Newsom freed elderly and sick prisoners during COVID, but he’s grappling with risks of more mercy

- Share via

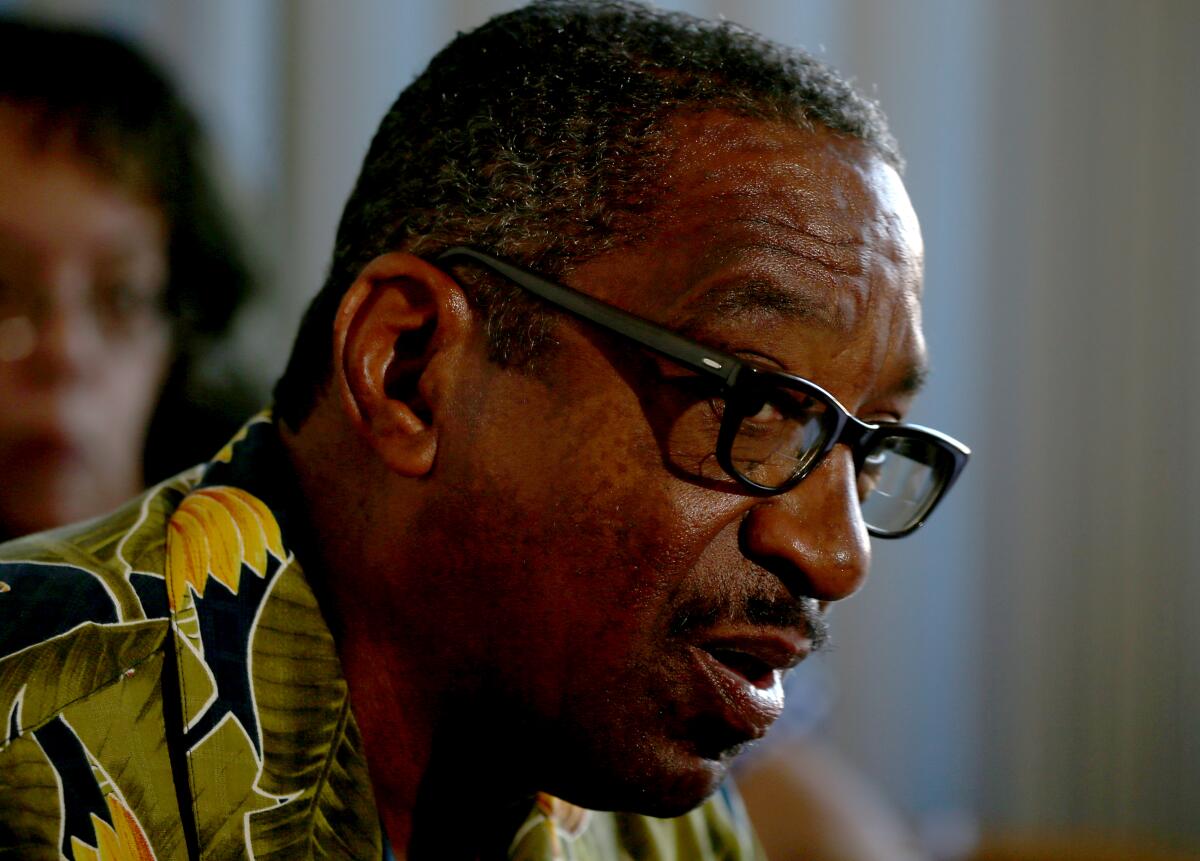

David Moreland had long expected to die in prison.

But when the coronavirus nearly killed him in 2020, it was that brush with death that ended up freeing him.

“This is how God works,” Moreland, 67, said from his cozy living room at a subsidized apartment complex for seniors in Long Beach.

When Moreland contracted COVID before vaccines were available, he said his oxygen levels were so low that a doctor was preparing to hook him to a ventilator. Handcuffed to a hospital bed and hot and delusional with a fever, he feared he would not survive.

Yet as the virus ravaged California’s overcrowded prisons Moreland recovered from respiratory failure and a blood clot in his lungs. After a month in the hospital, he had to relearn to walk with shackles on his feet.

Then, another “miracle” happened, Moreland said: A prison guard told him he had a call from Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office.

The governor had deemed Moreland a “high medical risk” and decided to release him from prison. After two decades behind bars for a robbery he says he did not commit, Moreland, who faced a potential life sentence, walked out in 2022.

