Sacramento likely can’t force L.A. City Council reform. It’s trying anyway

- Share via

In response to the city’s audio leak scandal, a proposed state law could force Los Angeles to establish an independent redistricting commission, curtailing the City Council’s influence over the lines that delineate their districts.

State Sen. María Elena Durazo, who introduced the bill Monday along with a coalition of Los Angeles-area lawmakers, cited the incendiary recording involving three council members reported on by The Times in October, saying public confidence in the city’s redistricting process had eroded.

“The system is just not working the way that it should,” she said. “The City Council members should not control the process of how the boundaries are written.”

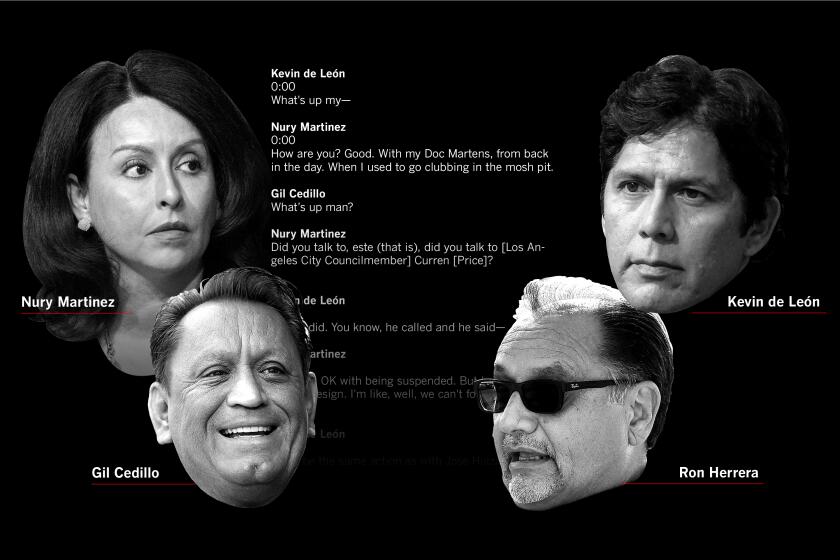

The leak — which revealed the City Council members and a prominent labor leader jockeying for favorable districts for themselves and their allies during an October 2021 conversation peppered with racist and derogatory comments — upended municipal politics and put a national spotlight on the city’s once-every-10-years redistricting process.

Even if the proposed law were to pass, it’s not clear whether the state has the power to dictate reform on the city level.

A bombshell recording has thrown L.A. politics into chaos. What was really being discussed? L.A. Times reporters and columnists pick it apart, line by line.

Under the current system laid out in the City Charter, city elected officials appoint members to the redistricting panel, who can essentially act as their proxies. The council has final say over approving the maps.

An independent commission would take that power away from the council, with the district maps being adopted by the panel and filed with a city elections official.

But changes to the charter — the civic constitution that governs Los Angeles — require a public vote. Experts say it’s likely that could still be required, even if the proposed state bill is successful.

Electoral boundaries are redrawn every decade in districts across the U.S. following the census, though Los Angeles’ contentious redistricting system is relatively new.

For much of the last century, council members were directly responsible for drawing the districts themselves. Sweeping change came in 1999, when Angelenos voted on a new version of the city’s 74-year-old governing document. The revised charter featured a compromise of sorts on redistricting, creating the current quasi-independent system of appointed commissioners.

UC Berkeley School of Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky, who chaired the city’s elected charter reform commission in 1999, said he thought the new proposal was a great idea, noting his commission had initially proposed an independent redistricting panel before the current structure was created.

But Chemerinsky had serious doubts about whether the change could be made unilaterally by state law.

“My sense is that it would require a charter amendment,” Chemerinsky said via email.

The overlapping layers of local government in California are the source of much confusion. Here’s an explanation of the various pieces.

State lawmakers successfully forced Los Angeles County to adopt independent redistricting, with a commission drawing supervisorial boundaries for the first time in 2021. That commission was created by a state law passed in 2016. The county then sued, claiming that a law targeting only one county violated the state Constitution, but lost on appeal in 2020.

But city and county governments have different relationships to state law, meaning the county ruling doesn’t necessarily set a precedent for a future scenario involving the city.

“City charters have a stronger impact in discussions with the state than county charters do,” local governance expert Raphael Sonenshein said — adding that conflicts between state law and city charters are where things “get interesting” and often wind up in court.

The California Constitution dictates that charter cities like Los Angeles have power over their “municipal affairs,” so the question for a hypothetical future legal battle would center around whether the redistricting of council boundaries is a municipal affair or a matter of state interest.

Both Sonenshein and Chemerinsky said that local elections have traditionally been viewed as municipal affairs.

“I see the argument on the other side — a state interest in independent districting commissions. But as I read this, it is about districting in Los Angeles,” Chemerinsky said via email. “That seems very much to be a ‘municipal affair.’”

The city of Los Angeles lets elected officials draw the lines of their own districts in the decennial redistricting process. That’s why “asset gerrymandering” is a thing in L.A.

Redistricting reform has gained steam in recent years, with Californians voting in 2008 to strip the Legislature of the power to draw its own districts and implement independent redistricting at the state level.

“Nationally, we have seen a number of states adopt independent redistricting commission models,” said Sara Sadhwani, an assistant professor of politics at Pomona College who served on the state’s redistricting commission.

Sadhwani said that advocacy groups like Common Cause and the League of Women Voters have “played a really important role in advancing the concept of independent commissions” from the perspective of transparency and good governance.

Paul Mitchell, an expert who has done over 100 municipal redistrictings, said he thought the text of the proposed state measure looked strong and noted that it appeared similar to the language used for independent redistricting commissions in Los Angeles County and the city of Long Beach.

The City Hall leak supercharged redistricting reform efforts locally, but a separate effort to remake the system began working its way through the L.A. City Council well before the tape became public.

Learn who to talk to in government when you want to get things done in your neighborhood. Get involved in your L.A. County community with the help of our people’s guide to power.

In December 2021, Councilmembers Nithya Raman and Paul Krekorian introduced a motion to begin the process of creating an independent redistricting commission for the city.

When the proposal came before the full council for a vote nearly a year later in late October, Raman sharply critiqued the amount of time it had spent languishing in a committee.

“This moment for change was here long before those tapes leaked,” Raman said.

Durazo, the Los Angeles Democrat who introduced the legislation, said the City Council has “had years to address this if they wanted to,” adding that she didn’t intend to leave the matter “in the hands of the City Council members.”

Chief Legislative Analyst Sharon Tso said via email that her office didn’t have a definitive answer to the question of whether the legislation would require a charter amendment “because, ultimately, it will be subject to legal interpretation if the bill is enacted.” Tso also noted that the bill “would be in conflict” with the reform proposals currently being considered at the city level.

“Regardless of any State bills, a Charter amendment would still be important, because legislation can be repealed by the very next legislature,” Rob Wilcox, a spokesperson for the city attorney’s office, said in an email. “By contrast, a Charter amendment requires voters to overturn it.”

Times staff writer Hannah Wiley contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.