- Share via

SAN DIEGO — The request, passed down through the generations, came from a grieving father whose son was missing and presumed dead after the attack at Pearl Harbor.

“If they ever find the body,” he said, “please make sure somebody steps up and takes care of things.”

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

Eighty years later, the promise is being kept. Paul Gebser is coming home.

He’s coming home to San Diego and a burial Friday at Ft. Rosecrans National Cemetery. There will be full military honors for the 38-year-old Navy sailor, who was stationed on the battleship Oklahoma during the Dec. 7, 1941, aerial assault by Japan that shoved the United States into World War II.

Gebser’s journey to a final resting place is the result of a painstaking Department of Defense project, concluded late last year, that used forensic anthropology, medical and dental records, and DNA testing to comb through some 13,000 bones commingled in mass graves and match the remains with names.

Of nearly 400 sailors and Marines from the Oklahoma who were buried as “unknowns” after the war, all but 33 have been identified.

“It just means closure for us, a chance to say goodbye,” said Paul Beahan, a Los Angeles filmmaker who is Gebser’s great-nephew and is named after him. “It’s what the family always wanted.”

Beahan never met Uncle Paul, who died before he was born. But he grew up hearing stories from his grandmother, Gebser’s sister, about their life in Ocean Beach. Before she died in 2005 at age 95, she passed along a journal he kept, letters and photos.

And she told him about his great-grandfather, Henry William Gebser, the one who extracted that promise all those years ago to do the right thing if the body was ever recovered.

“My great-grandfather had already lost two daughters to tuberculosis, and then three or four years later his only son at Pearl Harbor,” Beahan said. “It killed him, not knowing for sure what had happened.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

A headstone, but no body

Paul Heino Gebser was born in Kansas City, Mo., on July 25, 1903, to an aristocratic family with deep roots in the Germanic kingdom of Prussia. One ancestor was a German chancellor. A cousin was Jean Gebser, the philosopher and poet best known for his work on consciousness.

The Gebsers settled in Ocean Beach when Paul was young and he went to local schools. He joined the Navy through a sense of patriotic duty fueled by his family’s loss of property and titles amid government upheaval in the late 1890s and early 1900s in Germany, Beahan said.

“They saw what happened when a country doesn’t protect itself,” he said. “Paul wanted to protect this one.”

He lied about his age to enlist at 17, Beahan said. After 14 years in, he left the service and returned to San Diego to build boats for six years before re-enlisting in 1940.

That same year, the ship he was assigned to, the Oklahoma, was sent to Hawaii and based at Pearl Harbor. It was a storied ship, used to protect convoys crossing the Atlantic during World War I and to evacuate Americans from Europe during the Spanish Civil War.

On Nov. 20, 1941, Thanksgiving Day, the Oklahoma was moored on Battleship Row at Pearl Harbor, west of Honolulu. Gebser wrote his parents a letter that day. The machinist’s mate, first class, was bored and a little sluggish. He’d just had a big meal — so big that “I don’t feel much like going anywhere,” he wrote. “Good chow.”

He said it wasn’t clear when he might be able to come home for a visit. He doubted it would be before May. “Well, that’s not so terribly long off, only 5 months,” he wrote.

Gebser’s parents received the letter in early December, within a day or two of the Japanese attack, Beahan said.

The Oklahoma was hit that morning by eight torpedoes. In less than 12 minutes, she had rolled over. Hundreds of sailors and Marines were trapped in the wreckage.

In Ocean Beach, his parents awaited word of his fate. There were no cellphones in 1941, no internet. They knew from media accounts that many of the Oklahoma servicemen leaped from the ship before it capsized and swam to safety. Navy civilian workers had rescued 32 others by cutting through the hull with blowtorches and chipping tools.

