How an L.A. grifter ripped off his best friends and got rich with his sprawling weed scams

- Share via

During his brief stint as a film actor in Manila, David Bunevacz played a sexy kidnapper named Johnny in a rollicking crime escapade, “Tusong Twosome.”

In one scene, he lounges in bed with a woman in his arms as he haggles over ransom on the phone.

“Honey, they have 10 million to give us,” Johnny tells her. “What do you think?”

“Ten million?” she scoffs. “That’s peanuts. I want my 20 million.”

“Honey, 10 million is a lot of money,” he insists.

Acting, it turned out, was not Bunevacz’s calling; he abandoned show business in the Philippines soon after the movie’s 2001 release.

But Johnny’s pillow talk foreshadowed the brazen life of crime Bunevacz went on to lead back home in Los Angeles, where he put his charisma to work in swindles that made him tens of millions of dollars.

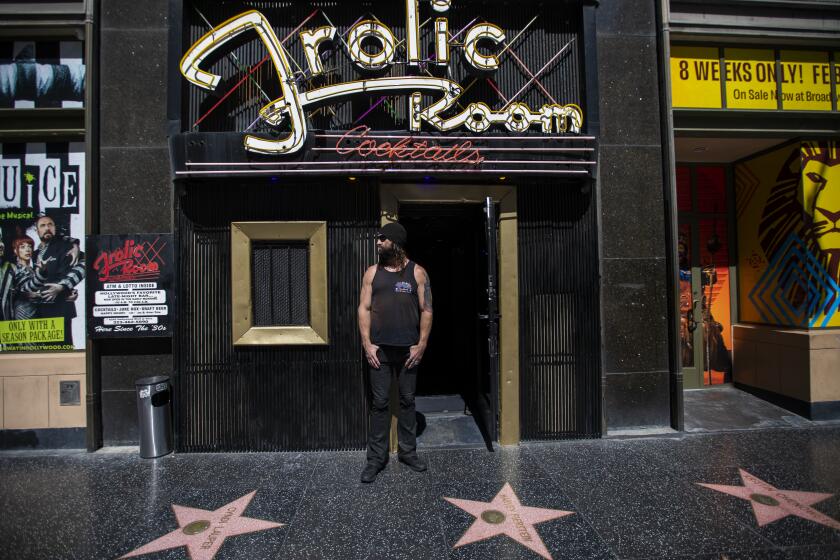

For more than a decade, Bunevacz, now 54, posed as a weed mogul cashing in on California’s booming marijuana trade.

With his self-confidence and gregariousness, he disarmed a long line of marks, dazzling them with stories of how they too could make a fortune in pot. A self-styled expert in psychology, he gauged their vulnerabilities and exploited them with devastating success.

Forging documents to make Holy Smokes Holdings LLC and other fake businesses look real, Bunevacz fleeced more than 100 people, including some of his best friends, a federal judge found. He ripped off his own dentist.

The loot fueled a lifestyle of boundless extravagance, richly detailed in court filings. Bunevacz tooled around L.A. in a yellow Lamborghini Urus. His wife, Jessica R. Bunevacz, author of the cheeky self-published “Date Like a Girl, Marry Like a Woman,” drove a Bentley.

The family weathered much of the COVID-19 pandemic in a Calabasas mansion that was once home to Kylie Jenner. Monthly rent was $18,000.

The ostentation itself was bait, making his victims even more eager to get in on the deals that seemed to be making Bunevacz so rich.

To celebrate the 16th birthday of his youngest daughter, Breanna, Bunevacz threw a $218,000 party featuring rapper A Boogie wit da Hoodie at the Skirball Cultural Center in Brentwood.

He also bought her a $330,000 horse named Vondel, a Bay Zangersheide gelding, to ride in equestrian contests. He immersed himself in the world of teenage horse enthusiasts, befriending well-to-do parents and charming them into ill-fated wagers on his vape pens.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“Like any good businessman, he found a market for his scams,” said Bill Sewell, who got close to Bunevacz at horse shows and said he wound up cheated out of $50,000. “If your goal is to steal money from people, you want to steal money from wealthy people, and you have to buy in and live that lifestyle so you’re living it as a native, not as a tourist.”

Even in Bunevacz’s upscale social circles, the flashiness stood out. He and Jessica sometimes chartered yachts and private jets and once paid for friends’ suites at the resort in the Bahamas where they renewed their wedding vows. When they entertained in Calabasas, guests who walked by the show cars parked out front pondered the lurid possibilities of the wealth’s origins, but kept their musings to themselves.

