With a third year of drought, Southern California facing a hot, dry summer

- Share via

Memorial Day, the unofficial start of summer, is Monday. What’s in store for the upcoming season of beach days and barbecues in Southern California?

To start with, it will be dry. That’s not just because California’s Mediterranean climate means rain mostly falls during a few wet winter months, but because the state is in its third year of drought.

This year, after an unusually wet December, California experienced the driest January, February and March on record — some of the very months when the state expects to get almost all of its precipitation. California’s precipitation typically comes in a handful of winter storms. The state averages seven strong atmospheric rivers during the October-to-September water year, according to the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego. The state kicked off the 2021-22 water year with an exceptional atmospheric river on Oct. 28, but then ended up with only five strong ones for the whole winter, making it the third straight water year with below-normal atmospheric river activity.

Warm days prematurely melted the snow that was stockpiled high in the mountains early in the season. The snowpack in the Sierra usually serves as cold storage for a big portion of the state’s water supply. It gradually melts during the spring and summer, feeding rivers and reservoirs, and supplying cities and farms. By April 1, the snowpack had dwindled to just 38% of average. Major reservoirs statewide were at 76% of average levels this week, with the long, hot summer months still ahead.

After three bone-dry months, precipitation during April gave Northern California a brief reprieve, but those springtime amounts fell far short of what is necessary to alleviate the prolonged drought.

