- Share via

SAN DIEGO — Last year, Maqsood Rahimi celebrated Ramadan, a time of reflection, piety and charity, in the city of Kabul, where he grew up.

He heard the adhan, the call to prayer, broadcast from a nearby mosque. He broke his daily Ramadan fast with dates in the two-story compound where he lived with his parents, younger brothers, wife and newborn daughter.

That was before the United States began withdrawing its remaining troops from Afghanistan. Before the Taliban began systematically taking over provinces and cities. Before Rahimi’s fear grew that his work with the Marines, which had nearly killed him once, would now kill him for sure.

Rahimi fears for the safety of his loved ones in Afghanistan; he is using a family name instead of his last name for their protection.

On Saturday night, Rahimi broke fast in a San Diego hotel at the start of Islam’s holiest month. He heard the adhan sound from a cellphone. He knelt on white bedsheets to pray.

It was the 31-year-old’s first Ramadan meal in the U.S. after he, his wife and their daughter fled Kabul in August. He spent the evening with half a dozen other refugees and the Marine who helped him escape.

“As long as we’re all together, we don’t feel like we’re separated from family,” Rahimi said as he held his 15-month-old daughter. “It feels good.”

Thousands of refugees who have left Afghanistan since summer are celebrating Ramadan in the U.S. Some are marking the holiday from their new apartments, others from hotel rooms, as resettlement organizations struggle to find them permanent housing in an expensive market.

In an attempt to bring the newcomers some semblance of home, the San Diego Afghan Refugees Aid Group hosted iftar, the sunset meal to break the fast, in the hotel. The grass-roots organization plans to hold the meal at other hotels in the area where refugees are staying and to find volunteers to take them to nearby mosques to pray.

“We want them to feel a sense of community, even though it’s their first Ramadan by themselves,” said Zulaikha Rahim, secretary of the group and a first-generation Afghan American. “We want to make them feel at home, even though their new normal looks very different.”

::

Rahimi was 19 when he began working as a linguist. It was his job to help Marines communicate with contractors and other Afghans. He described the troops as “a family, as a team.”

In 2011, Rahimi was in a “mine-resistant ambush-protected” vehicle when it ran over a 100-pound roadside bomb. The gunner, positioned at the top, was thrown from the vehicle. Although severely injured, he survived. Rahimi was left dizzy and scared, but unharmed.

“We were blessed,” Rahimi recalled.

Collin Hannigan, then a Marine captain, was one car behind and witnessed the blast. If not for the design of the vehicle, he said, the passengers “would have been killed.”

Rahimi worked as a linguist for almost four years before quitting and going back to school to study for his bachelor’s degree in business administration. He got a job at a telecommunications company. Over the last decade, he has kept in touch with Hannigan.

Hannigan, a San Diego resident, left the Marines in 2014 after seven years. The 39-year-old now works for a company that helps businesses hire military veterans.

Last year, as the situation in Afghanistan rapidly deteriorated, Rahimi and Hannigan communicated more frequently. One morning, Hannigan awoke to a message from Rahimi about the Taliban that read: “The bad guys are all now here.”

“He was in a country which was now completely controlled by the people that wanted to have him killed and that he fought against for three or four years,” Hannigan said. “In the blink of an eye that happened.”

Hannigan had helped three other interpreters get their visa packages through, although he faced more difficulties with Rahimi’s for an unknown reason. But he kept trying to get the former linguist out.

He finally managed to link up with the office of Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) through Joe Kristol, a Marine he’d served with. Hannigan was able to tell Rahimi’s story. He described the mission in which the interpreter had almost died. He talked about Rahimi’s service to U.S. troops and the danger he now faced.

Cotton’s staff, Hannigan said, set up Rahimi’s contact at the Kabul airport so he could leave the country. Within days of his family’s departure, twin bombs struck near the airport entrance. About 170 Afghans and 13 U.S. service members were killed.

::

It was Hannigan who picked up Rahimi’s family at the airport in San Diego when they arrived in January. Rahimi had chosen to resettle in the city because of his Marine friend.