He is among 35 prisoners Newsom has granted a “medical reprieve,” a form of clemency the Democratic governor created during the pandemic to show mercy for the sick and elderly. They were handpicked by the Newsom administration to access a new path to freedom that amounts to an experiment in California’s ongoing effort to shrink the prison population without compromising public safety.

But as the pandemic wanes and Newsom confronts the limited time he has left in office, the second-term governor is grappling with whether to extend the new form of clemency to more inmates. He’s signaling caution amid calls from advocates who want the emergency response to become a permanent policy of broader mercy for some who are hitting older age.

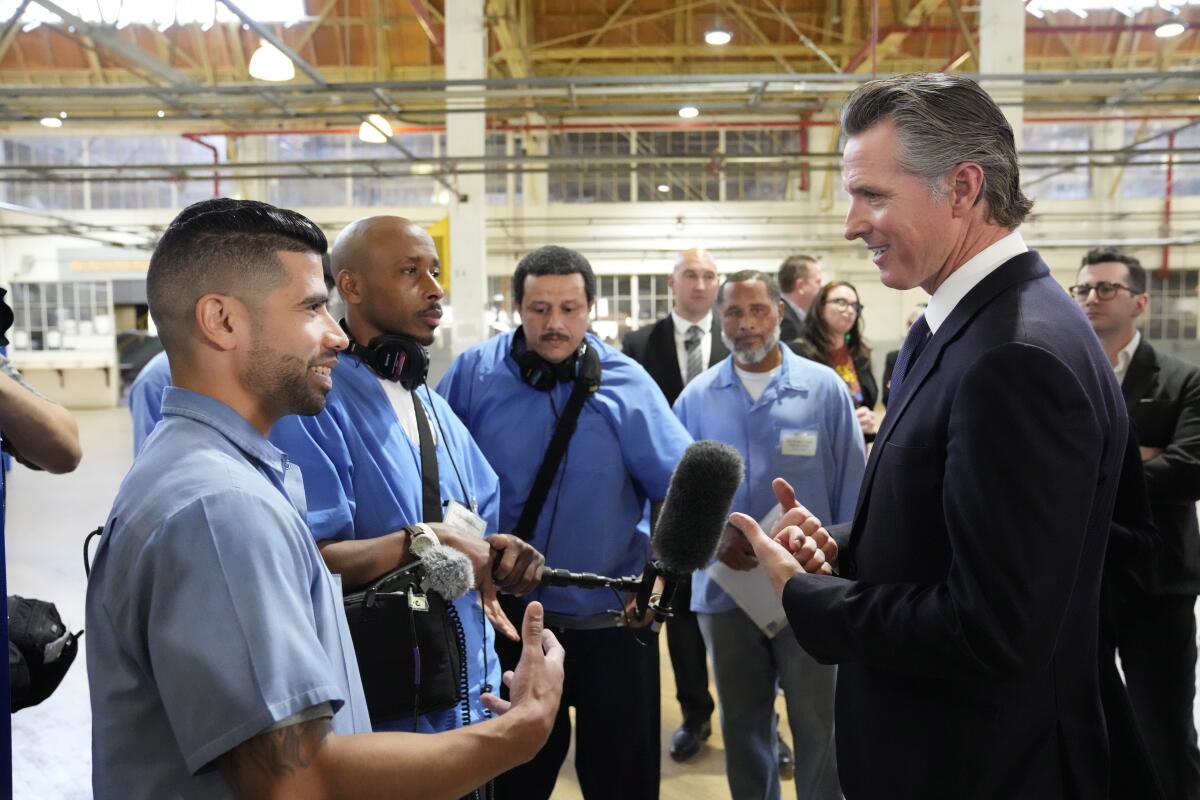

COVID “accelerated the consciousness” of the plight of California’s ailing and aging prisoners, Newsom told The Times in an interview last month, in which he described meticulously poring over scores of clemency applications.

“They’re 80, 90 years old. … You have deep empathy and you’re like, ‘this is crazy,’” Newsom said. “And then you read their record and you’re like ‘whoa.’”

Though Newsom has closed two prisons, enacted a new focus on rehabilitation at San Quentin and halted death row executions, he is acutely aware of the political risks involved in wading into the judicial system to free people convicted of crimes.

Newsom will be forced out of the governor’s office by term limits in early 2027 and is widely considered a potential presidential candidate in 2028. He’s mindful that he’ll be blamed for the misdeeds of any prisoners he releases.

