He was making a documentary about police brutality. Then the LAPD tased him in his home

- Share via

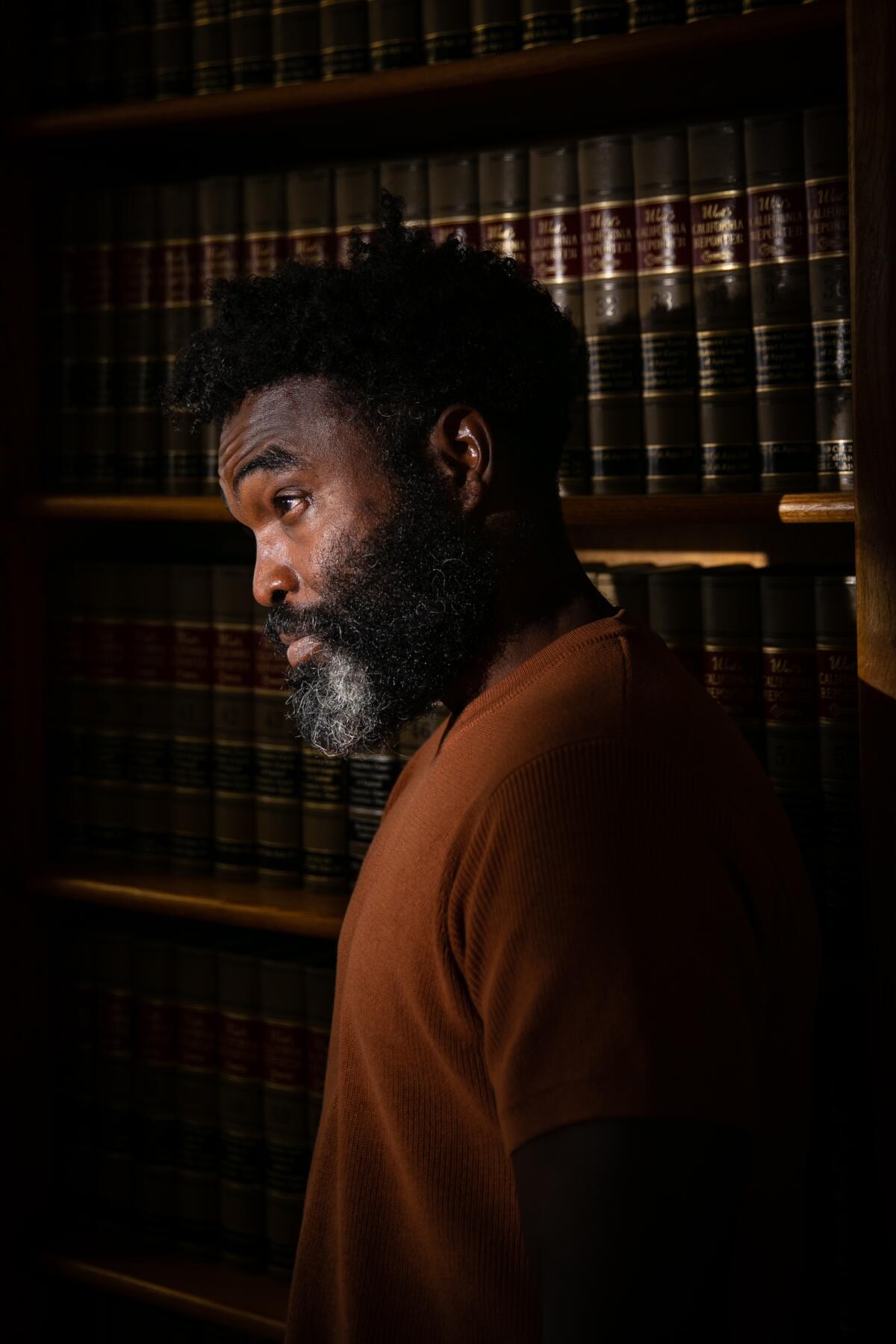

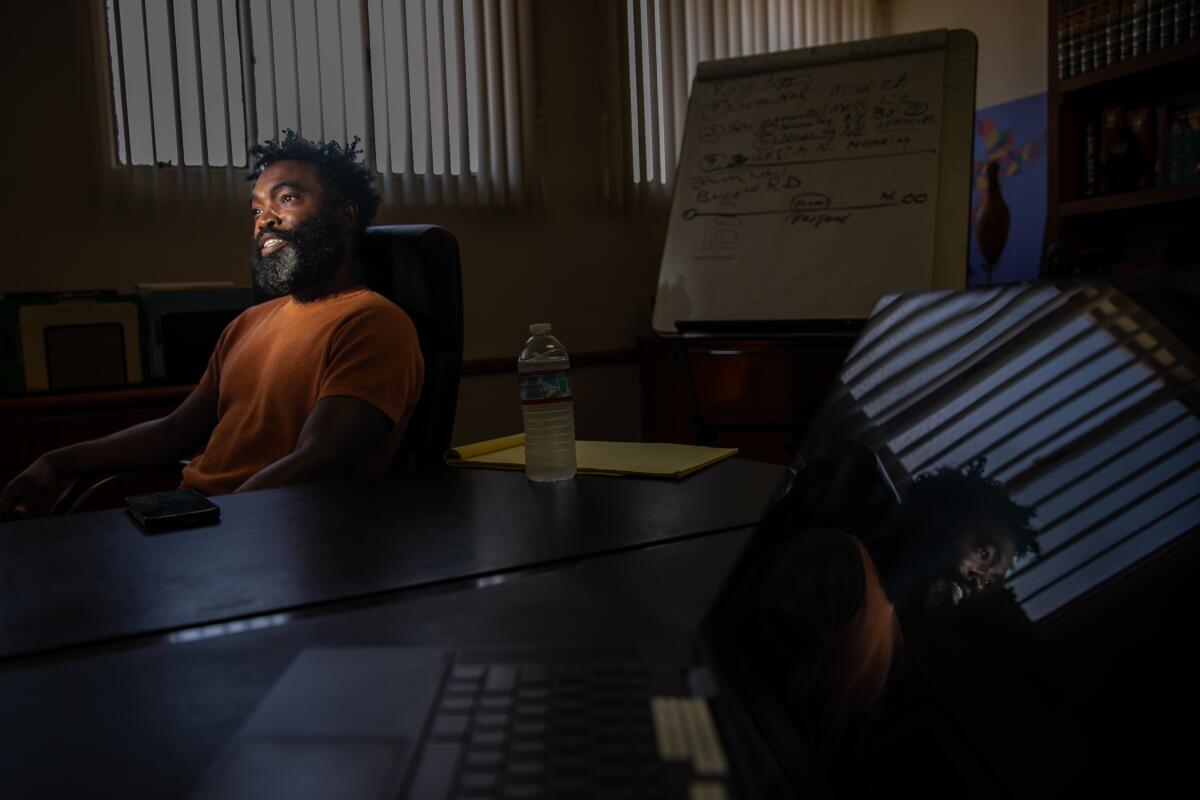

Damien Smith was making a documentary about police brutality. But when a burglar broke into his Hollywood apartment, he didn’t hesitate to call the cops.

Smith, a filmmaker and actor, was critical of law enforcement but believed officers were necessary to fight crime. He hoped for better community policing. That was the subject of his documentary, “Searching for Officer Friendly,” which focuses on national policing trends and the militarization of police forces.

But Smith says when police arrived at his home late at night, officers tased him — not the burglar. They then placed him in the back of a squad car. He was released not long after, but not before being humiliated in front of his neighbors.

He has now filed a civil lawsuit against the Los Angeles Police Department.

“I’m still in shock and awe of how this transpired,” Smith said. “I’m in such fear of calling the police. … Look what happened to me.”

The LAPD provided little information about the incident, so the narrative comes from Smith and his neighbor, who witnessed part of the encounter.

Police did not open an investigation until Smith sued in June — more than a year after the incident, an LAPD spokesman told The Times. Officials did not comment further and declined to release body camera footage.

“At this time, there is no statement,” Officer Drake Madison said.

The “Snowfall” actor had returned to his McCadden Place home around 12:30 a.m. on Oct. 14, 2021, according to his lawsuit. About to leave town and expecting a friend who would drive him to LAX, Smith was confronted by a stranger carrying a backpack and wearing his grandfather’s watch.

The man, who was exiting the bedroom, claimed to be a mover, said Smith, who grabbed a camping knife and sliced the man’s hand when he charged. After the attack, the man lay on the floor and complied with orders. Smith then called police.