Bunevacz repaid a handful of early investors in his weed enterprise with a decent return, typically 10% to 15%. Impressed, they lent still more to the shell companies he was siphoning for himself, his wife and their three children. Most investors got nothing back. A few lost their life savings.

The ruthlessness paid off, but also left many angry victims hounding him to retrieve their money. One of the bilked investors, according to a lawyer who spent years hunting for stolen proceeds, was so enraged that he grabbed Bunevacz and put him in a headlock.

The son of immigrants from opposite sides of the world, Bunevacz grew up in the L.A. suburbs — the South Bay and Palmdale.

His mother, Filomena, was a young nurse when she moved from the Philippines to California in the late ‘60s. She fell in love with Joseph Bunevacz, a Hungarian in the restaurant business. They married, bought a two-bedroom house in Redondo Beach and had two kids, David and his younger sister, Desiree.

David emerged as a star athlete in high school. At track meets, he won first place in high hurdles and high jump. At UCLA, he was a champion javelin thrower.

L.A. couple facing prison for stealing $18 million in a pandemic relief scam took a private jet to the Balkans and vanished into a posh town on the Mediterranean.

Bunevacz (pronounced boon-eh-vahtch) went on to compete for the Philippines at the Southeast Asian Games in 1997, placing second in the decathlon.

After some minor brushes with the law in L.A. (he and his friends had fun shoplifting clothes, he would later testify), Bunevacz settled for a time in Manila, where he met Jessica Rodriguez, the actor, model and talent manager he would marry.

He found gigs appearing in commercials and broke into the country’s thriving entertainment industry — co-hosting a sports and travel TV show and landing a couple film parts.

His biggest role was in “Tusong Twosome.” At the end, Johnny gets beaten up in a warehouse, then blown to bits by a car bomb.

Around 2006, Bunevacz launched a cosmetic surgery clinic called Beverly Hills 6750 in an upscale Manila office tower. Its billboard slogan promised dramatic makeovers for romance seekers: “Miss Ugly No More.”

“It was a business that my wife wanted to put up,” Bunevacz explained years later.

In a sign of things to come, board members and investors soon accused Bunevacz of misusing clinic funds to fly first-class to California and buy luxury cars, according to civil lawsuits and Filipino press reports.

One of the cars was a BMW X5 that he gave his wife after she sang on the popular “Celebrity Duets” TV show. Jessica wept when she saw the big red ribbon taped to the SUV’s hood.

Bunevacz was later roughed up, threatened at gunpoint and forced to sign over his Porsche Cayenne Turbo, according to the celebrity press in Manila and a friend in California who heard him tell a version of the story that featured him leaping out a second-story window to flee. “A little mixture of ‘Jason Bourne’ and ‘Indiana Jones,’” the friend recalled.

Bunevacz testified that his business partners kidnapped him for three hours and left him “beat up pretty bad” before he finally escaped.

“I ran down the street, I got in a taxi all bloodied up,” he said.

He and his family quickly packed their belongings and left the Philippines for good, resettling at his parents’ place in Palmdale.

Bunevacz resurfaced in Asia at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, where he set in motion an audacious ticket scam.