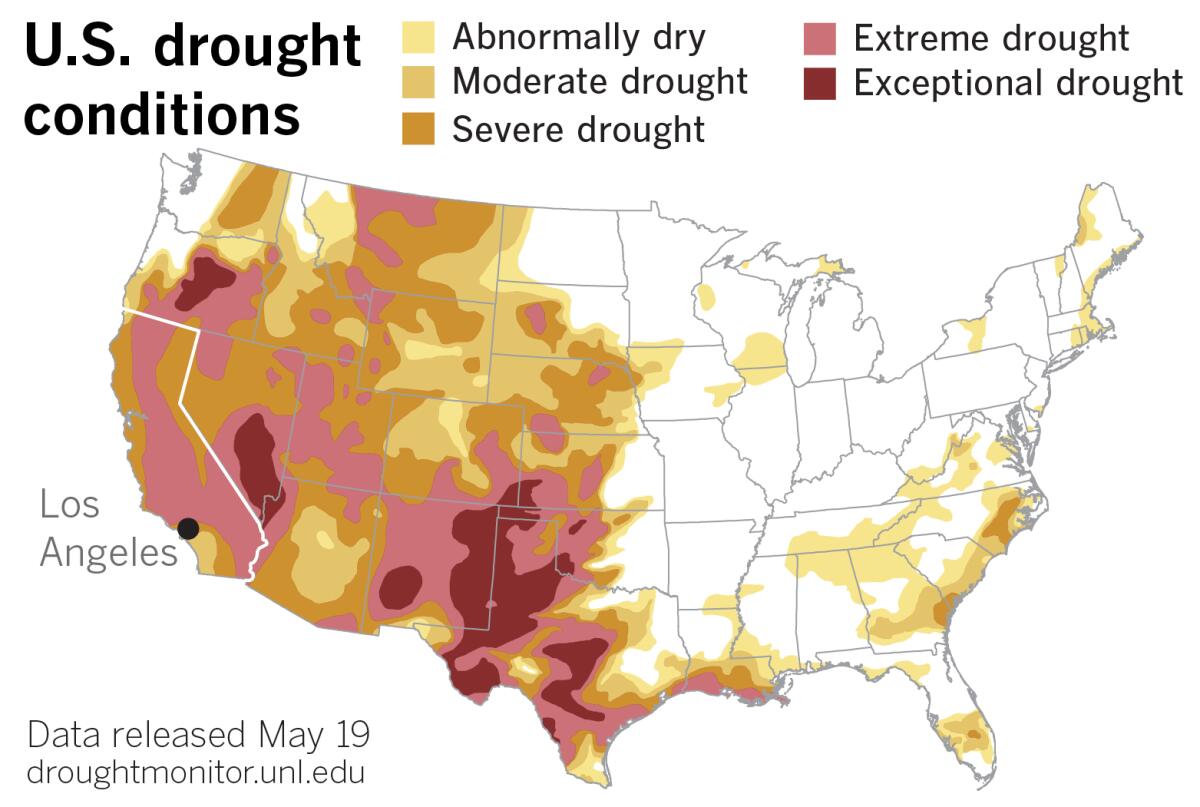

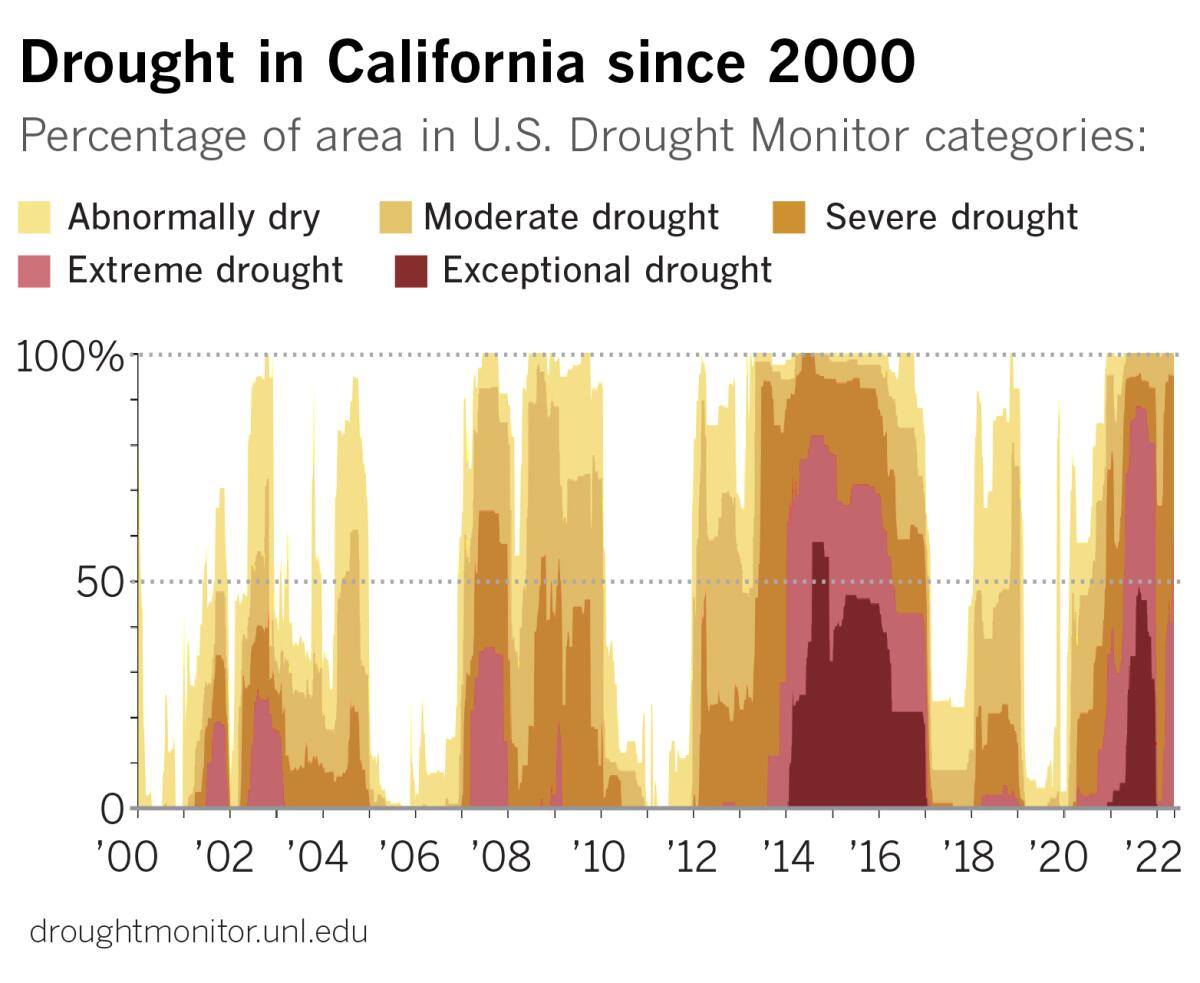

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, extreme drought continues to expand. A timeline of the percentage of California subject to drought since 2000 illustrates the long view that the state has been locked in drought, with a few intermittent wet years, for more than two decades. Scientists say this has been the driest 22-year period in at least 1,200 years.