The friend who was supposed to drive him to the airport arrived while he waited for police, Smith said. She did not respond to requests from The Times for comment.

Officers arrived at Smith’s apartment around 1:30 a.m. and approached from his street-facing back door, which was ajar, according to the lawsuit. They had what looked like guns pointed at Smith, who was still holding the camping knife and standing above the burglary suspect. When officers told him to put down the knife, he did, Smith said.

“I dropped it,” he said. “I complied to what the officers are telling me to do.”

While the officers were shouting commands at Smith, frightened neighbors tried to explain.

Tiffany Wysinger, who lives in the apartment above Smith’s, said she was roused from sleep by the commotion. When she realized where the noise was coming from, she ran downstairs.

“Police were there. I was screaming at the top of my lungs,” she said. “I see them with something drawn, and I scream at the top of my lungs, ‘He’s the resident!’ ”

Smith said he was about 10 feet away from the officers, who did not immediately enter his apartment.

“I live here. I called 911,” Smith repeatedly told police, who were commanding him to get on the ground, according to the lawsuit.

Wysinger said she continued to scream that they were targeting the homeowner, not the burglar, who was still lying on the ground.

“Then I hear a pop, and I start crying profusely thinking they killed Damien,” she said.

Bernard Robins, who was detained outside his parents’ South L.A. home by fellow LAPD officers, said the episode typifies the style of biased policing that’s practiced in some parts of the city.

Smith crumpled to the floor. Police tased him twice more, according to his suit. The bursts of electricity shot through him over and over. He said he thought it would never stop.

With Smith no longer standing over him, the burglar jumped up and ran to the bedroom.

Only after tasing Smith did officers enter his apartment, the lawsuit claims. They handcuffed Smith, walked him out of the house in front of his neighbors and put him in the back of a police car.

“I’m like, ‘I’m the one who called you.’ They’re like, ‘Shut up,’ speaking to me very disrespectfully,” Smith said.

Smith sat in the patrol car for about 15 minutes while police interrogated him, he said. It was not until an emergency medical technician asked for his ID that officers conceded Smith lived in the apartment.

Soon after, a captain ordered Smith to be taken out of the squad car and his handcuffs removed, he said.

“No one apologized,” Smith said.

A man named Demani Coats was arrested at Smith’s apartment. He was convicted of burglary after pleading no contest in July 2022.

Smith was not arrested or charged with any crime.

Eight months after The Times revealed racist texts by Torrance police officers, city officials have done little to hold them accountable.

Smith’s lawsuit targets the department and the officers involved in the incident, claiming the LAPD violated his civil rights and subjected him to false arrest and imprisonment.

Only one officer was identified in the complaint, by his last name and badge number. The Times found through LAPD records the badge number belongs to Leovardo Guillen.

In the lawsuit, Guillen and other unnamed officers are accused of tasing Smith “approximately three times.”

Ed Obayashi, an expert who investigates use of force incidents for California law enforcement departments, said that until body camera footage is released, it will be difficult to determine whether the police acted out of policy.

“If the officers can’t articulate that there was an immediate threat to their safety or others, then it’s a bad tasing — period,” Obayashi said. “But on the other hand, if the guy got belligerent or came at the officers and officers reasonably believed this guy was going to fight or had something in his hands ... then it would be a justifiable use of force.”

Black Americans are especially pessimistic that any more progress on racial equity will be made in the coming years, a poll finds.

Smith, who is Black, sees his race as a key component in the police’s decision to tase him.

“I believe there was a racial component to this whole situation, how the police treated me, how everything was executed,” he said. “I don’t think it would have went down in this manner if I was not African American.”

Milton Grimes, Smith’s attorney, said the interaction reflects why some Black people are hesitant to call police.

“They fear they will end up being the victim double. They are victim when they call, and now they are victim of police,” said Grimes, who also represented Rodney King after he was brutally beaten by four LAPD officers in 1991. “Too many times officers come with some attitude that escalates into violence.”

Smith said he is currently going to therapy and forging ahead in his career.

But making a documentary about police brutality is harder after being a victim of it, he said.

“To do a documentary about policing, you have to deal with policing, and I’m traumatized by dealing with police,” Smith said. “Right now, it is really hard.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.