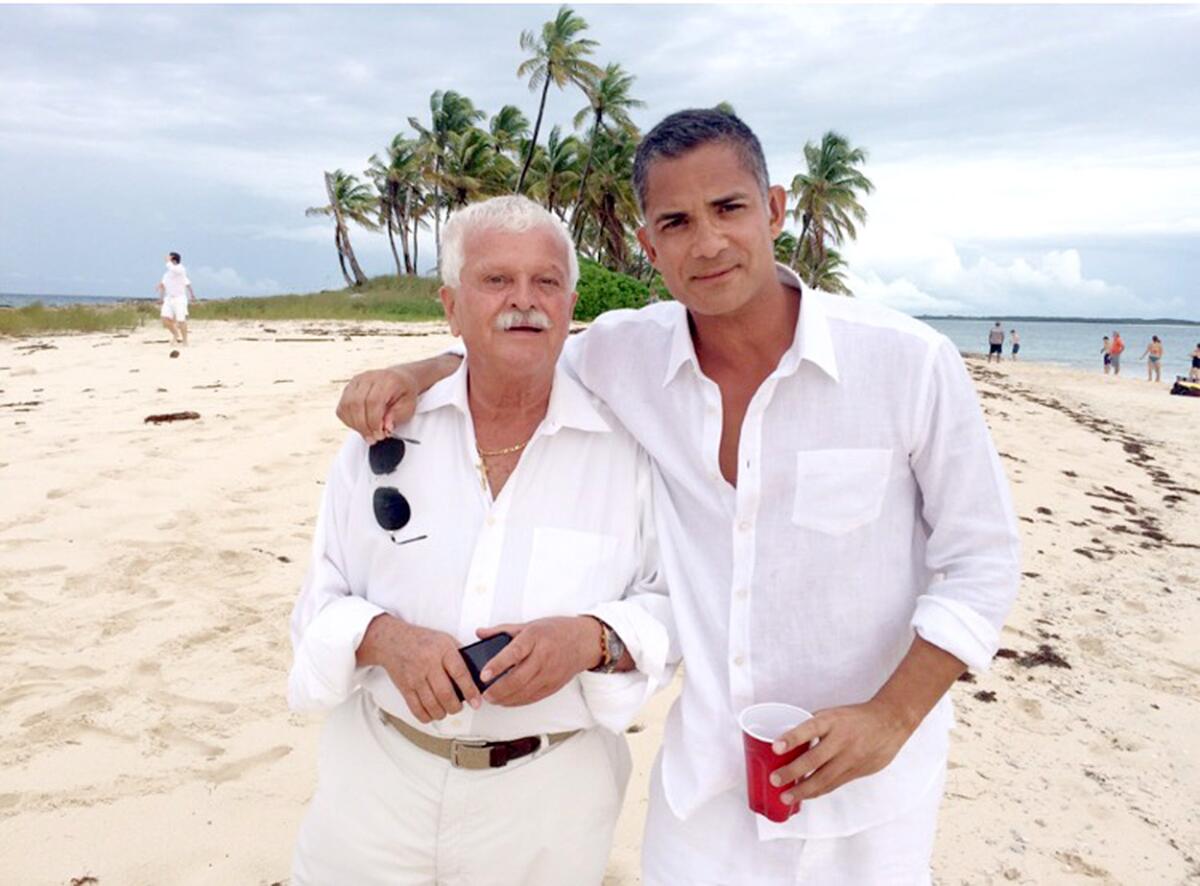

The deal seemed legitimate at first. His dad, Joseph Bunevacz, was working on travel and logistics with the Hungary and Spain national Olympics committees, giving him access to tickets that he and his son could sell.

The two of them met Gene Hammett, an Atlanta ticket broker, at a Beijing hotel. David took Hammett to a room with batches of tickets to various Olympics events over the next two weeks, Hammett said in an interview.

Hammett bought about 2,000 tickets and resold them at a markup, turning a quick profit of more than $300,000. He liked Bunevacz.

“We had a good relationship, and everything worked smoothly, and he was very connected,” Hammett recalled.

Bunevacz invited Hammett to join him in his suite at the Bird’s Nest stadium for track-and-field events; they watched Usain Bolt of Jamaica break a world record in the 100-meter sprint.

A Hollywood woman is accused of hiring a TV actor to deliver the fentanyl-laced drugs that killed a Beverly Hills man.

With such trappings of legitimacy, Bunevacz lured Hammett into the con that would upend his life: He told him his connections could again supply tickets to the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver. Hammett agreed to buy 17,000 tickets.

“I trusted him,” Hammett recalled later in court. “He called me his brother. He prayed with me. And so I got into the biggest deal of my life with him, and that was … when everything fell apart.”

Hammett made $2.9 million in payments to Bunevacz over the next 18 months, but never received a single ticket.

To string Hammett along, Bunevacz later admitted in court, he forged a document to make it look like he’d paid a Hungarian supplier more than $700,000 for Vancouver event tickets.

David Bunevacz is questioned by James R. Moriarty, an attorney for Gene Hammett, in a November 2010 deposition.

Bunevacz even charged Hammett $73,000 for a “VIP Trip” that he claimed Hungarian officials took to Canada, his lawyers asserted in court: plane tickets and nine rooms at Four Seasons hotels in Whistler and Vancouver, “spa treatments, food, car rentals, mini bar and souvenirs.”

It was actually Bunevacz and his father enjoying the posh resorts, the lawyers alleged.

