- Share via

She was 15. He told her he was 17, just a few months shy of 18. They met on Instagram during the summer of 2022.

The girl, who lived with her mother, younger sister and grandparents in Riverside, kept their “relationship” a secret from her family. They would send messages through Instagram and talk over Discord, an instant messaging platform that allows voice calls.

He showered her with gifts, sending her jewelry, groceries, money and gift cards. He paid for her UberEats and DoorDash deliveries and helped her buy birthday gifts for her friends, telling her he had a good job that could pay for it.

But then he got clingy — pushy, even. He was pressuring her to send nude photos, which made her uncomfortable. Right after Halloween, she broke up with him.

She blocked him on Instagram, but he still found a way to send her a suicide letter.

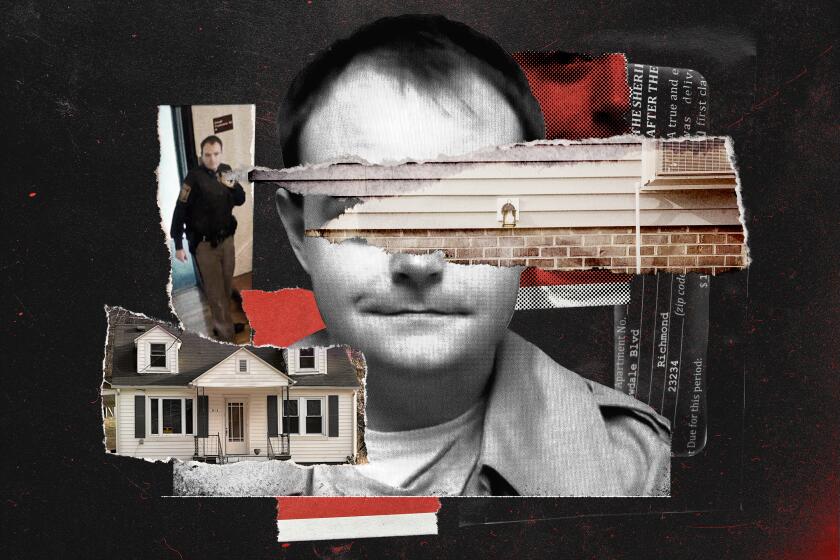

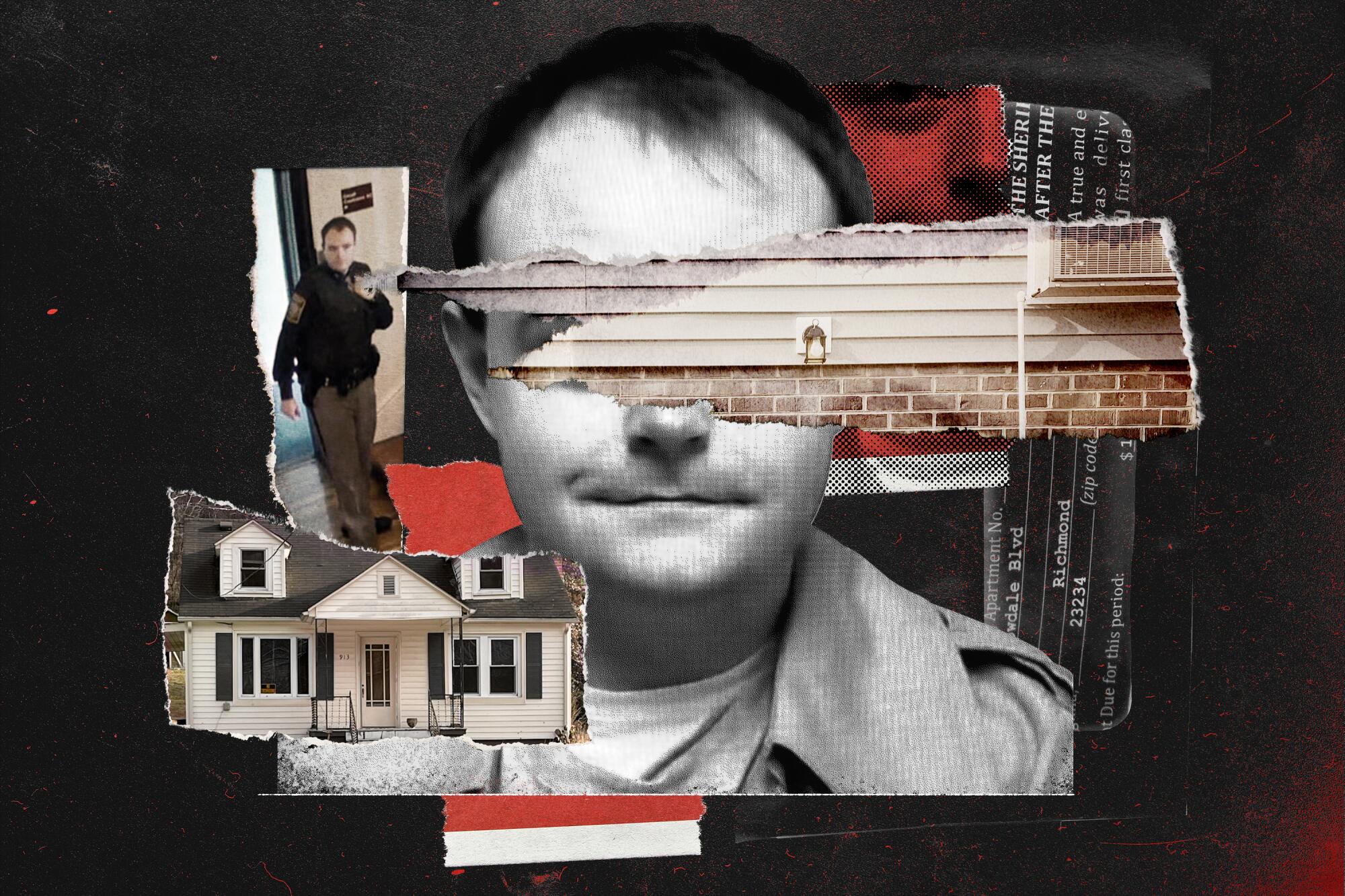

Virginia cop Austin Lee Edwards ‘catfished’ a Riverside teenager online, killed three of her relatives and set her house on fire in November 2022.

In reality, the “boy” she had been talking to was a 28-year-old sheriff’s deputy from Virginia named Austin Lee Edwards. And on Black Friday, a few weeks after the teen broke up with him, he drove to her home in Riverside and killed her mother, Brooke Winek, 38, and her grandparents, Mark Winek, 69, and Sharie Winek, 65. He set fire to their house before kidnapping the teen at gunpoint. After getting into a shootout with police, Edwards shot himself with his service weapon and died, according to police. The teen was physically unharmed.

New, grisly details about the incident are now coming to light through a federal lawsuit that the now-16-year-old and her foster mother filed Friday against Edwards’ estate; the Washington County Sheriff’s Office in Virginia, which employed him at the time of the killings; Washington County Sheriff Blake Andis; and Det. William Smarr, the investigator who reviewed Edwards’ employment application at the agency.

The lawsuit alleges violation of her 4th Amendment rights, false imprisonment, negligent hiring, assault and battery, among other charges. Scott Perry, the teen’s attorney, said the damages amount to at least $50 million.

The filing is the second suit by a member of the Winek family against the Sheriff’s office — Mychelle Blandin, Mark and Sharie Winek’s surviving daughter, filed a lawsuit last year, alleging negligent hiring practices and seeking more than $100 million in damages. The lawsuits hinge in part on reporting by The Times that detailed how police hired Edwards despite his troubling mental health history.