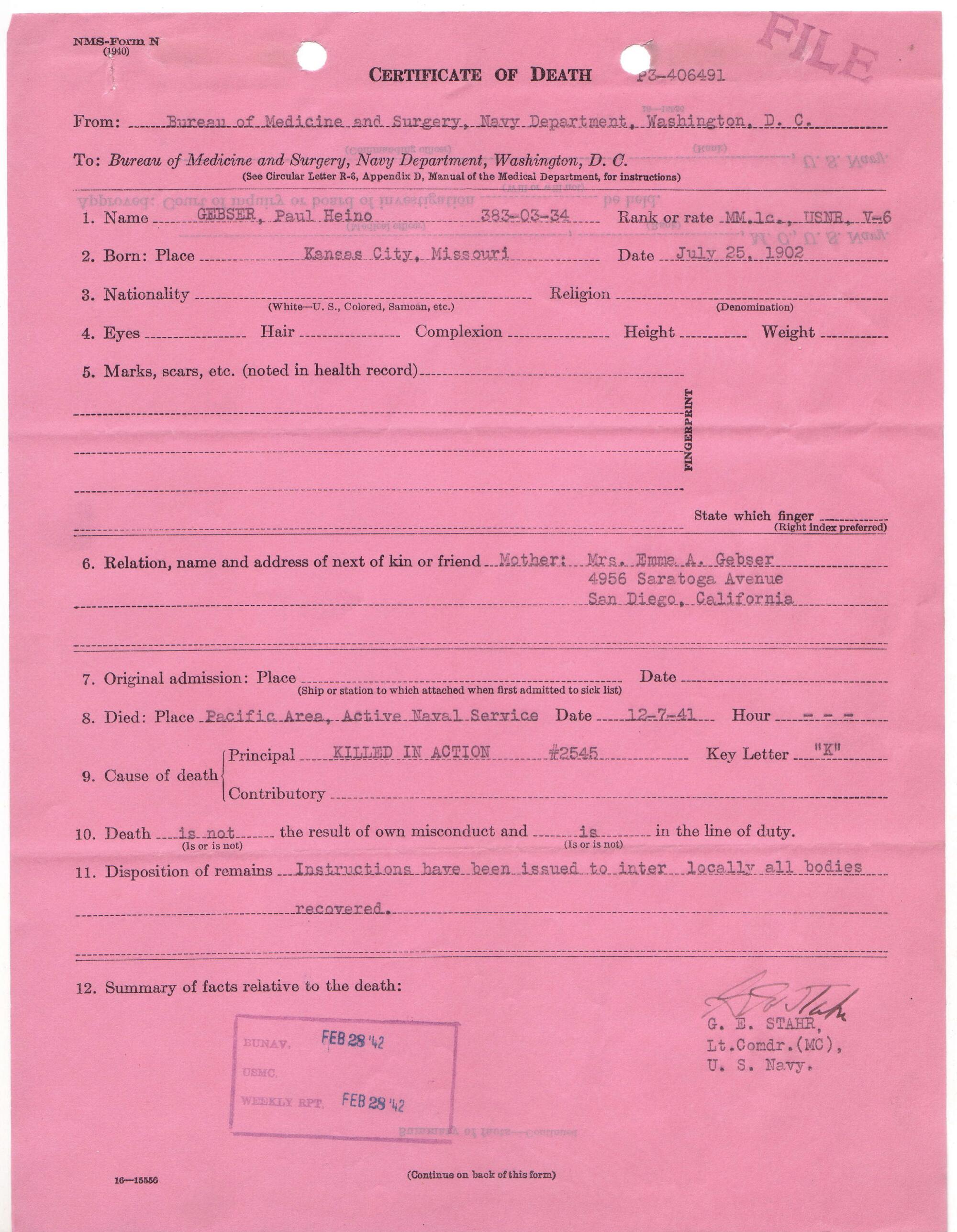

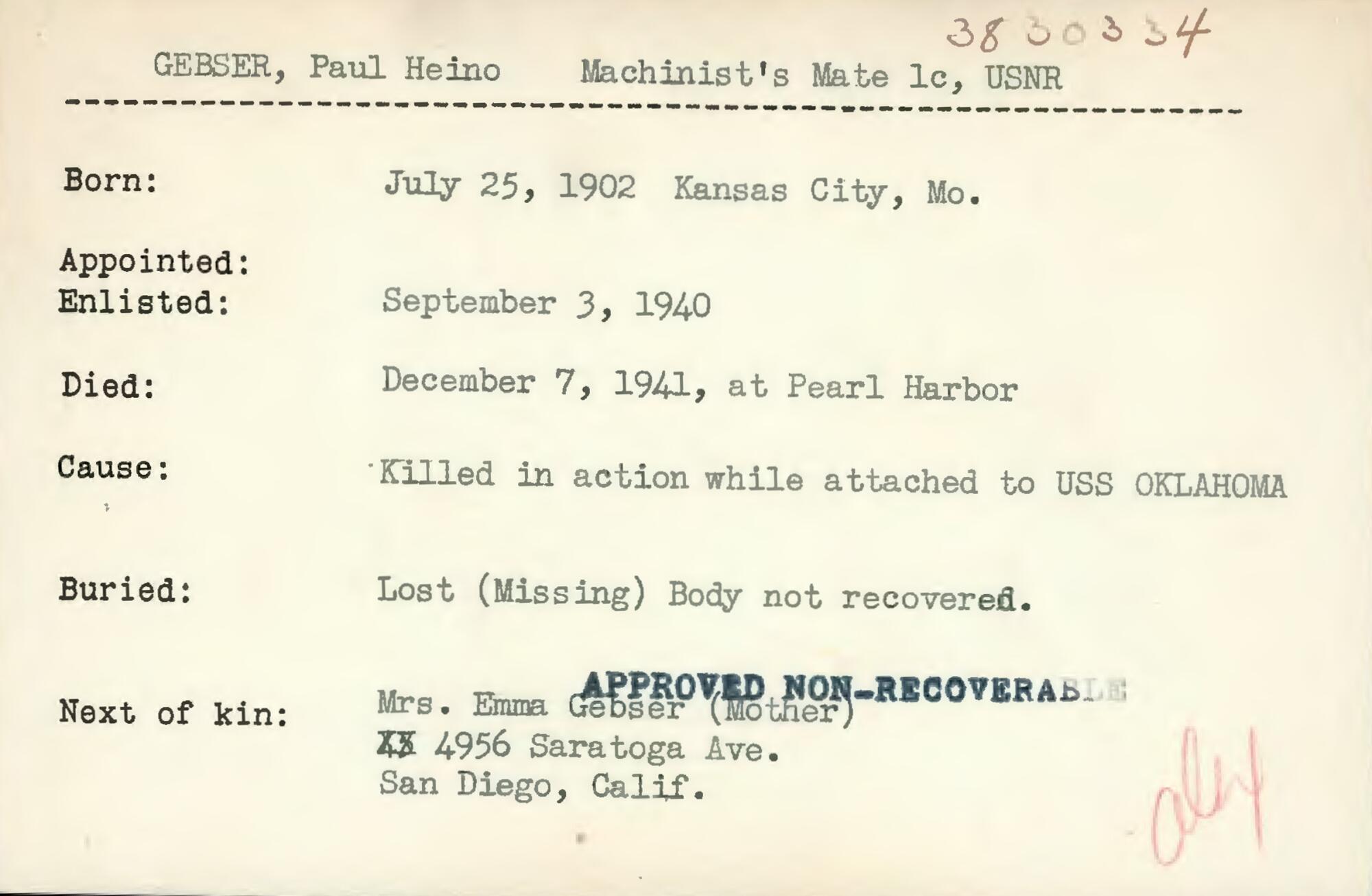

Then, in February 1942, two months after the attack, a notice arrived at the Gebser house on Saratoga Avenue. It was from the Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. Across the top, in capital letters and black ink, three words erased all hopes the family may have harbored about their son’s survival.

“CERTIFICATE OF DEATH,” it said.

The form reported that he had been killed in action on 12-7-41. Under the section for “Disposition of remains,” it said, “Instructions have been issued to inter locally all bodies recovered” — locally meaning Hawaii.

The family decided to buy a plot at Mount Hope Cemetery in San Diego and erect a headstone with Gebser’s name on it, in hopes that one day they’d have a body to bury beneath it.

The headstone includes a photo of Gebser in his Navy uniform. Along the bottom it says, DIED IN DEFENSE OF HIS COUNTRY.

And in the right-hand corner there’s this, a declaration that’s both a promise and a plea: REMEMBER PEARL HARBOR.