“It’s tough. It’s your name affixed to it. ... I mean literally you’re accountable for whatever those decisions are,” Newsom said. “It’s a deep responsibility. I have to think about the victims. I have to think about precedent.”

Moreland still struggles with shortness of breath and dizziness after long COVID, and takes blood thinners to prevent further blood clots. He works full time as an ambassador for L.A. Metro, assisting public transit riders.

On the weekends, he relaxes with his wife, Sherry, listening to Loretta Lynn and Sam Cooke records, and tries to make it to local jazz concerts.

In 2002, he was sentenced to 33 years-to-life in prison for carjacking and kidnapping to commit robbery — a crime he says he was wrongly accused of. According to court records, he and another man were convicted of holding a driver at gunpoint after a traffic accident and demanding that he pay for vehicle damage caused by the wreck. The victim said the men threatened to shoot him, and ultimately dropped him off at his home but stole his van.

It was not Moreland’s first run-in with police: He had been in prison before for drug possession and vehicle theft charges — crimes he said he committed while in the throes of a heroin addiction.

“When you are a heroin user and you don’t have heroin, you get sick, your body craves it. So, I was doing the crimes to go get drugs in order to, as insane as this sounds ... I had to put something in my system in order just to be normal,” he said.

His long sentence for the burglary allegation included charges for ransom and making a terrorist threat, plus enhancements for use of a firearm and committing a felony with a prior prison term, records show. He maintains he was misidentified in a police lineup and had never seen the victim before “in my life.”

During his decades in prison, Moreland acted as a mentor, leading rehabilitative programs to help people reflect on their lives and choices. He still mentors people in prison, and works with a church to help those who have also recently been granted freedom.

Although Newsom’s medical reprieves affect just a tiny fraction of California’s prison population, they represent what advocates have long called for as the incarcerated get older: the opportunity for release for those who are struggling with health issues but aren’t necessarily incapacitated or near death.

Medical reprieve recipients include people in their 70s and 80s who use wheelchairs and have medical conditions that posed an “elevated risk for morbidity” during COVID. At least one grantee has died since being released, records show.

Thousands more inmates in addition to those medical reprieves were also released early at the peak of COVID to curb deaths as state prisons struggled to adequately respond to the rapidly spreading virus.

Heidi Rummel, a law professor at USC who heads the Post-Conviction Justice Project, said California considers factors such as age and health more than ever before when determining the opportunity for release, as research has shown those groups are significantly less likely to re-offend.

The state already has programs in place that allow people the opportunity for early release based on their age and health. Still, there’s a long way to go, Rummel said, and prisoners are often denied release in California despite those struggles.

“There may be some very sick people in prison who will never get out,” she said. “It’s good that [Newsom] is doing something, but it’s not a solution to the bigger problem. The aging prison population and the people trying to survive in prison with dementia and chronic illness ... it’s really bad.”

In some cases, Newsom has released people during the pandemic against the wishes of his own parole board.

Last year, Robert Williams, 67, was nervous and out of breath as he stood across from parole officials and explained why he was late for his hearing.

He had ridden the city bus nearly an hour from the transitional housing center where he lives in Lawndale to his parole hearing in Compton, and had fallen out of his wheelchair in the rush to make it there, according to a parole hearing transcript obtained by The Times. Strangers stopped to help him up.

Williams was also wearing a knee brace — the day before, he had fallen down some steps using a walker, he said.

Parole Commissioner Catherine Purcell, a former judge and district attorney for Kern County appointed by Newsom, acknowledged in the hearing that Williams is “essentially disabled.”

He has undergone two heart surgeries and a kidney transplant, and struggles with diabetes, chronic viral illness and breathing, nerve numbness and mobility problems, according to parole records.

Williams served 45 years in prison for murder and robbery charges, crimes he repeatedly denied in his latest parole hearing, one of many times he had sought and been denied parole.

He was 19 years old and a heroin addict when he and three co-defendants were convicted of stabbing and killing a 66-year-old woman after breaking into her home and robbing her in 1977, according to parole records. The four were also charged with robbing a man and beating him with a tire iron in 1976.

Despite Williams’ medical problems, the parole board ruled that he still posed a risk to public safety, and denied him parole last year.

“You were able to get to the bus, you’re able to function,” Purcell told him, according to a transcript of the hearing. “The report says you go to the food bank by yourself. Clearly, you are capable of engaging still in violence or in threatening someone or harming someone.”