During that 22 years, the longest period when the state was besieged by moderate to exceptional drought lasted 376 weeks, from Dec. 27, 2011 to March 5, 2019. The most intense week was in late July 2014, when 58.41% of California land was categorized as being in exceptional drought, the worst category.

This month, 59.64% of the state is categorized as being in extreme drought, the second-worst category, with just 0.18% in exceptional drought — but then this is May, not July.

Drought has a cumulative effect. As the drought has intensified, exacerbated by climate change, Gov. Gavin Newsom recently warned that mandatory statewide water restrictions may once again be necessary, as they were when Jerry Brown was governor.

Evidence of a warming planet is apparent in global temperature readings. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said this month that April 2022 tied with April 2010 as the fifth-warmest April in the 143-year record. The 10 warmest Aprils have occurred since 2010, and the months of April in the years 2014-2022 have all ranked among the 10 warmest on record.

Above-normal temperatures increase evaporative demand, which is essentially a measure of how thirsty the atmosphere is. It’s a way to quantify the loss of moisture due to such factors as temperature, wind speed, humidity and solar radiation. Periods of above-normal temperature and elevated evaporative demand dry out soils and vegetation, making plants more stressed and flammable, which favors rapid spread of wildfires.

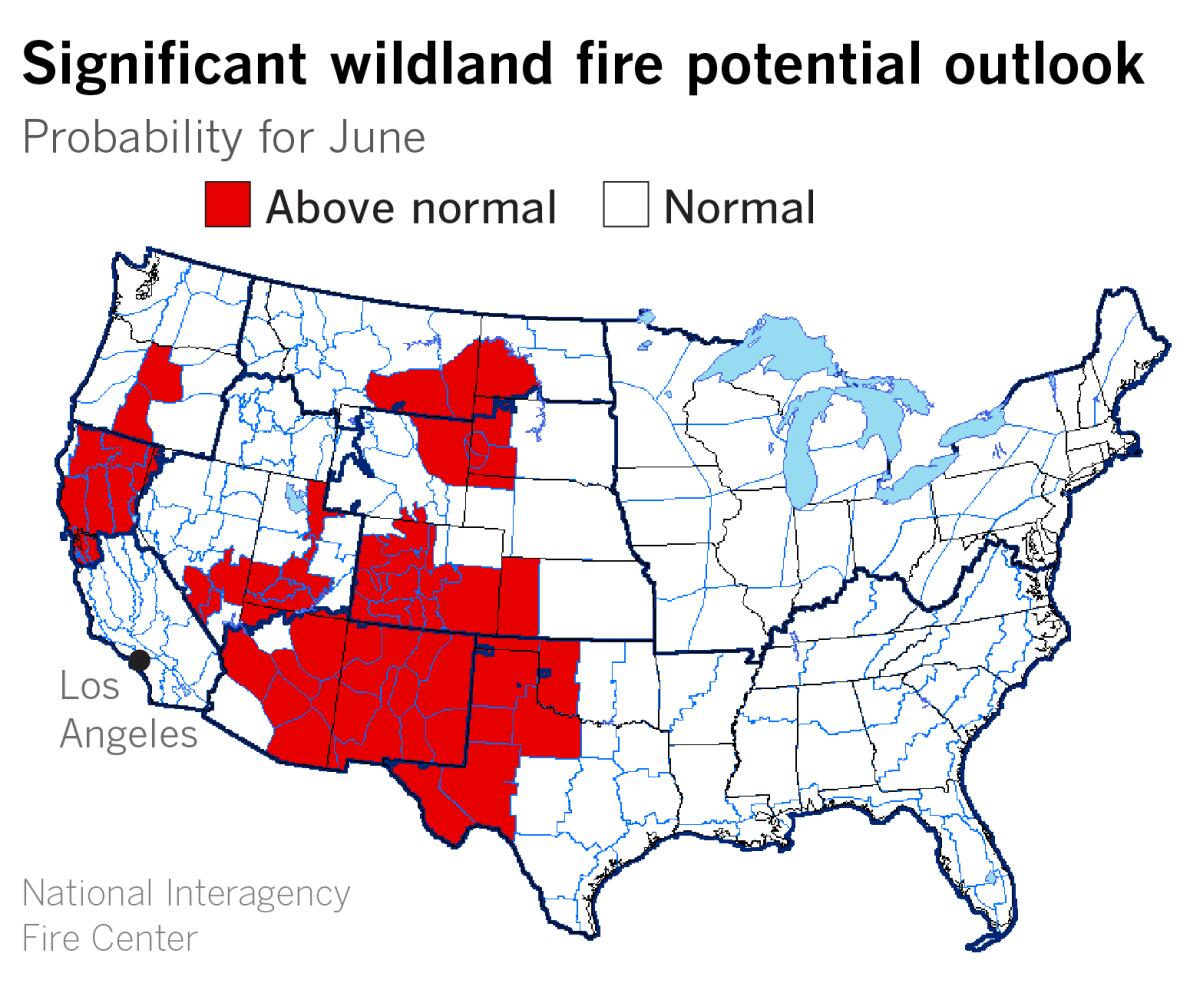

The National Interagency Fire Center forecasts above-normal potential in June for significant wildland fires in Northern California, mainly north of the Interstate 80 corridor, with the rest of the state expected to see normal fire potential.