Stranded in Vancouver with no tickets, Hammett’s customers were livid. Some sued him, and Hammett was ultimately driven into bankruptcy and lost his home.

Bank records that surfaced in court years later laid bare how shamelessly Bunevacz had pilfered Hammett’s 35 wire transfers.

‘Wall Street Whiz Kid’ David Bloom allegedly attempted to turn dozens of L.A. luxury apartment dwellers into his newest set of marks.

The money found its way to Tiffany, Bloomingdale’s, Neiman Marcus, Giorgio Armani and Hermès, along with a Ritz-Carlton spa in Georgia and the Bacara resort in Santa Barbara, Hammett’s lawyer Filippo Marchino discovered.

“He was just burning money as soon as he got it,” said Damon Rogers, another Hammett attorney.

Most striking were the quick shifts of Hammett’s money to Bunevacz’s players account at the Bellagio in Las Vegas — in one case $125,000 a week before the family’s annual New Year’s holiday at the casino resort.

Hammett ultimately sued Bunevacz, who agreed in a settlement more than four years later to pay him just $325,000.

Hammett also sued Joseph Bunevacz, but the case was dismissed with no finding of wrongdoing. The father recently hung up on a Times reporter seeking comment.

“I looked at myself as smart,” Hammett said. “But being scammed by someone who took me for this money, it was really hard for me.”

