With Roe dead, antiabortion religious groups insist they want to help mothers

- Share via

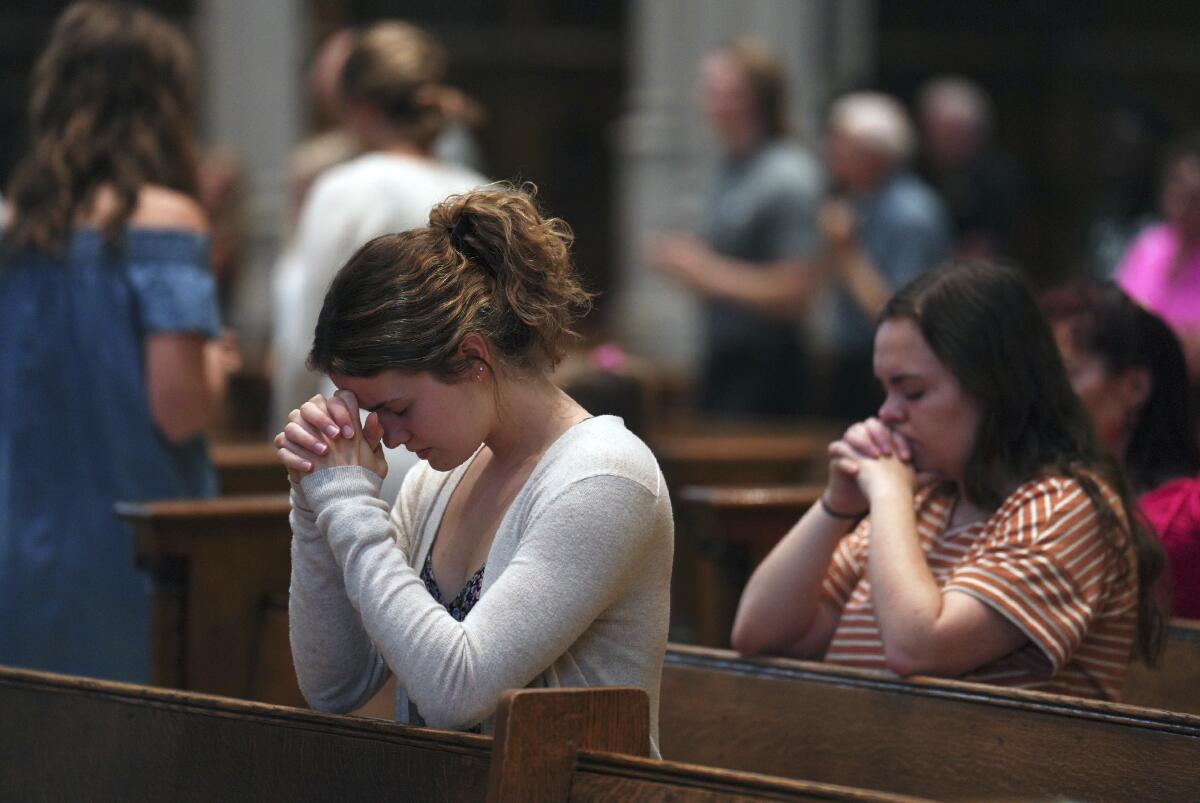

For Southern Baptists across the nation, Friday was a day of triumph, rejoicing and praising God.

After 50 years of legal battles and prayer, Roe vs. Wade was overturned as the Supreme Court declared a woman’s right to an abortion is not protected by the Constitution.

But even as millions of Southern Baptists celebrated what they regard as a historic victory, their president, Bart Barber, was already telling the denomination’s 47,000 member churches that it was time to roll up their sleeves and get to work, especially those in states like Texas, where a trigger law made abortions illegal the moment the court decision was announced.

There are more than 2,500 pregnancy centers across the country, including 200 in Texas. With Roe vs. Wade expected to fall, those numbers are poised to grow.

The world was watching, Barber suggested, and evangelical and Catholic organizations that have waged war against legalized abortion would need to show that mothers, as well as their unborn children, would be supported and thrive in a post-Roe America.

“There are people across the country that are having some fear today,” Barber said in a live video streamed by the Baptist Press. “But if our congregations can help people have healthy outcomes that lead to healthy families ... then we can show California and other states that the world is not coming to an end in Texas. Women are not deprived of the opportunity to flourish in Texas. It’s not ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ in Texas.”

Catholic leaders struck a similar chord in the days since the court’s ruling: Overturning Roe vs. Wade did not represent the end of their work, they said. In some ways, it was just the beginning.

Antiabortion religious leaders for decades have insisted they care as much about the welfare of expectant mothers as they do about their unborn children. Now they will be under pressure from abortion rights organizations and their political allies, as well as women denied abortions and their families, to step up to help secure more funding and resources for expanded prenatal and child care, increased family paid leave, and help with smoothing adoption red tape and holding deadbeat dads and abusive partners accountable.

Whether they will is yet to be determined.