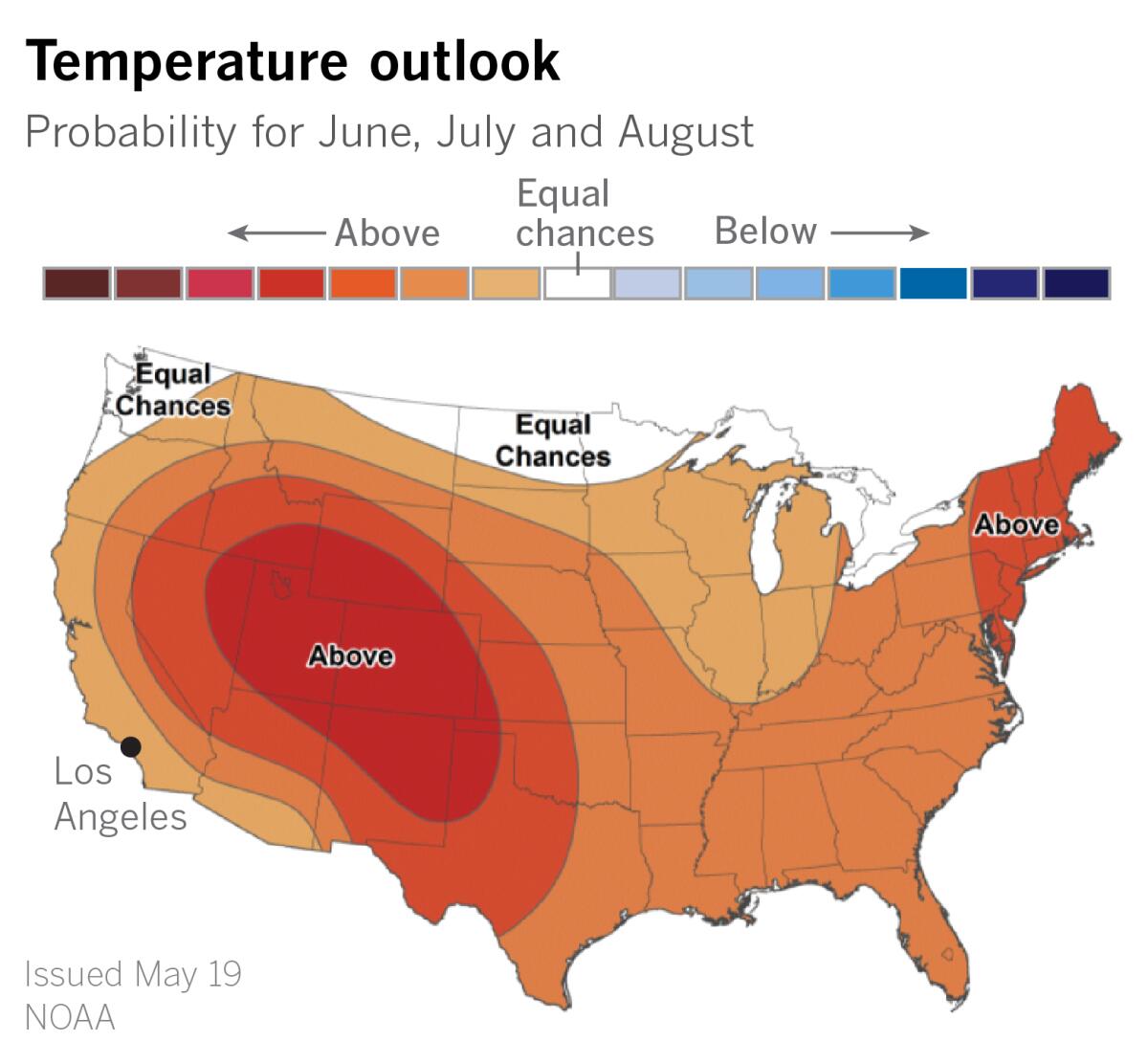

An outlook for June, July and August issued by the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center this month calls for above-normal mean temperatures for most of the U.S., with the highest probability over a large portion of the West. Coastal California has a 33% to 40% probability of above-normal temperatures. Inland deserts, valleys and mountains have a 40% to 50% chance of above-normal temperatures.

The highest likelihood for above-normal temperatures is in the central Great Basin and the central and southern Rockies, part of the area drained by the Colorado River. The Los Angeles region typically depends on the Colorado River for about a quarter of its water, according to the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