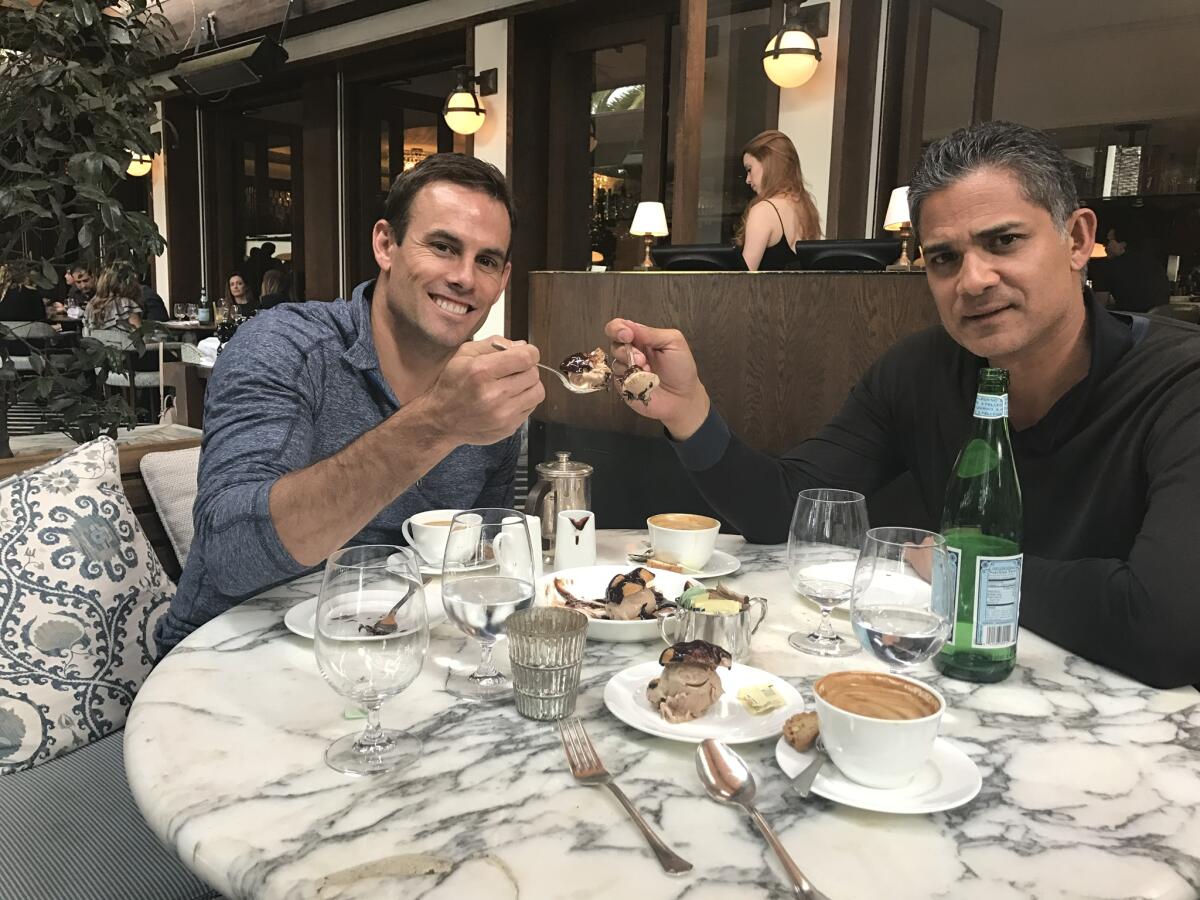

Tom Danford was resting in the pool during a swim workout at the Paseo Club in Santa Clarita in 2015 when David Bunevacz made his fateful pitch: “I’d love to run an idea by you — an investment opportunity.”

They’d become good buddies over the past year. Danford’s wife, Meredith, had met David and Jessica in a Pilates class and introduced them to Tom at a mixer. The two couples hit it off.

The Bunevaczs had recently settled in Santa Clarita, where they formed a tight-knit group of friends with the Danfords and a few other couples and their kids. The families enjoyed frequent backyard barbecues. They spent birthdays and holidays together in Mammoth, Palm Springs and Santa Barbara.

The Danfords went to church with the Bunevaczs. They traveled to Breanna’s equestrian contests to show support. And Tom flew to New York with David when Breanna and Jessica were featured in Lifetime’s “Making a Model with Yolanda Hadid.”

Their social group included a Backstreet Boys pop star and his wife, but the spending habits of David and Jessica Bunevacz were much more conspicuous, the Danfords said in an interview.

David shuffled through “all different types of Porsches,” Meredith recalled, and Jessica had “a ton of Hermès” and “jewelry out the wazoo.”

Tom Danford remembered the jaw-dropping display of some 50 pairs of high-end shoes in Jessica’s closet. “It was absurd,” he said. “The amount of bags — $30,000 bags, these, what are they called — Birkin bags.”

In an email, Jessica described herself as a “victim” of her husband’s crimes, but declined to be interviewed.

When Bunevacz casually suggested an investment deal during the swim practice, Danford agreed to chat afterward. Over banana-chocolate protein drinks, Bunevacz explained how it would work.

He claimed to be buying empty vape pens in China, exporting them to the U.S., filling them with cannabis oil and selling them.

If Danford put up $30,000 for a shipment from China, Bunevacz promised, he would repay it with interest once the vape pens were sold.

Danford, a web entrepreneur, was drawn to risky bets and trusted his friend, who was clearly a successful businessman. He was in. Two months later, he got his money back with a 12% return.

“Hey, this is great,” Danford recalled telling Bunevacz. “I’d be open to some more.”

He did it a second time. It worked again.

Bunevacz then proposed a partnership in Holy Smokes, a company he claimed to be worth $4 million. Danford could take a 5% stake for “200 grand.” In return, Bunevacz would pay quarterly dividends. Danford thought he could use the money for property taxes or his family’s Christmas.

He cashed in much of the family’s savings to do it. “Because I’m like, this makes sense,” he said. “I don’t see why it doesn’t. And 8% is boring, you know? The slow and steady route is boring. And this is an emerging industry.”

But Bunevacz failed to pay.

“I’m like, ‘Dude, don’t do this,’” Danford recalled thinking.

The men were close, so it was uncomfortable to complain and get “every slick excuse in the world,” Danford said.

Fed up, he asked for his money back. “I’m not comfortable with the direction of this business, and I don’t want to be involved in it any longer,” he said he told Bunevacz.

“Lawyer up, buddy,” Bunevacz responded.

“That’s when the teeth came out,” Danford said.

By then, Bunevacz had ensnared dozens of other victims into variations of his weed scam, court records filed by prosecutors show. As investors in Texas, Florida, New York and other states came to realize they’d been taken, it got harder to cover up the fraud. They started winning millions of dollars in civil judgments against him.

They also reported Bunevacz to local police, the FBI, the Secret Service and the Postal Inspection Service.

In August 2016, the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department arrested Bunevacz on grand theft and other state charges after two disgruntled investors filed complaints.

He quietly disposed of the case by pleading guilty to two securities felonies and paying the victims $785,000 in restitution — money he got by dipping into funds he had stolen from other investors, a federal judge would later find. His 360-day jail sentence was suspended.