Less than 24 hours after the court’s decision, the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, the public policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, was reimagining its focus, said acting commission President Brent Leatherwood. He said the group would prioritize supporting legislation that he believes will help women facing unexpected and unwanted pregnancies such as bolstering the capacity for faith-based and community child-care providers and making insurance more family friendly.

“This is going to go myriad ways, and we are eager to be part of those,” he said. “Let’s make sure that families are moving to a place where abortion is not even thinkable.”

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, led by Archbishop José H. Gomez of Los Angeles, released a statement declaring that now was the time “to build a society and economy that supports marriages and families, and where every woman has the support and resources she needs to bring her child into the world with love.” Last year, the conference considered denying Communion to President Biden, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco) and other Catholic politicians who support abortion rights.

Bishop Oscar Cantú, of the Diocese of San Jose, issued a statement calling on state lawmakers to expand programs for housing assistance, prenatal and postpartum care, protection from domestic violence, paid family leave and maternity accommodations from employers as a way to better support pregnant women.

Erika Bachiochi, a legal scholar and fellow at the Ethics & Public Policy Center, wrote that true reproductive justice would not just protect and promote the health and well-being of unborn children and their mothers, but also “ensure that all women, especially the poor, have the financial resources, medical support and workplace accommodations they need to care for their children once they are born.”

For some critics of the antiabortion movement, impassioned calls for a social safety net from the victors of a bitterly fought war appear disingenuous and hypocritical. After all, they argue, shouldn’t policies that would ease the logistical and financial burden of birthing and raising children have been championed by people of faith even before America entered this new post-Roe reality? Many Republican and conservative supporters of abortion restrictions repeatedly have voted against programs that aid poor mothers and women and children of color in particular, these critics contend.

“You’ve had decades to show support for women through social programs and expansion of Medicaid, and those social supports have not been happening,” said Emily Reimer-Barry, a Catholic feminist theologian at the University of San Diego. “I find it disheartening that now pro-life folks feel they have an obligation to do something.”

Reimer-Barry, who does not speak for her university, said that she’s seen little concern for women’s issues within the Catholic world.

“I’m aware of a few initiatives here and there to drum up support for women, but we do not have great family leave policies in Catholic institutions, we don’t have women’s representation at every level of the church, and I can’t even get my own parish hall to have a baby changing station in the women’s bathroom,” she said. “We’re talking about basic inability to respond to women’s needs in parish settings.”

John Gehring, Catholic program director for Faith in Public Life, an advocacy organization based in Washington, said it’s difficult to generalize about Catholic institutions: Some do a better job than others at supporting women and especially pregnant women. Still, he said, there is often a gap between antiabortion advocates’ rhetoric and practice.

“It’s less important what church leaders say right now than what they do,” he said. “There are plenty of Catholic institutions walking the walk, but there are many dioceses and Catholic schools that are still not living up to our own teachings when it comes to providing robust, pro-family policies that support women.”

Kathleen Domingo, executive director of the California Catholic Conference, which lobbies at the state level for the 12 bishops of California, said it’s a myth that Catholics who support abortion restrictions care more about babies before they’re born than after.

“The Catholic Church is the largest provider of social services in the world,” she said. “We help foster youth, pregnant youth, the unhoused, and victims of internet and partner violence.”

Domingo said the bishops have tasked her with advocating for legislation that supports what is sometimes called “the seamless garment” or “a consistent life ethic,” the idea that all human lives are sacred and that Catholics have a responsibility personally and socially to protect and preserve the sanctity of life from “womb to tomb.”

This lens has led her to advocate not only for greater abortion restrictions in California, but also on behalf of immigration reform, increased access to affordable housing, common-sense gun legislation, environmental protections and paid family leave.

“We don’t just oppose abortion legislation,” she said. “It’s equally important to advocate for the social safety net.”

The Rev. Sam Sawyer, a Jesuit priest in New York City and senior editor of the Catholic publication America magazine, understands why critics are angered when bishops and other Catholic leaders make such statements as, “Now it’s time to get to work.”

“The church’s long-standing position, which the bishops have long articulated, is in support of a much more robust safety net than we have in the United States,” he said. “But when push came to shove, are you going to vote for someone with safety net policies or someone who will help you overturn Roe?”

Now that the battle over abortion rights has shifted from the Supreme Court back to lawmakers and lower courts, the church leadership might choose to mobilize politically behind a more robust social welfare and social safety net, including economic support for women and families — values that he says the church has supported forever.

“Now there is more opportunity for that support to be practically realized at the level of politics,” he said.

For Joy Qualls, associate dean at Biola University, a private evangelical university in La Mirada, the end of Roe doesn’t mean the beginning of the work of supporting families; it means the work continues and has to be broadened.

“Churches and religious nonprofits have been providing care to women and families for a long time and it has to expand now,” she said. “The time, energy, emotion and money has to be shifted in ways that don’t fit neatly into our political boxes.”

Qualls said she thinks social policies are more likely than laws to have an effect on whether women seek abortions.

“We know what impacts abortion — access to education, good paying jobs, contraception, access to economic security,” she said. “That’s where our attention and resources have to go. We have to pony up to the complexity of this issue.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.