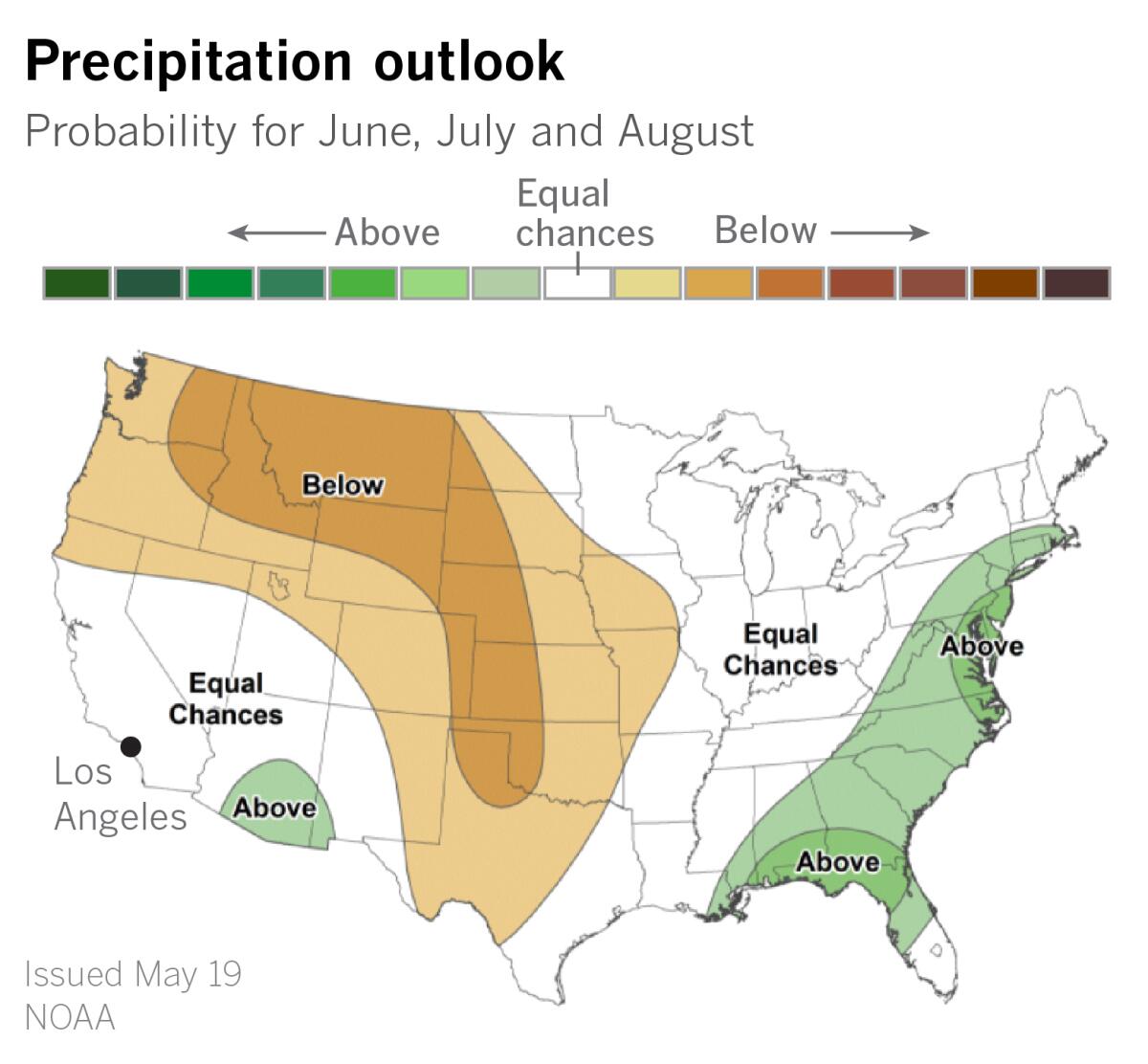

The precipitation outlook for the June-to-August period calls for below-normal rainfall from the Pacific Northwest into the Plains, including the Rockies and the upper Colorado River watershed. Most of California falls in an area with equal chances of above, near-normal or below-normal rainfall. But normal rainfall during the summer months in California is essentially none, given the Mediterranean climate.

A bright spot in the outlook for the Desert Southwest includes above-normal prospects for an enhanced monsoon. In northern Arizona, 40% to 50% of annual rainfall occurs during the monsoon. Southern Arizona gets about 32% of normal yearly rainfall during the monsoon.

“The monsoon season can bring higher humidity to Southern California, which can lead to more uncomfortable nights on the tail end of a significant heat wave,” said Eric Boldt, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Oxnard. The season usually begins just after July 4 in L.A. County and continues into September, he said.

The monsoon season can bring thunderstorms to the mountains around L.A., and that can mean lightning strikes. But there has been very little monsoon thunderstorm activity in the mountains over the last two or three summers, he said. Last season the thunderstorm activity remained mostly over Arizona and eastward. “You could say we’re overdue, but that does not influence the outlook since we remain in a La Niña pattern like a year ago,” he said.

Back-to-back La Niñas might be responsible for the active Southwest monsoon forecast, but we were in a La Niña in 2020, and that was a poor monsoon year, said Alex Tardy, a meteorologist with the weather service in San Diego. In that year, a stronger-than-usual upper-level ridge was directly overhead, generating excessive heat. While we had no monsoon in 2020, the monsoon was active in July, August and September 2021. There were 10 separate coastal thunderstorms from L.A. to San Diego, even into early October, making 2021 the most active for such events since the summer of 2015, Tardy said.