But Williams was already living free under Newsom’s medical reprieve. The parole board’s judgment means Williams is still technically in state custody and required to wear an electronic ankle monitor.

He could be sent back to prison and his reprieve “may be nullified at any time for any reason,” Newsom wrote in his decision.

As governor, Newsom has granted more than 300 pardons, commutations and reprieves through a system that involves multiple layers of scrutiny.

His predecessor, Gov. Jerry Brown, also used his clemency power to free hundreds of prisoners and pardon more than 1,000 people. But most prior governors barely used their clemency power at all. Newsom said he understands why.

“They never wanted to be accountable,” he said.

Newsom said the decisions are made with extreme vetting by a team dedicated to clemency applications that he also examines himself. His critics “on the sidelines” don’t understand his position, the governor said.

“The minute there’s one mistake ... then the entire process is reevaluated in a way that actually can do more harm to people than good,” Newsom said, warning that if someone released on his watch were to re-offend, it could set back the prison reform movement.

Emily Harris, co-director of the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, said the pandemic “showed us that we can decarcerate quickly and safely,” and is proof that more can and should be done.

“We tend to think about this issue with exceptionalism, by picking a handful of people, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. We should be doing much broader swaths of the population,” Harris said.

As part of the federal coronavirus relief plan, thousands of prisoners across the country were also released, allowing them extended home confinement instead. Three years later, only 22 of the more than 13,000 people released under the program have been rearrested, and most for minor offenses, according to an analysis released by Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), who supported the policy.

But some critics are worried that the pandemic has been wrongly used to justify mass prison releases.

In November, Riverside County Dist. Atty. Mike Hestrin objected to the early release of a 67-year-old convicted of raping a child in 1994, who is eligible for a state program that offers leniency based on age and diminished physical condition.

Hestrin has urged Newsom to reconsider the release in that case, and said that people can “still be a threat to the public” despite medical conditions or older age.

“We have to remember there’s another party involved in these crimes and that’s the victims,” Hestrin said. “Certainly there are crimes that don’t require great physical prowess.”

Lynn Beyett, too, thought he would die in prison.

The first time the 71-year-old was incarcerated, he was only 12 years old. He had fled his father’s relentless beatings the year before, and wound up “raising myself” on the streets, he said, learning how to steal to survive.

An addiction to heroin and eventually meth landed him several more stints in prison as an adult, mostly due to thefts to pay for his habit. Altogether, he has spent more than half of his life in a prison cell.

Before he was convicted of burglary in 1998, Beyett said he had been “on a binge,” awake for weeks and high on meth when he broke into a wealthy former client’s house in search of cash. He doesn’t remember stealing the homeowner’s purse or threatening to kill her if she called the cops, which she accused him of, according to parole records.

“Meth took my life. There wasn’t a second I wasn’t stealing or plotting to steal,” Beyett said, sitting at the flooring warehouse where he now works in Sonora, sleeves of faded tattoos poking through a Star Wars T-shirt that reads “best dad in the galaxy,” a gift from his daughter.

In 2020, he was granted a medical reprieve by Newsom. Beyett had applied for clemency for years and participated in rehabilitation programs, where he learned about his triggers and reconciled the mental health impacts of his childhood trauma.

He forgave his dad, who died years ago, for the abuse, and has sought forgiveness from those he has stolen from, whose sense of security he says he knows he rattled.

Now, he spends his free time hanging out with his grandchildren and fishing and panning for gold in the creeks of Tuolumne County. He plans to get married next year after meeting his fiancee through her prison ministry work.

Mostly, though, Beyett, works, trying to make up for the financial setbacks that come with decades in prison. Even as he is “full of osteoarthritis” and bone spurs that make installing floors especially difficult, he works through the pain, thankful for the income and for an employer willing to see past his criminal record.

“I can barely walk at the end of every day,” said Beyett, who recently underwent knee replacement surgery but said he refuses pain medication because of his addiction history.

Beyett feels “totally blessed” and said that he spends every day doing the best he can for everyone in his life. But he felt singed by Newsom’s letter of reprieve when he read it.

In each of his clemency grants, Newsom’s caution is reflected in his language, saying that it “does not minimize or forgive” their conduct “or the harm it caused.”

At first Beyett was surprised by Newsom’s refusal to forgive him. But after some reflection, he said it made sense.

“He was trying to wash his hands of me if I came out here and did something wrong,” Beyett said. “But I’m doing so good out here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.