In February 2016, Edwards was detained by Abingdon police in Virginia after he cut himself and threatened to kill himself and his father, who told police the incident was spurred by Edwards’ problems with his girlfriend, The Times reported. The incident prompted two custody orders, Edwards’ stay at a psychiatric facility and a court’s revocation of his gun rights, which were never restored.

Perry is arguing that Edwards should never have been hired and that the sheriff’s office failed to interview most of Edwards’ references or conduct a proper background check. If they had, they would have discovered the mental health orders, the lawsuit claims.

“The Washington County’s Sheriff’s office gave Austin Lee Edwards a gun, a badge and cloaked him with the authority of the law,” Perry said in a statement. “He used these things to gain access to the Winek home and commit these atrocities. We will prove that an adequate investigation of Edwards’ background would have prevented this tragedy.”

The teenager and her foster parent declined interviews for this story. The Washington County Sheriff’s office didn’t respond to requests for comment.

According to The Times’ review of Edwards’ personnel file, which includes his employment application, Smarr chose not to interview Edwards’ father, who was listed as a reference, because of their “close familial relationship,” the detective wrote. Smarr spoke with Edwards’ previous employer at Lowe’s, but he couldn’t get hold of two of Edwards’ personal references or his two neighbors.

Austin Lee Edwards said he checked into a mental health hospital in 2016. Further inquiry might have kept him from becoming an officer, a police official said.

Smarr also sought background information from the Virginia State Police, where Edwards had been employed for nine months before resigning and applying to Washington County. But Smarr was rebuffed by a sergeant there, who said he wasn’t comfortable answering whether Edwards had gotten in any trouble, been reprimanded or been subjected to an internal investigation.

In addition to Smarr, the lieutenant and captain of the Washington County Sheriff’s criminal investigation division signed off on Edwards’ employment application, as did its personnel director and chief deputy, according to the file.