Equatorial sea surface temperatures and atmospheric conditions in the tropical Pacific are consistent with La Niña, according to NOAA. During the last four weeks, below-average sea surface temperatures strengthened in the Niño 3.4 region, which straddles the equator in the eastern Pacific. Enhanced convection was observed over the Philippines, also consistent with La Niña. Convection is the process by which heated air and moisture rises and produces clouds and thunderstorms. Stronger east-to-west trade winds push warm water into the western Pacific, where it causes more evaporation, more clouds and more rain, as well as more tropical cyclones or typhoons.

La Niñas are associated with dry winters in the U.S. Southwest. They’re also connected to busy hurricane seasons in the Atlantic Basin. This week, NOAA predicted that 2022 will be the seventh consecutive above-average Atlantic hurricane season. NOAA said there was a 65% chance that the season, which runs from June 1 to Nov. 30, will be above normal. The outlook called for 14 to 21 named storms, of which six to 10 could become hurricanes. That number could include three to six major hurricanes, meaning categories 3, 4 or 5.

Meanwhile, in the central Pacific, there is a 60% chance of below-normal tropical cyclone activity, NOAA said. “The ongoing La Niña is likely to cause strong vertical wind shear making it more difficult for hurricanes to develop or move into the central Pacific Ocean,” said forecaster Matthew Rosencrans.

La Niña is expected to continue, with the odds decreasing in the late summer before increasing through fall and early winter.

With all the factors, including climate change, worsening drought, dwindling reservoirs and potentially mandatory statewide water restrictions, summer heat and fire danger, a paraphrase of Margo Channing’s advice in “All About Eve” might be appropriate: “Fasten your seatbelts; it’s going to be a bumpy summer.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.