; last year, they went to Catalina for a day. Hovey said her petition was approved in November and the next step was for her parents to be interviewed at the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine.

Her parents were planning to sell three properties and use the money to buy a house in the U.S. so they could all live together. But those properties have now been damaged or destroyed.

“My mom is afraid to come here empty-handed,” she said. “I said: I don’t care, come here alive. That’s all I want. I’ll work three jobs if I have to. I’ll take care of you.”

She added: “I tell them, when it’s safe to leave, go to Poland. I’ll figure out how to get you here.”

Usenko said she would head for the border the second she could. She had a heart problem and feared running out of medication during a long siege. But Kharkiv was under such heavy attack that it was hard to get out.

Hovey was unable to stop crying. The sirens had her constantly on edge.

“I just want my parents here,” she said. “I want Leo to have a family.

“My dad was going to show Leo how to fish and fix things,” she added.

To take her mind off the alerts, she showed a reporter a video of her parents on her phone, taken during the first three days of the invasion. Her father, Oleksandr Usenko, 65, sits on a cot in the hallway outside their apartment.

“This is how we live,” says her mother, a beauty salon owner, speaking in a mix of Russian and Ukrainian. “That’s our bed.”

The cot is so small they were taking turns sleeping. With food scarce, they mostly ate cereal.

Oleksandr Usenko, a retired electrical engineer, speaks to the camera.

“They’re bombing us all the time,” he says.

“Every 30 minutes,” his wife chimes in on the video. “There are sirens all time.”

After three minutes, Hovey realized her mother had responded

to her text with a single word: OK.

“Sometimes that’s all she says. She doesn’t have time to respond,” Hovey said.

The short responses hint at the intensity of the war in Kharkiv. Power outages mean her parents must conserve power. They also fear that Russian forces could use their cellphones to pinpoint their location and target them.

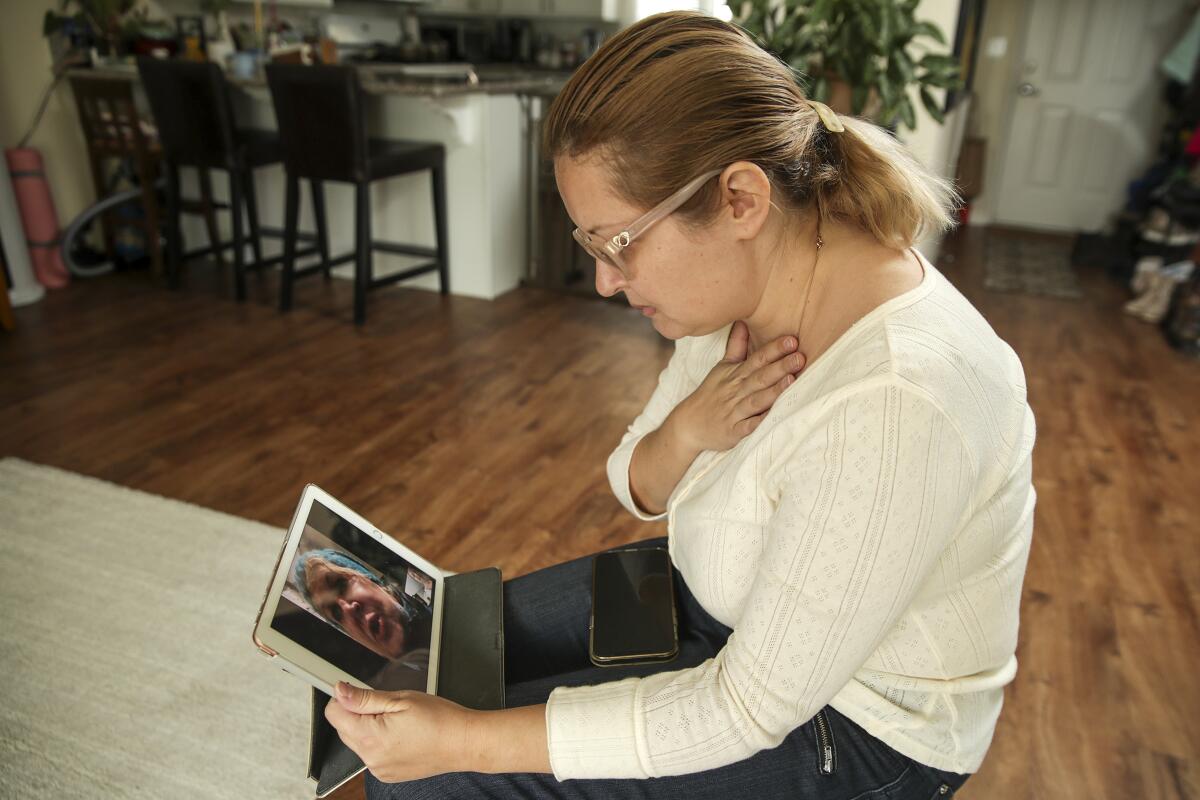

Half an hour later, Hovey was able to get through to her mom on FaceTime. The video took a few seconds to load, then opened to her father sitting on a chair near a stairwell. He waved. Her mom panned the cellphone camera to show other people sleeping in the basement.

Her parents kept the conversation short and told her to tell Americans they want a no-fly zone over Ukraine.

“Close the sky,” Hovey said, interpreting for a reporter. “All we need is close the sky.”

They blew kisses back and forth and hung up.

The parakeets were still. The family dog was waiting to be let out into the porch. Hovey slid the glass door open for him as Leonardo walked over to hug her again. The phone was quiet.

“I just talked to Baba,” she told him. “She’s OK, for now.”

Two days later, Hovey learned that her mom had set out for the Polish border. Her cellphone had died, and Hovey could not reach her until Thursday night, when she learned her mom was at the Warsaw Chopin Airport. Hovey wasted no time and purchased her plane ticket to Los Angeles. Her father decided to stay to help their extended family.

On Friday, Hovey and her son waited for her inside the Tom Bradley terminal at Los Angeles International Airport.

“Baba! Baba!” Leonardo yelled out, jumping.

“Mom!” Hovey said in English, waving and leaning over the railing.

They ran across the terminal, hugged each other, crying and giving each other kisses.

“This is surreal,” Hovey said. “I’m happy but still sad.”

The three held hands as they slowly walked to the parking structure, talking about the situation back home in Kharkiv. Usenko said only a few buildings were standing, including their apartment complex. She feared this made it an even bigger target.

Hovey stopped walking, placed her right hand over her chest and gasped for air, thinking about her dad. Her phone was quiet, but she was still linked to the sirens.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.