California kindergarten saw big enrollment drop during pandemic. What’s happening now?

- Share via

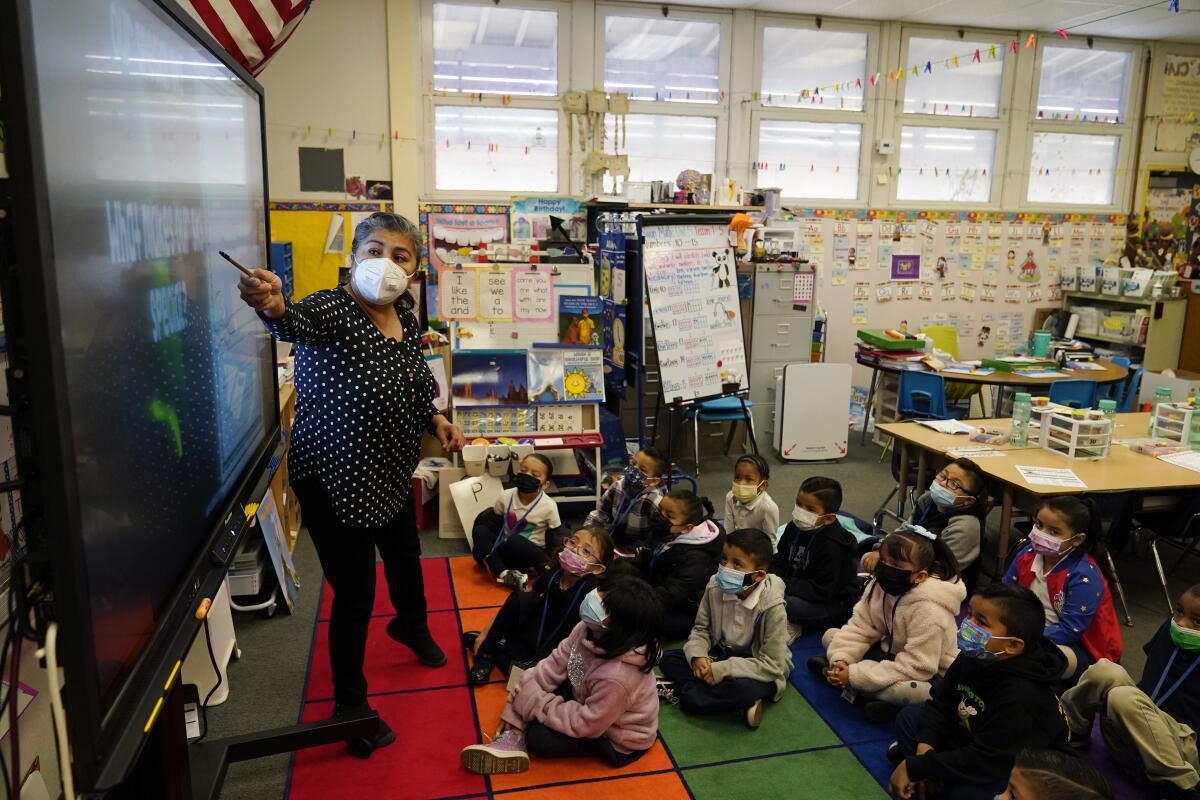

No grade level suffered a steeper enrollment drop during the COVID-19 pandemic than kindergarten, driven by what many parents saw as the futility of placing a 5-year-old in front of a computer all day.

When campuses reopened, enrollment somewhat rebounded, but an overall downward trend deeply worried educators, knowing the harm that missing kindergarten can mean for a child’s development.

For that reason, many expressed disappointment that Gov. Gavin Newsom on Sunday took a step back from a historic expansion of early education by vetoing one bill that would have made kindergarten mandatory and a second bill that would have required school systems to offer a full-day kindergarten.

These measures had widespread support from educators. Some considered them crucial to uplifting the academic, social and emotional well-being of families and students emerging from the pandemic. And the students most in need, they said, include Black and Latino children and those from low-income families.

“The majority of children who are not enrolled in kindergarten are from low-income Latino families,” said Pedro Noguera, dean of USC’s Rossier School of Education. “The research is very clear that kids who enroll in kindergarten are better prepared academically and socially for school in first grade, and more likely to be reading with proficiency by third grade.”

Newsom cited budgetary concerns while sidestepping the merits of the bills, calling attention to measures for expanded early education, extended-day academic enrichment and increased K-12 funding that he has taken.

Some advocates credited Newsom for supporting measures on which they place a higher priority. These include a massive expansion of transitional kindergarten that, in essence, offers a free — optional — public education in California to 4-year-olds for the first time.

