California bans controversial ‘excited delirium’ diagnosis

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — California is the first state to ban doctors and medical examiners from attributing deaths to the controversial diagnosis known as “excited delirium,” which a human-rights activist hailed as a “watershed moment” that could make it harder for police to justify excessive force.

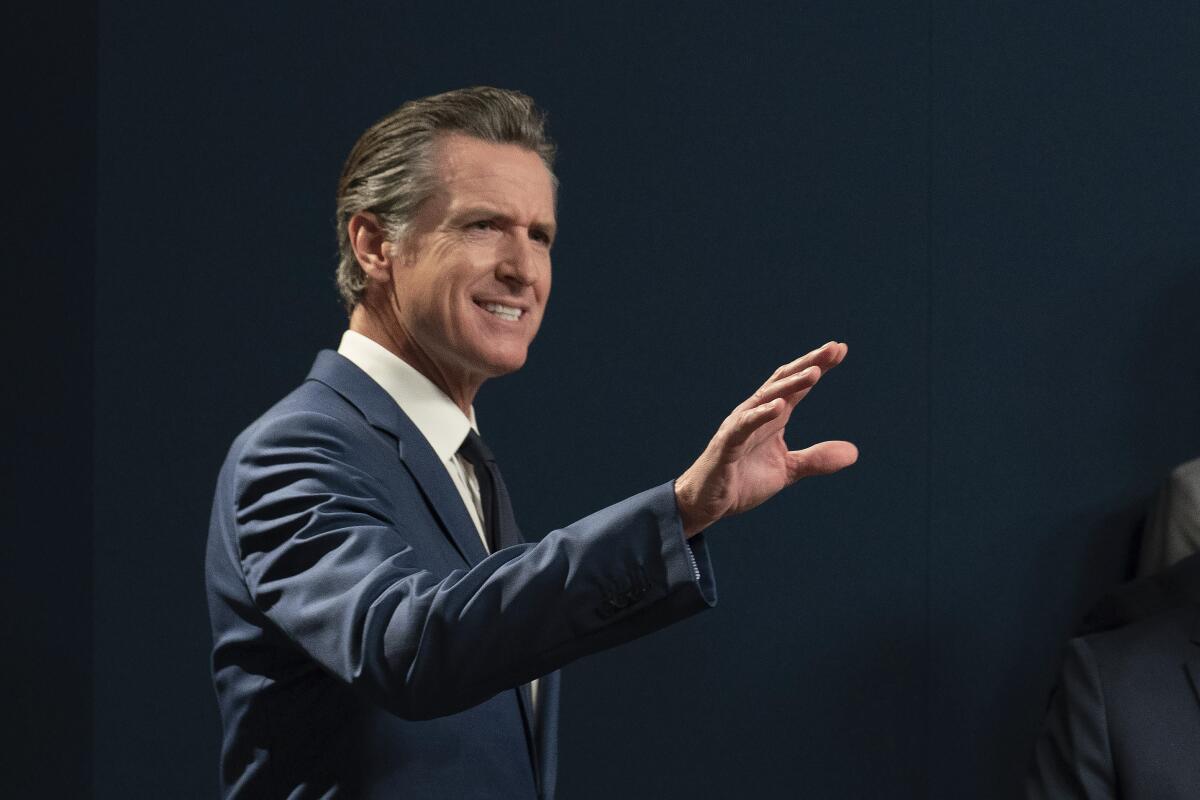

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill Oct. 8 to prohibit coroners, medical examiners, physicians or physician assistants from listing excited delirium on a person’s death certificate or in an autopsy report. Law enforcement won’t be allowed to use the term to describe a person’s behavior in any incident report, and testimony that refers to excited delirium won’t be allowed in civil court. The law takes effect in January.

The term excited delirium has been around for decades but has been used increasingly over the last 15 years to explain how a person experiencing severe agitation can die suddenly through no fault of the police. It was cited as a legal defense in the 2020 deaths of George Floyd in Minneapolis; Daniel Prude in Rochester, N.Y.; and Angelo Quinto in Antioch, Calif., among others.

“This is a watershed moment in California and nationwide,” said Joanna Naples-Mitchell, a lawyer with the New York-based Physicians for Human Rights, who co-authored a 2022 report on the use of the diagnosis.

“In a wrongful-death lawsuit, if excited delirium comes up, it’s a big hurdle for a family getting justice if their family member was actually killed by police,” Naples-Mitchell said. “So, now it will be basically impossible for them to offer testimony on excited delirium in California.”

The theory of excited delirium has exonerated law enforcement officers who killed people in their custody. But there’s mounting opposition to the term among most prominent medical groups.

Although the new law makes California the first state to no longer recognize excited delirium as a medical diagnosis, several national medical associations have already discredited it. Since 2020, the American Medical Assn. and the American Psychiatric Assn. have rejected excited delirium as a medical condition, noting that the term has disproportionately been applied to Black men in law enforcement custody. This year, the National Assn. of Medical Examiners rejected excited delirium as a cause of death, and the American College of Emergency Physicians is expected to vote this month on whether to formally disavow its 2009 position paper supporting excited delirium as a diagnosis. That white paper proposed that individuals in a mental health crisis, often under the influence of drugs or alcohol, can exhibit superhuman strength as police try to control them, and then die from the condition.

In the case of Quinto, his mother, Cassandra Quinto-Collins, had called Antioch police two days before Christmas because her son was experiencing a mental health crisis. She had subdued him by the time they arrived, she said, but officers held her 30-year-old son to the ground until he passed out.

In a harrowing home video taken by Quinto-Collins, which was broadcast nationally after his death, she asked police what happened as her son lay on the floor unconscious, hands behind his back in handcuffs. He died three days later in the hospital.

The Contra Costa County coroner’s office, part of the Sheriff’s Office, blamed Quinto’s death on excited delirium. The Quinto family has filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the county and is seeking to change the cause of death on his death certificate.

Quinto-Collins also testified in favor of the bill, AB 360, introduced by state Assemblymember Mike Gipson (D-Carson). It sailed through the Legislature with bipartisan support. No organization formally opposed the measure, including the California Police Chiefs Assn., whose executive director declined to comment this week.

“There’s a lot more work to be done, but it is a unique window into some of the corruption, some of the things that we’ve allowed to happen under our noses,” said Robert Collins, Quinto’s stepfather. “I think it’s really telling that California is ending it.”

Part of the problem with an excited delirium diagnosis is that delirium is a symptom of an underlying condition, medical professionals say. For example, delirium can be caused by old age, hospitalization, a major surgery, substance use, medication or infections, said Sarah Slocum, a psychiatrist in Exeter, N.H., who co-authored a review of excited delirium published in 2022.

“You wouldn’t just put ‘fever’ on someone’s death certificate,” Slocum said. “So, it’s difficult to then just put ‘excited delirium’ on there as a cause of death when there is something that’s underlying and driving it.”

In California, some entities already had restricted the use of excited delirium, such as the Bay Area Rapid Transit Police Department, which prohibits the term in its written reports and policy manual.

But these changes confront decades of conditioning among law enforcement and emergency medical personnel who have been taught that excited delirium is real and been trained in how to handle someone suspected of having it.

“There needs to be a systematic retraining,” said Abdul Nasser Rad, managing director of research and data at Campaign Zero, a nonprofit group that focuses on criminal-justice reform and helped draft the California law. “There’s real worry about just how officers are being trained, how EMS is being trained on the issue.”

KFF Health News, formerly known as Kaiser Health News, is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — an independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.