Unabashed, Bunevacz stepped up the hustling, cajoling victims into wiring him millions of dollars more. In some cases, he created companies with names that were nearly identical to successful businesses, including Grenco Science, a vape-pen outfit known for its Snoop Dogg G Pen.

Geoffrey Elliott, a Sheriff’s Department detective on a fraud team in Chatsworth, opened a new investigation. From reviewing nearly a dozen Bunevacz bank accounts, it was clear to Elliott that he was not really buying vape pens in China.

At jewelry stores in Beverly Hills, the detective told a judge, Bunevacz used investor money to buy diamond earrings for $209,500; a diamond ring for $195,000; a Rolex Submariner watch for $14,215; and three bracelets and two Hermès Birkin bags — one in cream, the other in bleu Zanzibar and green — for $46,500.

Vondel, the $330,000 horse, turned out to be just a fraction of the $1.3 million that Bunevacz spent on Breanna’s equestrian pursuits.

And his latest Porsche convertible, a $166,000 911 Turbo S, was costing Bunevacz $4,075 a month to lease; he stopped making payments after 11 months, prompting a repossession, according to a lawsuit filed by Porsche affiliates.

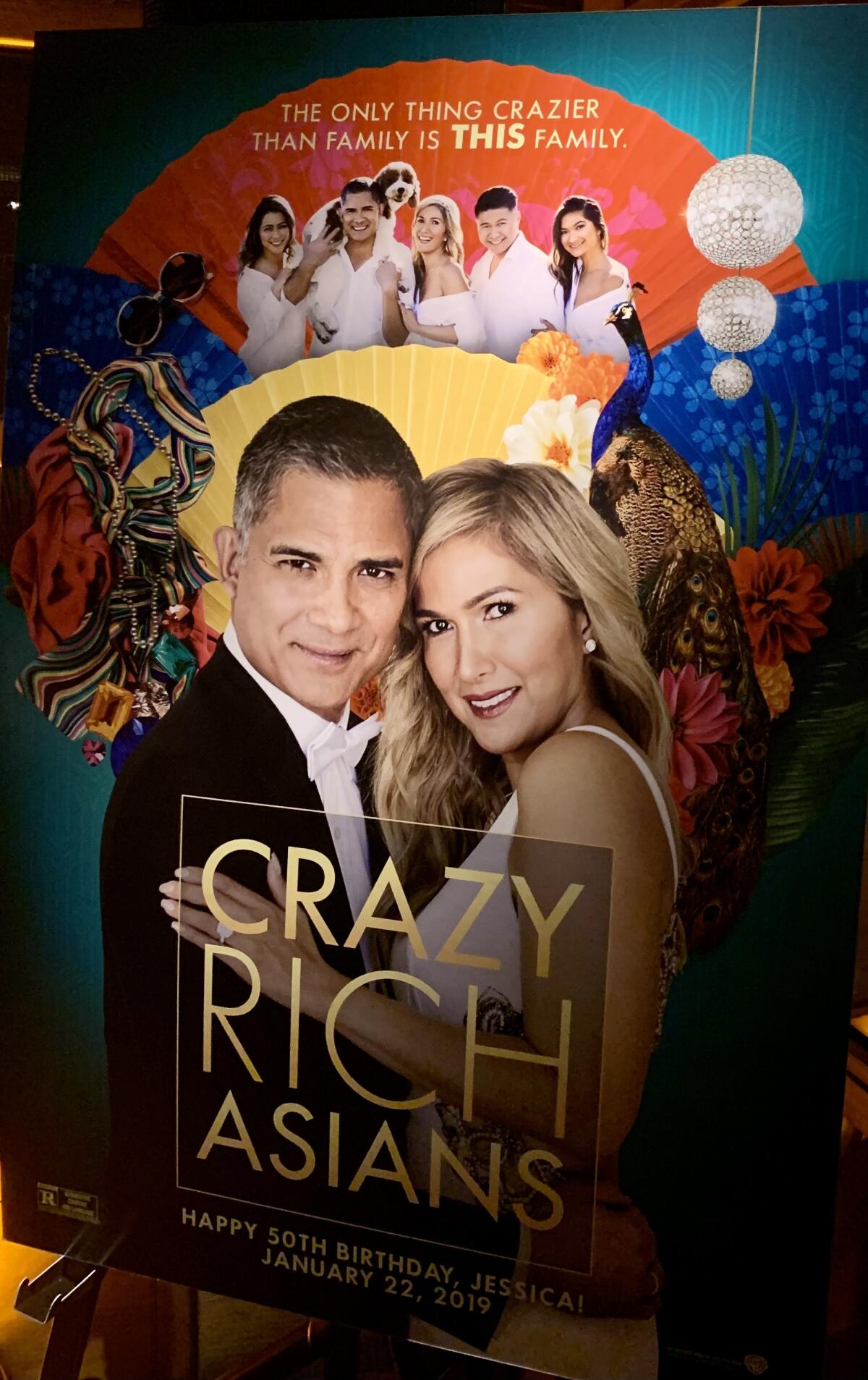

Bunevacz also squandered $8 million at the Wynn and other Las Vegas resorts, Elliott told the court, and the family’s credit card charges exceeded $11 million. A 50th birthday holiday for Jessica at the Montage in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, cost $65,000.

In the midst of all that spending, the couple made it all but impossible for creditors to collect on their judgments.

In February 2020, lawyers for a Florida investor whose $4-million vape-pen deal ran aground grilled Jessica and David Bunevacz about where their money came from.

Jessica, who hosts “The Polished Woman,” an online talk show with 391 YouTube subscribers, claimed her brother in the Philippines sometimes drew from the pesos she stashed there to send her U.S. dollars in cash.

“Is it in a vault held by your family?” attorney Sean Bigley asked her. “Is it in gold bars?”

“My country is a Third World country,” she explained. “We don’t really put them in the bank.”

Asked how much money she had, she said, “I just don’t remember.”

Her husband’s deposition was no more fruitful. “Did you use any of my client’s money for gambling?” Bigley’s law partner Jeremy Gray asked.

“I don’t recall,” David Bunevacz replied.

“Did you use any of my client’s money for vacations?”

“I don’t recall.”

How about watches? “I don’t wear a watch. I never have.”

Months later, Elliott, who served on an FBI task force, got a search warrant to raid the Calabasas mansion, where detectives seized reams of documents they could use to prosecute Bunevacz. The FBI, Internal Revenue Service, and Securities and Exchange Commission joined the investigation.