Rahimi is one of 2,145 Afghan refugees who have arrived in San Diego County through February. The majority who resettled in the area have a relative or friend there.

In a letter to President Biden last month, San Diego County Supervisor Joel Anderson requested assistance from the administration to help the county resettle Afghan refugees and prepare to potentially receive more refugees, this time from Ukraine.

“The citizens of San Diego are once again willing to welcome the displaced with open arms,” Anderson wrote. “However, to do so successfully will require additional funding from the Administration to support this population.”

Sayed Omer Sadat thinks about what would have happened to his three daughters had the Taliban seized him because of his work for the U.S. military.

Etleva Bejko, director of refugee and immigration services for Jewish Family Service of San Diego, said the biggest challenge for resettlement agencies has been finding housing for refugees.

“There has been a shortage of rental units available,” Bejko said. “It’s not an Afghan evacuee issue; it’s not a refugee issue; it’s a California issue.”

The lack of housing presents additional challenges, Bejko said, including school enrollment and access to other services, such as English-as-a-second-language classes.

Farid Obaid, whose family is temporarily living in a Del Mar hotel, said his children were getting rides to school thanks to nearby church parishioners. There were no buses set up to take them. They don’t have the money to buy a car.

“Unless a family is settled into their permanent housing, they are still in that limbo period,” Bejko said. “In that period where they are still waiting for the next step to truly rebuild their lives here.”

::

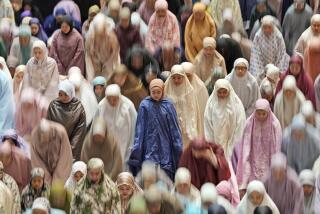

Nearly a dozen people gathered in the hotel’s breakfast room on Saturday evening to celebrate Ramadan.

There were placards left over from the morning that read “French Toast,” “Cheese Omelette” and “Seasoned Potatoes.” But the trays arrayed before the group now held qabili palau, a brown rice with chicken; challow, white rice; Afghan-style chicken korma; and bonjan, an eggplant side dish.

On smaller tables, Rahim and her sister-in-law, Wajma Rahim, had laid out water bottles; dates; bolani, a stuffed flatbread; and aush, an Afghan noodle soup, for everyone to grab as soon as the sun set, signaling the end of the day’s fast.

They have gotten to know the families through the Afghan Refugees Aid Group and have helped deliver groceries and other necessities. Zulaikha’s and Wajma’s parents fled Afghanistan 40 years ago.

“There was really no difference between them and myself, and any of us, but luck and timing,” Wajma said.

Among those gathered Saturday evening was Omid Sediqi, 26, whose father was killed by a suicide bomber last year. He and his family have bounced around hotels for a few months, waiting for permanent housing.

Sediqi arrived in San Diego with his mother and two brothers but left behind other siblings in Afghanistan. This year, he said, Ramadan felt different.

“It’s so difficult because of your family you left in Afghanistan to come here,” he said.

Soon after 7 p.m., as the sky darkened, everyone reached for sustenance after hours without food or drink. Rahimi snacked on dates and then filled a cup with dogh, a traditional Afghan yogurt, to give to his guest, Hannigan.

The Marine recalled trying the drink during his deployment when he and Rahimi were visiting a village elder.

Rahimi joined a few other men as they kicked off their shoes and knelt on bedsheets they had snagged from housekeeping, a far cry from traditional prayer rugs. They pressed their foreheads to the ground as Sam Smith’s “Like I Can” filtered down from the speakers overhead and then segued into electronic dance music.

Afterward, Rahimi guided Hannigan to a seat at his table, often referring to his friend as “bro.” With Rahimi’s brothers back in Afghanistan, he said of Hannigan, “he’s my brother.”

Since Rahimi’s arrival, Hannigan has taken the family to the beach and around San Diego.

As the group filled plates with traditional Afghan food that refugees had cooked in their hotel rooms, they conversed in Dari and English. They played with Rahimi’s 15-month-old, who had recently been released from a hospital with a feeding tube to help bring up her weight. The girl had started walking just two weeks before.

Although nearly 8,000 miles away from Afghanistan, that night they didn’t feel so far from home.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.