Malibu’s homeless numbers are down nearly 80% from 2020, city announces

- Share via

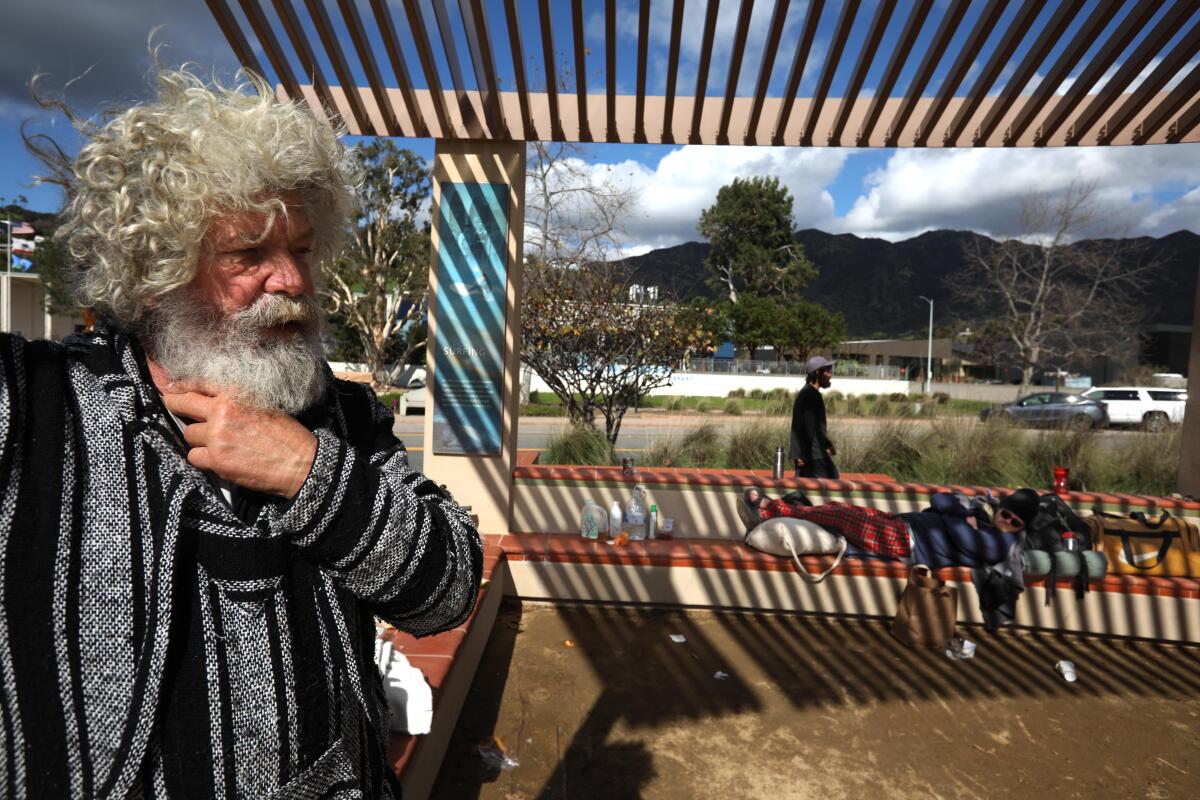

A few days after a yearlong stint at a sober living home in Los Angeles, Kacy Richardson finished a sandwich and stared at the gray clouds cruising over the green slopes of the Santa Monica Mountains. He was happy to be back in Malibu.

Richardson, 33, said he’s lived outdoors in the wealthy beach town for much of the past 10 years because it’s peaceful and people are kinder than those in Los Angeles or Santa Monica.

Like several of his companions in Legacy Park, Richardson has some complaints about the treatment of homeless people by sheriff’s deputies. But over the past two years, he said, he has seen increased efforts by the city to move people into shelters or permanent housing, including two friends who lived outdoors in Malibu for many years and now have apartments.

“It feels like the process is faster,” he said. “I’ve definitely seen more people being placed in apartments.”

City officials agree and are promoting statistics to back up the claim.

In an early release of its annual homeless count, Malibu announced a fourth straight year of declining encampments on its streets and beaches.

The team surveying Malibu as part of the annual countywide point-in-time count found 51 people living outdoors in January, compared with 71 in 2023 and 239 at the peak in 2020.

Two fires were caused by homeless people last year, the report said, a dramatic decline from the 23 in 2021. There were four in 2022.

An affordable housing shortage has stymied efforts to get people off the streets. The dismal state of SROs leaves L.A.’s poorest with even fewer places to go.