In his request for an arrest warrant a year later, Elliott called Bunevacz a “peripatetic grifter” who forged financial records in layers and layers of schemes to steal millions of dollars.

In July, Bunevacz pleaded guilty to federal securities and wire fraud charges, admitting he stole as much as $35 million.

Efforts to interview Bunevacz in prison were unsuccessful, and his criminal lawyer, James S. Threatt, did not respond to a request for comment.

“Mr. Bunevacz, is there anything you would like to say?” U.S. District Judge Dale S. Fischer asked him at his sentencing in November.

“No, your honor,” Bunevacz, wearing a beige jail jumpsuit, told her.

Fischer invited his victims to speak. Hammett told her that Bunevacz “pillaged people who would fall prey to his charm.” Then Danford stepped up to the lectern and let loose.

“David and Jessica knew my family intimately,” he told the judge.

Recalling private conversations about him and Meredith struggling long ago to overcome substance abuse, he said David and Jessica knew their recovery and family were “the most important thing[s] in our lives next to our faith.”

“They preyed on that knowledge, and they manipulated us from the beginning of the relationship while pretending to care about us and the well-being of our children,” Tom said.

Looking back on the prayer groups that David and Jessica used to convene at their house, he added, “It was just another ruse to keep people believing that they were this morally centered family that truly cared about others and had a deep faith in Christ.”

Next came the dentist, who was tricked out of $800,000.

“Sorry, hands are shaking,” the dentist told Fischer. He remembered Bunevacz saying he could buy his parents a house with his earnings on the vape-pen deal. Expressing dismay at the “coldheartedness,” he suggested Bunevacz could be “sociopathic.”

“I think he’s a different level of crook,” he said.

Assistant U.S. Atty. Alexander Schwab recommended 11 years and three months in prison. Fischer decided Bunevacz deserved more.

“His purpose was to provide himself and his family with an extremely extravagant lifestyle, which they flaunted on social media,” she said.

She sentenced Bunevacz to 17 years and six months in prison. She also ordered him to pay victims $35 million in restitution, conceding it was unlikely he ever would.

Bunevacz had told her in a letter that he was “extremely sorry and will never forget the trail of damage I have left behind.” Fischer dismissed it as “probably the least convincing letter the court has ever received from a defendant.”

“I am not in the least persuaded,” she said, “that Mr. Bunevacz regrets anything other than he was caught.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.