Sixty-one caskets

After the attack, crews began salvaging the Oklahoma. Bodies were recovered by divers — a few here, a few there — and sent to two nearby cemeteries. Eighteen months later, with the ship again upright, about 400 of the slain had been pulled from the wreckage and buried, some with names attached, the others as “unknowns.”

Three years later, as part of a wider War Department effort to identify the fallen from World War II, the remains were disinterred and taken to a laboratory. Identifications were confirmed for 35 of the bodies.

The rest were classified as “non-recoverable” and commingled, segregated into similar skeletal pieces to reduce the number of caskets required. They were buried in 46 plots at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, a Honolulu graveyard commonly known as Punchbowl for the volcanic crater it occupies.

In the early 2000s, after prodding by a Pearl Harbor survivor with an interest in anthropology, military officials removed one of the caskets to attempt a new round of identifications.

They thought they would be combing through the remains of a handful of Oklahoma crew members. Instead, the casket had bones from about 100 people, a foreshadowing of the complexities ahead.

That project led to five of the sets of remains being identified and sparked additional calls from veterans groups and the shipmates’ families to pursue more investigations. To help in the effort, relatives of the slain were asked to provide DNA samples.

In 2015, the remains — 388 bodies still unidentified — were disinterred again and sent to Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency labs in Hawaii and Nebraska.

What they received were 61 caskets. Inside each were bundles of bones wrapped in white cloth and fastened with large safety pins. Most of the caskets had five or six bundles, but one had almost two dozen.

The contents of the bundles varied. In one casket, nothing but upper arm bones from multiple people. In another, neck vertebrae.

“Even when the bones were put together in a bundle as one person, we had to look at it closely because most likely it wasn’t from just one,” said Carrie LeGarde, the lead forensic anthropologist.

They inventoried 13,000 bones and extracted DNA where they could, comparing it to 5,000 samples collected from the relatives of the Oklahoma shipmates.

It was challenging work, but rewarding, too, LeGarde said. Lab workers put photos of the men they were trying to identify on the walls of their cubicles, reminders of what was at stake. One family had lost three sons on the ship. Another had lost twins.

When a match happened, “There was excitement and a sense of relief that we reached this point and we know it’s him,” LeGarde said. “And the family, at long last, is going to find out.”

A match is made

The hunt for Gebser had some advantages.

One was his age, 38, older than the majority of his shipmates. Bones degrade over time, changes that are noticeable at the joint surfaces. That made locating his skeletal pieces easier.

He also used dentures, an upper plate that the anthropologists knew about from his dental chart. A skull that’s missing a dental plate looks different than one that still has teeth or has lost them due to trauma.

Beahan said he and other relatives were asked several years ago to provide DNA samples via cheek swabs. The request came in an email from a genealogist working with the forensic lab. He thought it was a prank at first.

“They said they believed they had his remains and that they had the technology to identify him,” he said. “Just the fact that they could do that — it surprised me.”

In September 2019, a positive match was made. Investigators had used dental records, anthropological analysis and DNA extracted from Gebser’s left tibia.

A notebook sent to the family that details the findings includes a photo of an almost entirely intact skeleton, Beahan said.

At first, they planned to have the body buried at Mount Hope under the headstone that is already there. But cemetery officials told them there isn’t room for the casket. Turns out that after Gebser’s father died, his ashes were put in an urn and buried in the plot. The ashes of another relative are there, too.

So the funeral will be at Ft. Rosecrans, the 82-acre national cemetery at the tip of Point Loma, not far from where Gebser grew up. (One of his sisters, Loma, was named for that spit of land.)

Some 77,000 service members from the nation’s military conflicts, dating to the Mexican-American War in the 1840s, are interred there, including a couple others from the Oklahoma previously buried in Hawaii as “unknowns.”

About 20 people are expected to attend Friday’s service, including some who have never met. That means the memorial will be a family reunion, too.

Beahan said that’s only fitting.

“Paul was the glue that held everyone together, and after he was lost, the family fragmented,” he said.

Found now, he’s again bringing people together, a wish fulfilled 80 years later.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.