Gov. Newsom’s budget is flush with money he has to spend on education. He sets sights on transitional kindergarten for all.

Groups representing the state’s school boards and school administrators expressed some relief that an additional mandate would not be added.

“The Legislature and the governor have been very ambitious and they’ve done a number of good things that are moving the needle ... and there is limited capacity to take more on,” said Edgar Zazueta, executive director of the Assn. of California School Administrators. For schools, the focus needs to be on “how can we successfully implement what we already have on the docket right now.”

Senate Bill 70 would have expanded compulsory education to include kindergarten, beginning two years from now. Assembly Bill 1973 would have expanded learning time for young students by requiring all elementary schools to offer at least one full-day kindergarten class by 2030-31.

The plunge in kindergarten enrollment helped fuel the push to make that grade mandatory.

Enrollment in kindergarten dropped far more than in any other grade during 2020-21, when most public schools spent much of the year in remote learning with campuses closed.

In 2019-20, kindergarten enrollment statewide was 523,009 and it dropped 11.6% in 2020-21 to 462,172. The decrease was even greater — 14% — in Los Angeles Unified, the state’s largest school system.

“Remote learning is very difficult at the kindergarten level,” said Troy Flint, a spokesman for the California School Boards Assn. “You have kids that oftentimes have never been in a structured environment before — and you’re asking them to learn over computer. Many parents just opted out of that.”

Parents had the choice of opting out because kindergarten is not mandatory. Some parents switched to private school; others chose an extended preschool experience or settled for day care or informal baby-sitting. For families who could not afford such alternatives, older siblings provided a great deal of child care as well.

The alarming dip in math proficiency and smaller declines in English in the last two pandemic-disrupted school years hit students who were already behind.

Kindergartners from that year are now in the second grade — and they should be benefiting from various programs to catch up, such as tutoring.

With in-person schooling back in the fall of 2021, kindergarten numbers across California rebounded more than in any other grade, rising 1.7%. In L.A. Unified, however, enrollment fell further, by an additional 6%, officials said. The district was among the strongest backers of the mandatory kindergarten bill.

Statewide, all grades — except kindergarten and grade 12 — continued to decline last year, in line with the state’s overall declining enrollment.

The state has not yet released enrollment figures for this year.

One concern raised by Newsom’s vetoes will be the “equity question,” said Anna Markowitz, assistant professor at the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies.

“As California moves to offering universal access to pre-kindergarten, you could be living in a world where at the start of the first grade year some kiddos have fully two years of school experience under their belt and some have none,” she said. “That’s going to be a challenge for teachers and for kids.”

She’s hopeful that the expanded access to public school for 4-year-olds would increase participation in kindergarten.

Newsom missed an important opportunity to help the youngest victims of the pandemic, said early literacy advocate Maya Payne Smart.

“Wasting this chance to give more kids the screenings, lessons, words and book experiences of kindergarten is particularly ill-timed,” said Smart, a faculty member in the College of Education at Marquette University. “It means many children with greater-than-usual need for language and literacy interventions will receive it a year later, if at all. This is a tragedy because history shows that reading foundations delayed all too often lead to reading proficiency denied.”

Even if signed, the bill to provide full-day kindergarten would not have solved the issue of child care for families, who have difficulty accommodating full-time work schedules, said Michael Olenick, head of Child Care Resource Center in the San Fernando Valley.

“A full school day is about six hours — where a family often needs eight to 10 hours of care,” Olenick said. “I think that trying to make K work for those families who need a full-day, full-year option in order to work is what is precluding them from enrolling them in K.”

The mandatory kindergarten bill was authored by state Sen. Susan Rubio, a former teacher whose L.A. County district includes Baldwin Park.

“Any teacher who has been in the classroom as long as I have can describe to you in detail the long-term, devastating effects to a child who misses kindergarten,” Rubio said in a statement. “I plan to reintroduce my mandatory kindergarten bill and fight for the funding next year. Our children are too important. We can either pay the education costs now or the far greater societal costs later.”

Research supports her position.

A study of 11,571 students in Tennessee found that success in kindergarten “highly correlated” with outcomes such as earnings at age 27, college attendance, home ownership and retirement savings.

But the quality of the early education experience also mattered, the study found. Students in small classes were significantly more likely to attend college. Students with a more experienced teacher in kindergarten had higher income later in life.

Another study found that, after accounting for poverty, Latino and white children learned math at the same rate during kindergarten. Although the study also concluded that kindergarten was not enough because, as a group, Latino children started behind their white peers, and therefore they remained behind in math by the spring of the kindergarten year. Attending full-day kindergarten was an important strategy in helping disadvantaged children become successful academically, the study concluded.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.