“Edwards has no criminal history or civil issues, past and current employers speak positively of him, as well as his references,” Smarr wrote. “It is my belief that Edwards is hirable.”

The most recent lawsuit also answers some lingering questions about the crime, including how Edwards met the teenager, why he decided to kill her family, and where he planned to take the teen after kidnapping her. Here is an account of what transpired during that fateful Thanksgiving holiday weekend, taken from the lawsuit and previous reporting by The Times.

The teenager celebrated Thanksgiving 2022 with her mother, her younger sister and her mother’s boyfriend at Golden Corral. Afterward, they went to the Moreno Valley apartment where her mother’s boyfriend lived and stayed there overnight.

The next day, Brooke Winek and her daughters went to Starbucks, planning to go Black Friday shopping with Brooke’s boyfriend. When they got back to the apartment, Brooke got a call from her mother, Sharie, who told her to take the call off speakerphone because they needed to speak about something serious.

The Times reported last year that Edwards gained access to Sharie and Mark Winek’s home on Price Court by pretending he was a detective conducting an investigation involving the teenager. After getting into the Wineks’ home, Edwards told Sharie to call Brooke and tell her that she and the teenager needed to come to the house so he could ask them some questions.

In order to keep the “investigation” from her daughters, Brooke told them there was something wrong with their phones and that they needed to go back to their home on Price Court to get them fixed. Brooke then dropped off her younger daughter with Brooke’s sister, Blandin, before heading over to Price Court.

The teen recalled that, once they got to the house, Brooke put her keys in her purse and told her to wait in the car while she went inside. The teen noticed that she didn’t see her mother’s dog in the window, which was unusual because the dog always perched there whenever people visited the home.

After waiting for a while, the teen decided to go into the house. As she opened the screen door, Edwards grabbed her by the hair and pulled her inside.

Virginia cop Austin Lee Edwards spoke to Mychelle Blandin the day he killed her sister and parents, kidnapped her niece and burned down their Riverside home, Blandin told The Times in an interview.

In the moment, she thought the man grabbing her was the telephone repairman. She didn’t realize it was the man who had catfished her.

Then she saw the bodies of her grandmother near the entryway, her grandfather next to the stairs and her mother lying on the hardwood floor. She saw the bags over their heads, taped to their necks. Their arms and legs were bound with duct tape.

The teen started to scream.

Edwards was wearing a gold police badge on his belt in the shape of a star. As she yelled, he pointed a handgun, which also had a star engraved on it, at her.

“Stop screaming,” he said.

She recognized his voice. It was the “boy” she had met online, whom she had been talking to for months.

“Are you going to hurt me?” she asked.

“I will if you keep screaming,” he replied.

Edwards grabbed the teen and pulled her through the house, dousing everything with gasoline from a canister he brought with him and lighting the rooms on fire. He also opened the windows and doors so the flames would spread. Then he took the girl outside and forced her into the backseat of his red Kia Soul.

Meanwhile, the Wineks’ next-door neighbor saw the house on fire and called 911. Another neighbor, whose driveway Edwards had parked in, also called the police. She phoned the authorities again when she saw Edwards force the teen into his car.

After speeding away, Edwards told the teen to pretend that she was his daughter if anyone asked. He said he was going to take her back to Virginia. When the girl asked why he killed her family, he said that if he didn’t, they would “report it” and he wouldn’t have enough time to escape.

Years before the Riverside killings, ‘catfish’ cop Austin Lee Edwards groomed, stalked and solicited nude pictures from a teen girl.

Edwards also said he was a police officer and that agencies “need to do better backgrounds” because he “lied” during the hiring process. As he continued to drive toward his eventual destination of Saltville, Va., where he had recently purchased a home and blacked out the windows, he kept his hand on his gun. In the car with them was also the large, bloody knife he used to stab Brooke.

They made two pitstops during the drive to use the restroom, but Edwards never let go of the teen’s hand. They also made a stop so Edwards could clean the blood off himself. He told the girl that they wouldn’t stop for food until they left California and that they would drive to Virginia through Las Vegas, New Mexico and Texas. She would have to stay in the backseat, he said, until they got her a change of clothes.

The Riverside Police Department identified Edwards through interviews with neighbors, who provided descriptions of his car and video footage from security cameras. Police determined that he was in the Mojave Desert and alerted San Bernardino County authorities, who chased after his Kia Soul.

During the pursuit, Edwards fired his gun through the back window of the car, causing the Kia to fill with smoke. The fuel canister, which Edwards had placed in the backseat with the teen, splashed her with gasoline.

Edwards’ Kia drifted off the road and got stuck on some rocks under a bridge, enabling the police cars to catch up.

As law enforcement closed in, Edwards told the teen to get out of the car.

With nowhere else left to go, he turned his service weapon on himself and pulled the trigger.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.