The results reflect Malibu’s proactive approach combining contracted outreach with enforcement by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, said Luis Flores, the city’s public safety liaison.

Flores said Malibu is showcasing its preliminary numbers months ahead of the official countywide release “to be proactive with our messaging.” Over the years, he said, there’s been an ebb and flow that creates “a perception that not a lot is being done and that we have a major crisis on our hands. We want to ensure and highlight that a lot of great work is being done.”

The city’s preliminary numbers may change slightly in the official count, which is generally not released until late spring or early summer. That’s because statisticians contracted by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority will adjust for the average number of people estimated to live in cars, vans, tents and makeshift shelters observed over the three days of the count.

Flores said he doesn’t expect the adjustment to be significant because the city’s count was conducted by skilled volunteers and outreach workers who are familiar with the local homeless population.

Since 2017, Malibu has contracted with the People Concern for services and currently has two outreach workers and a housing navigator, Flores said.

In Legacy Park, Richardson’s hangout, he and his companions said they have seen the difference. But they fault the city for not having a shelter or affordable housing. At night they move across the street to the library, adjacent to the courthouse. The buildings provide protection from cold winds, and the awnings keep them dry from rain.

“There’s a lot of towns that have to build housing for low-income people, but Malibu has zero,” said Elvin Dekle, pushing his belongings into the park in a shopping cart one recent afternoon.

Dekle, 69, said he has been living in Malibu for 20 years. He acknowledged an improvement in services but wonders why the city doesn’t use vacant land near Pepperdine University to build housing or, at least, establish a place where people can sleep.

The City Council rejected a 2022 recommendation by its task force on homelessness to provide funds to create interim housing outside the city limits. Instead, the city funds for four shelter beds in Santa Monica, Flores said.

Dekle’s friend Kenneth Erickson agreed that a designated sleeping space would be helpful, especially since he is not ready to live indoors, paying rent and other bills.

Erickson, 38, a former pyrotechnic artist for music concerts, said he came to Malibu after spiraling into homelessness eight years ago, because it felt safe.

“The area is peaceful,” he said. “You don’t have to worry about people robbing you or hurting you while you’re sleeping.”

While he appreciates that the city is trying to get people indoors, he thinks it is moving those who are not mentally ready and need more guidance to prepare them for the responsibilities that come with housing.

According to monthly outcome records posted on the city’s homelessness website, the People Concern outreach workers made more than 3,900 contacts last year, with a monthly average of 72 individuals. Over the year, the team moved 51 people off the streets: 28 went into shelters, 15 went to permanent housing, and eight relocated to live with family or friends elsewhere. Another 14 have vouchers and are searching for housing.

The monthly reports indicated that 100 new homeless individuals had been identified during the year. With the decline of 20 in the overall count and 51 moved from the street, there are dozens unaccounted for.

It’s not uncommon, Flores said, for people to show up in the city, hang around for a day or two, then leave, especially near the end of the Metro bus line that runs from Santa Monica to Trancas Canyon.

“We see faces on a routine basis, and we never see them the following day or the following week,” he said.

A Malibu ordinance prohibits overnight stays “in any public park, public beach or public street (including in a vehicle parked on a public street).” An amendment bringing the law into compliance with federal court rulings specifies that it will not be enforced on people who “do not have access to adequate temporary shelter.”

The city’s removal program cleared 29 encampments in 2023, half as many as it did in 2021, reflecting the decline in the overall homeless numbers. Outreach workers provide advance notice of encampment removals and offer services and shelter, Flores said. Sites are revisited to ensure that no campers return.

Flores attributed the decrease in fires to an aggressive media campaign and enforcement. Signs have been posted in canyons and parks warning people not to start fires. Also, the Sheriff’s Department identified and arrested people who were known to start fires, Flores said; others got housed or simply left.

Sheriff’s Sgt. Chris Soderlund reported that eight of the city’s 11 arson arrests since 2020 involved homeless people.

“Once one individual gets arrested and charged, we use outreach and the Sheriff’s Department to push that,” he said. “The message spreads. A lot of individuals who started fires are no longer here.”

After a decade on and off Malibu’s streets, Richardson hopes to get on a housing list, “because being out here sucks,” he said.

Though it’s relatively safe, and people are kind, he sometimes feels hassled by deputies who tell him where he can and cannot linger.

His main complaint is being cited for taking shopping carts from Malibu Village, a shopping center lined with restaurants and boutiques.

“We have nowhere to put our stuff and no way to transport it,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.